An expert in classical rhetoric analyzes Trump

I’m a classics professor who researches the rhetoric of the Roman orator Cicero. Cicero lived from 106 to 43 BCE – he died a year after…

I’m a classics professor who researches the rhetoric of the Roman orator Cicero. Cicero lived from 106 to 43 BCE – he died a year after Julius Caesar and knew him well. He was executed on the order of Mark Antony, who had his head and hands nailed to the speaker’s platform in the Roman forum after his death, because he’d delivered a series of speeches attacking Antony the year before. Cicero published about 100 speeches – some from court trials, some from the senate, and some delivered to the people – during his lifetime, and we have 58 surviving today because they’ve been studied by scholars and schoolchildren as models of eloquence since antiquity.

As it turns out, political rhetoric doesn’t change much over time, even over 2,000 years. Just like today’s orations, Cicero’s speeches have an introduction (exordium) and conclusion (peroratio). He uses a combination of logic, authority, and emotion (logos, ethos, and pathos in Greek) to sway his audiences. He can switch from powerful, almost poetic language worthy of great moments in history to a plain, conversational style and back again, when he thinks the moment calls for it.

Rhetorical devices like the ones Trump uses, the same ones Cicero used, aren’t just good material for high school English exams. They affect the way we respond unconsciously to oratory. Persuasion, as Cicero recognized, isn’t just a matter of logic; humans aren’t very logical creatures, after all. It’s a matter of feeling.

So how does Donald Trump measure up against Cicero?

If Cicero gave the kind of extemporaneous, unscripted speeches for which Trump is best known, we don’t have any evidence of it. Even before the age of Twitter, Cicero was famous for his quips and one-liners, which were collected by his fans after his death.

When Donald Trump gave an unusually elaborate scripted speech to Congress, he gave us a chance to analyze his rhetoric more closely. The description of this speech as “presidential” is a good example of persuasion by ethos, i.e. authority or “character.” Trump sounded like the right kind of speaker (more or less), and so his speech was, by that metric, a success.

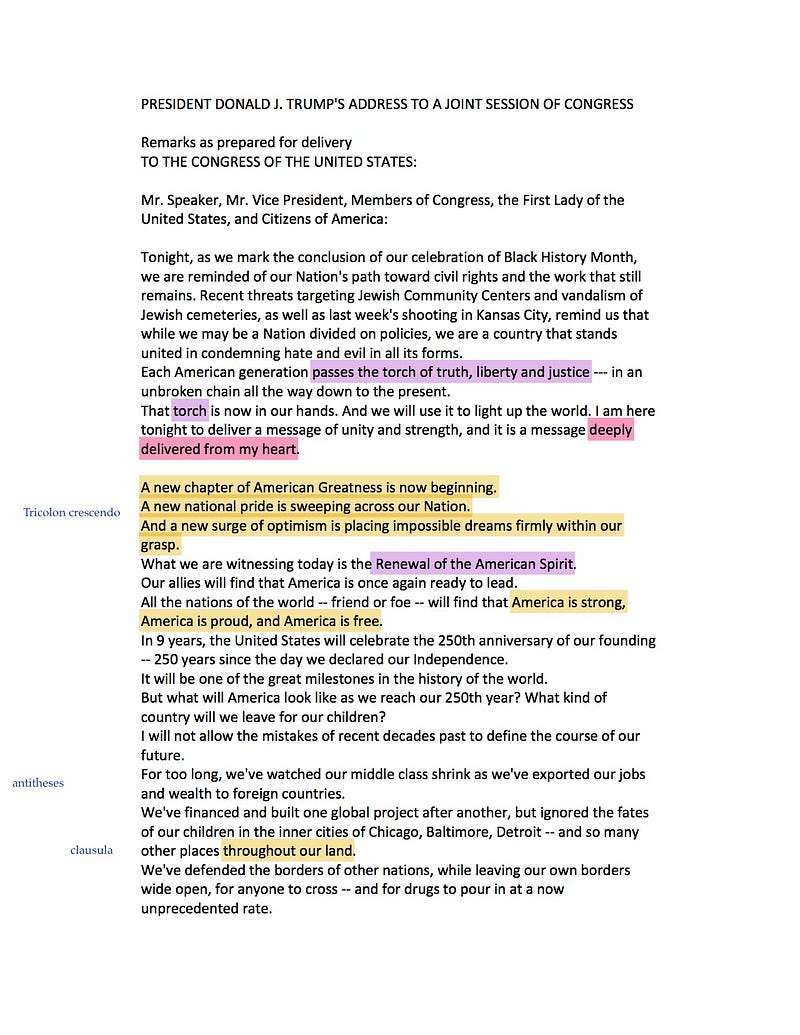

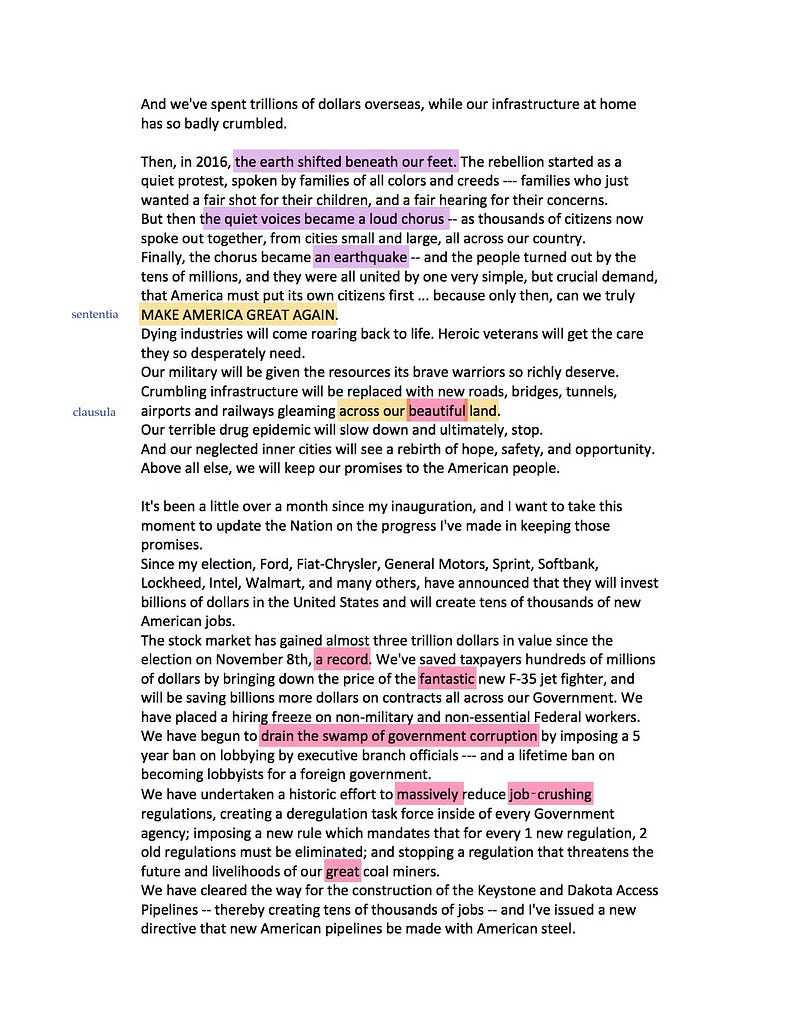

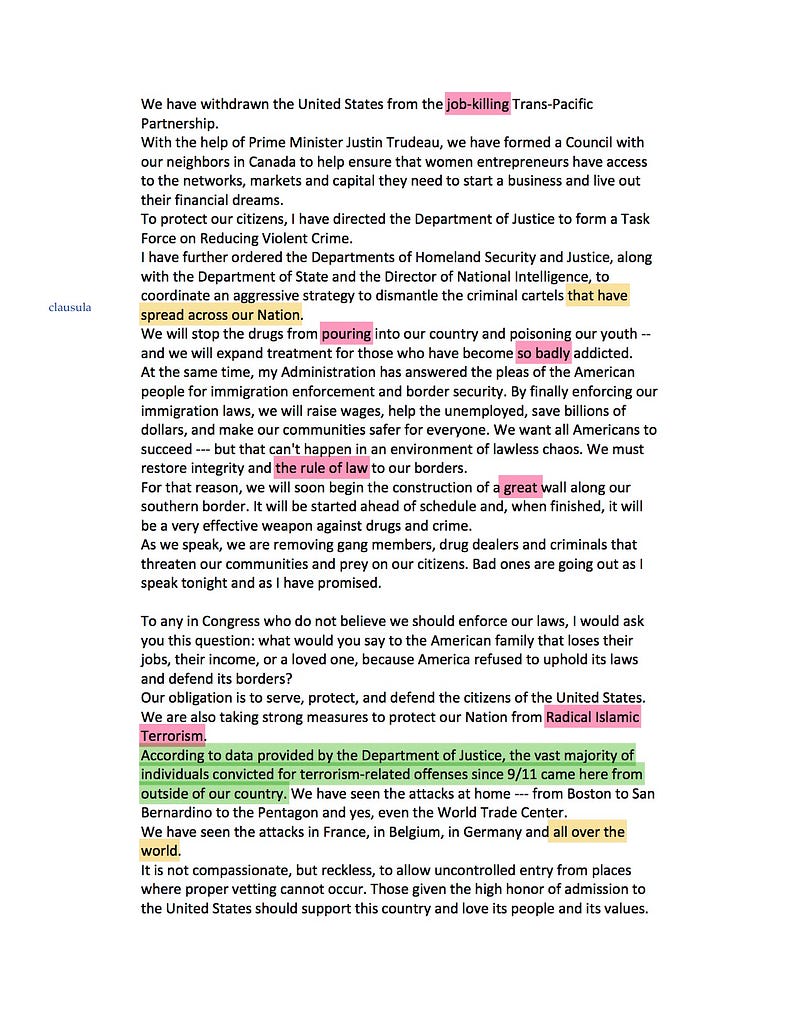

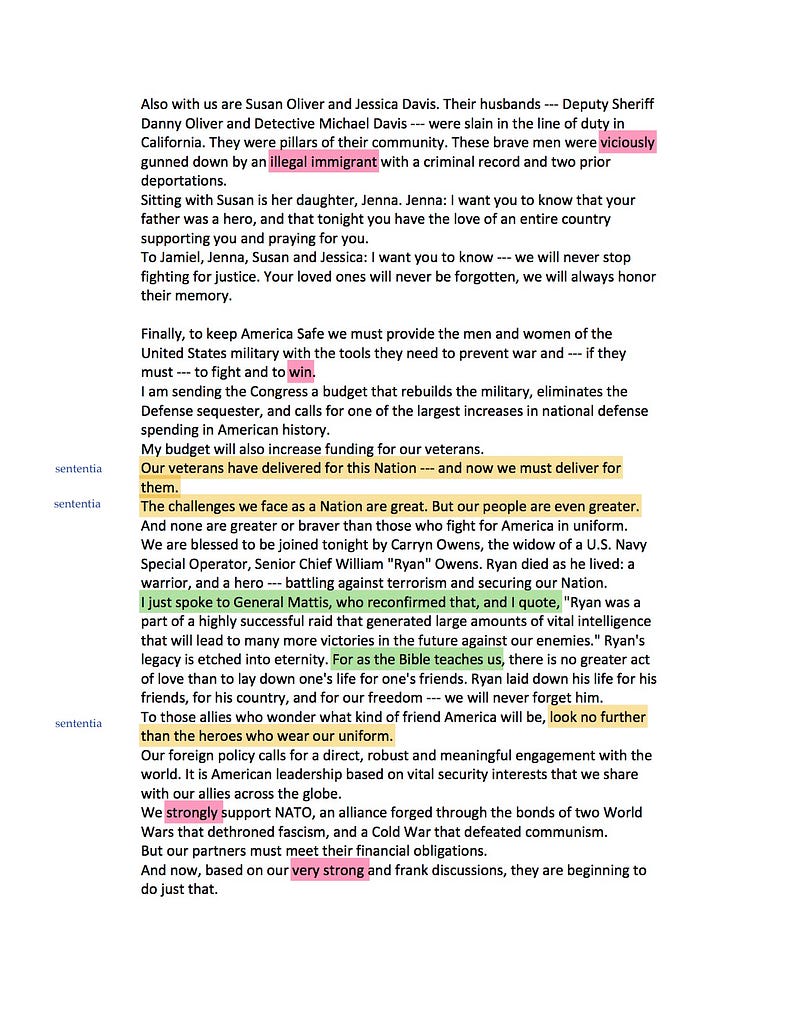

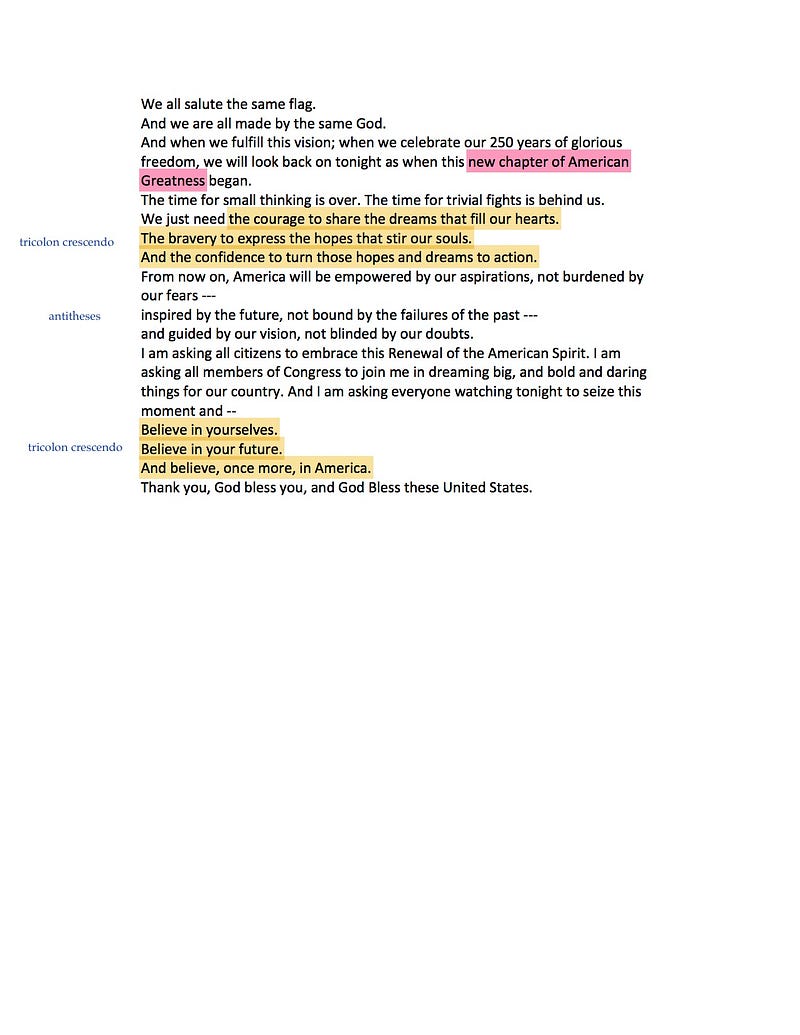

Like most orators, Trump sprinkled his oration with rhetorical figures (highlighted in yellow). One common figure in political orations is the antithesis, a pairing of two contrasting ideas in similar language: “Our veterans have delivered for this nation, and now we must deliver for them,” for example. It shows the orator’s wit when he can connect disparate ideas in this way. Trump uses a tricolon crescendo six times (actually, one of them is a tetracolon), a figure in which the orator lines up three similar phrases or clauses in order from shortest to longest: “America is strong, America is proud, andAmerica is free.” Often, the tricolon also features asyndeton – a conjuction like “and” is left out, for poetic effect. He uses plenty of sententiae, memorable turns of phrase, the ancient equivalent of a soundbyte. He concludes many of his sentences with common, formulaic, literary phrases. Referring to places “throughout our land” instead of “everywhere” is more flowery than your typical everyday Donald, and builds a sense of occasion through elevated language.

