Education and democracy

Aristotle described a broad education as one of the distinguishing characteristics of a free person but also of a free and independent mind, hence “liberal" education. Citizens in a democracy need education to free their mind.

What do we lose, if we lose liberal arts education?

I've been reading that higher education is under attack for most of my life, but the attacks used to be slower-moving and less overtly malicious. As much as possible, I'm finding comfort in the knowledge that repression of liberal arts education is nothing new, and that this kind of repression has been resisted successfully before.

I took education for granted when I was a student, to be frank, and rarely gave much thought to its value or what I wanted to get out of it. When I became a professor, most of my students saw higher ed merely as a set of hoops to jump through on the way to a career. (I don't mean to blame them for this, because this is a common view among their parents and among mainstream media sources.) Not many students thought about it as a transformative or liberatory intellectual experience. And cost was a significant obstacle, to be sure, but higher ed was a commodity widely available, certainly not illegal or banned.

At the University of New Hampshire, I created and taught a class that I called “Athens, Rome, and the Birth of the USA.” I’d spend the first third of the semester teaching the history of Athenian democracy and the Roman republic. We then connected what we learned to how American thinkers like Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton cited Athens and Rome as models for the American Revolution and for the United States. For the second third of the semester, we wrestled with the challenges of self-government that the founders tried to mitigate: factionalism, tyranny, domination by wealthy oligarchs, popular uprisings, and free speech.

Finally, at the end of the semester, we looked at how the founders of the USA appealed to Athens and Rome to legitimize cultural institutions and practices, including enslavement, the exclusion of women from government, and liberal arts education.

That session on liberal arts education was always a wild time. It began, inevitably, with twenty minutes of ranting by my students about general education requirements as a detour from their career goals. Once we’d aired our grievances, I would ask: "What comes to mind when you picture an 'educated person,' and what kinds of things does that person know?" Students answered: current events, world cultures and geography, science, literature…they frowned as they started listing areas of knowledge that sounded suspiciously similar to their gen ed requirements.

In classical Athens, rhetoric teachers recommended that aspiring lawyers and political leaders study a wide range of human knowledge – that is, a paideia (education) that was encyclic (“full circle” or general), hence our modern word “encyclopedia.” Armed with diverse kinds of knowledge in this way, you’d be prepared to speak in a compelling, persuasive, authoritative way on any subject. In the Politics, Aristotle described this type of education as one of the distinguishing characteristics of a free person (i.e. not a slave) but also of a free and independent mind, hence “liberal” (from the Latin word for “free,” where we get our words “liberty,” “liberation,” etc.).

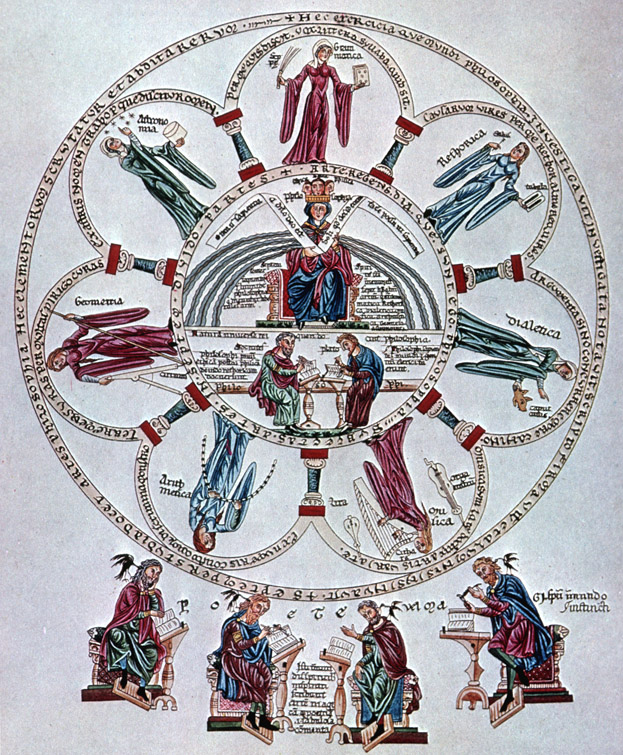

Roman authors like Cicero adopted the classical Greek concept of liberal education, and often actually studied rhetoric and philosophy in Greek cities. In Europe in the Middle Ages, following the same tradition, students began with the trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric, and advanced students then moved on to the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy (all studied in Latin).