The yellow highlights are clustered densely in Trump’s introduction and conclusion, which Cicero would have agreed is the right place for grand, inspiring language. They virtually disappear in Trump’s narration of his first weeks in office, as he transitions to a lower register. That’s where we start to get more pink highlights, or “Trump-isms.” Trump’s style is marked by his use of adverbs and adjectives – his favorites are “great,” “beautiful,” and “incredible” (and, of course, the oft-misinterpreted “big-league,” which was apparently too colloquial for this occasion). He saves his trademark vocabulary

for his favorite topics: trade policy reform and victims of illegal immigration. There are many more Trump-isms in transcripts of the speech as delivered, but this is the script as prepared – this seemed fair, since Cicero would (we assume) have edited his speeches for publication too. As Trump transitions to a section of the speech outlining his proposals for the future, the yellow highlights (rhetorical figures) return: he’s elevating his language again to maximize the inspirational force of his vision.

In green are passages where Trump cites evidence or sources for his claims. There are already plenty of analyses of the factual accuracy of Trump’s claims in the speech, so I leave you to read any of your choosing, but it’s worth thinking about where Trump bothers to cite his sources and why. The category of “individuals convicted for terrorism-related offenses since 9/11” is so specific as to be virtually meaningless, but Trump cites it anyway as material evidence that Radical Islamic Terrorism is a material threat – in Congress, that’s a (justly) controversial claim. The citation of two Republican presidents connects Trump to his own putative party, a relationship which has been shaky at best. Many of Trump’s citations and figures have to do with money, implicitly reminding his audience of his self-identification as a businessman first and politician second. He presents his proposals as financially logical, while his appeals to ideological principles strengthen his supporters’ commitment on an emotional level as well. Finally, he quotes the Bible to glorify the death of Navy Seal Ryan Owens, killed in a raid gone wrong in Yemen: this religious idealization of self-sacrifice romanticizes a tragic and possibly needless death.

Finally, no rhetorical analysis would be complete without some discussion of logical fallacies. A “straw man,” an imaginary opponent, makes an appearance when Trump addresses “any in Congress who do not believe we should enforce our laws” (surely not a common belief among legislators). Trump prepares his supporters to celebrate that his “great wall” “will be started ahead of schedule,” which leads critical readers to wonder: if you’re the one setting that schedule, doesn’t that mean the wall will be started on time? Or did you schedule it to start late, just to be able to make this claim?

There’s one conspicuous omission from Trump’s rhetoric here. Cicero tells us that when you’re starting a speech, your first task is to make sure that your audience likes you enough to listen to what you have to say, through a captatio benevolentiae, or a “capturing of goodwill.” Trump does call for bipartisan cooperation later in the speech, but in an oration addressing the Houses of Congress, Cicero would have told him to start with that. Instead, Trump’s reference to Black History Month is a good place to start, but his claim that “we are a country that stands united in condemning hate and evil in all its forms” falls short of what Cicero advised. In fact, as many commentators noted, it detracted goodwill instead of capturing it: it reminded many of Trump’s detractors that he has failed to condemn hate and evil in the form of anti-Semitism on several recent occasions. Trump has never been a unifying figure, but perhaps next time, he’ll take a page from Cicero’s playbook.