However, the thing to remember about all this, I told my students, is that probably none of us in that classroom would have had access to this kind of education in antiquity. Many of us probably would have been illiterate.

In antiquity, education beyond the basic was for wealthy people with money to spend on books (all written by hand) and time to spend on reading instead of manual labor. Roman women had more access to education than Greek women, in general, but only in wealthy families. Tradespeople like carpenters, masons, cooks, and artisans might know a lot, but according to Aristotle, their knowledge wasn’t “liberal” in the sense that it didn’t particularly liberate their minds or enable them to think independently.

Aristotle advised leaders in democratic states to ensure that their citizens got this kind of education. It was in the public interest to ensure that free citizens could act like free citizens, to conduct themselves properly with a democratic spirit, as befits free citizens – and so it was in the public interest to educate them to do just that.

The connection between liberal arts and liberation of the mind always seems particularly clear to me when I hear or read about humanities programs in prisons (I've heard talks on this subject by Nancy Rabinowitz and Emily Allen Hornblower, but there are many examples). Reading and discussing Greek tragedy or epic is a chance for people to reflect, critique, analyze, form opinions, and disagree freely. These are basic skills that liberal arts education should help us to develop. They are also the skills that free people have the power to use, and they are skills that our carceral system often denies people the opportunity or freedom to use. Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Black Panthers until he was killed by police in 1969, wrote that "you can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail the revolution;" many incarcerated activists of the 20th century gave themselves a broad and deep education in the liberal arts in prison libraries.

However, when Aristotle says that citizens in a democracy need a liberal education, he mostly seems to be thinking of wealthy, powerful citizens. If you’re born outside that class, he doesn't seem to think that you particularly need much liberal education, or that you'll be able to make much use of it or benefit much from it – and, in fact, it's a moot point because you cannot access it. As a result, you probably will not be able to speak in a persuasive, authoritative way in the public arena. You will not have the knowledge, the references, the cultural capital that members of the political class have, and your speech will always be different – not the kind people listen to. Athens might have been a democracy (although it wasn't by the time Aristotle was writing), but that definitely does not mean that all citizens had an equal voice or equal influence in politics.

American thinkers were deeply influenced by this classical tradition of liberal arts education. Thomas Jefferson, born a member of the wealthy upper class in Virginia, had the best liberal arts education available in the colonies in the classical tradition: personal tutors, a local school where he studied Greek and Latin, college at William and Mary, and studying for the bar. Like Aristotle, he saw this kind of education as essential in a self-governing state like the USA: “Every government degenerates when trusted to the rulers of the people alone. The people themselves therefore are its only safe depositories. And to render even them safe, their minds must be improved to a certain degree.”

Jefferson didn't believe in giving women, Black or indigenous people, or poor people access to higher education, any more than Aristotle did, and the U.S. went so far as to bar access to higher education entirely for those and other groups, but I'll save that for my next post.

Liberal arts education is liberating when students have the freedom to use new knowledge and rigorous ways of thinking to develop their own ideas, to challenge authority and entrenched ideology, and to understand the world better. (Sometimes they challenge each other and/or their teachers, which is unpleasant but healthy.) I think now is a good time for students to learn about and reflect on what has made liberal education worth fighting for, despite barriers based on class, gender, and race, and the walls around it worth climbing or breaking down.

Some discussion questions you might bring to students in the next few weeks or months:

- What does an "educated person" know? What makes you say that?

- Who do you picture, if I ask you to picture an "educated person"? Why?

- What kind of education would produce the best political leader?

- What kind of education does a person need, to be the best voter or citizen? What resources does a person need to get that education?

- How would you describe a "free mind" or a "free thinker"? What kind of education makes the best "free thinker"?

- In news or politics, when you think people are saying something untrue or misleading, what is the best way to educate yourself? What resources do you need? What are the limitations or disadvantages of those resources? Have you learned about new strategies or resources to educate yourself since you started college?

Further reading

W. Martin Bloomer. 2011. The School of Rome: Latin Studies and the Origins of Liberal Education. University of California Press.

Emily Hornblower did an event for the Philadelphia Ethical Society about her teaching in New Jersey prisons with a reading from Euripides' Medea and a conversation with Nafeesah Goldsmith, co-founder and COO of YFOF (Youth Function Over Form), which you can watch on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oNMucB3YxiQ&t=52s

Caroline Winterer. 2007. The mirror of antiquity: American women and the classical tradition, 1750-1900. Cornell University Press.

More Thomas Jefferson on liberal education, and how much classics is too much: