What makes teaching feminist?

The core principles of feminist pedagogy are radically inclusive and democratic: An insistence that education be applicable to real struggles to liberate; An effort to make classroom spaces more egalitarian or democratic; and The validation of lived experience as a source of knowledge

There are many different ways of defining feminism, and many different ways of being feminist, of embodying feminist principles and values in one's actions and choices. In the academy, feminists have many different ways of teaching and working. But where do these commitments overlap? What is "feminist pedagogy"?

I think that many of us have a crude stereotype in our minds that pops up when we imagine a "feminist professor." Not all feminist professors are women, nor are all women professors feminist. More importantly, not all professors who are feminists teach in a particularly feminist way.

Many self-declared feminists have been criticized justly for ignoring the perspectives of people of color and/or trans and nonbinary people, but the core principles of feminist pedagogy are radically inclusive and democratic. Based on my reading, here's how I would summarize those principles:

- An insistence that education be applicable to life outside the classroom, and particularly that it be a useful tool for understanding and undertaking real struggles to transform and liberate a society (and one's own mind) controlled by patriarchal norms;

- An effort to make classroom spaces more collaborative and egalitarian or democratic, in which the instructor does not dominate or control the learners and in which all participants contribute to a shared endeavor of discovery while entitled to their own distinct perspective;

- The validation of lived experience, including feelings and emotional responses, as a source of knowledge and as a useful lens for critical analysis, in addition to rational thought and logic.

You'll note that none of this is limited to women teaching, to teaching women, to teaching about women, or to the discipline of Women's Studies. Feminism is for everyone.

And many feminist pedagogical approaches are not unique to feminists: feminists did not invent discussion-based classes (they're arguably as old as Socrates, at least) or courses on revolutionary ideas of social change (also a favorite of Socrates, actually). It's these underlying principles that define feminist pedagogy – the "why" of certain teaching strategies.

Chronologically, the "second wave" feminist movement followed the "first wave," i.e. the campaign for women's suffrage culminating in the 19th amendment in 1921. In pop culture, it took early inspiration from works like Simone de Beauvoir's 1949 The Second Sex (published in English in 1953) and Betty Friedan's 1963 The Feminine Mystique. Within higher ed, the first women's studies departments were established in the 1970s. They drew in a heterogeneous mix of students including older women who had never gone to college, as well as students immersed in counterculture and social movements of all kinds, including the Civil Rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement.

Feminist pedagogy vs. critical pedagogy

Feminist pedagogy responds to and builds on critical pedagogy, particularly on Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed (first published in English in 1970). An extremely abbreviated summary: Freire criticized what he called the "banking" model of education, in which an instructor fills up the student, a passive empty vessel like a piggy bank, with knowledge, constituted as one single, fixed truth. Freire found this model of education dehumanizing and oppressive. In Freire's native country of Brazil, teachers were often white managerial class, and learners were often indigenous working class or poor. Freire envisioned – and actually created – an educational program where learners identified problems that were important to them in their daily lives, and instructors supported them in answering their questions about those problems, and then in connecting the answers to a deeper, critical analysis of systems and culture, a process called "conscientization." Elizabeth Kamarck Minnich writes that "The critical attitude leads us to seek the deepest level, the level of unquestioned assumption..., and then asks of the un-questionables what purpose they serve – and whose purposes they serve." Instructors learn as much as their "students" do through dialogue. (I wrote about the Highlander Center's similar pedagogical approach in my last post.)

Freire also called for revolutionary praxis, a continuous cycle of reflection and action to transform the world into a more just place. Theory and dialogue and critical consciousness were not abstract intellectual or academic endeavors, but the necessary precursors to action, and a necessary step in reflecting on and learning from action afterwards. Critical pedagogy prepares people to participate in counter-hegemonic or radical social movements, grounded in a higher-level understanding of what they are doing and what they are seeking to change. Feminist pedagogy adopts the same mission. Students learn about patriarchy in order to challenge and change it. The classroom is always connected to the world outside it.

At no point, however, does Freire discuss how gender or patriarchy (or machismo, misogyny, homophobia, heteronormativity, etc.) fit into his analysis, a blind spot he did begin to correct in later works.

In 1989, Elizabeth Ellsworth published an essay, “Why Doesn’t This Feel Empowering? Working Through the Repressive Myths of Critical Pedagogy.” In the wake of a racist incident on campus (a frat party with a racist theme), Ellsworth offered a senior seminar in anti-racist pedagogy at the University of Wisconsin, in which she attempted to put Freirean critical pedagogy into practice. She co-designed the syllabus with students, facilitated dialogue, empowered student voices, and presented herself as a fellow learner rather than an instructor.

However, she found that the result was not the egalitarian utopia she'd envisioned. She still had authority tied to her role as a professor, and students were skittish in challenging her misconceptions and blind spots. (Susan Stanford Friedman, in her chapter "Authority in the feminist classroom: a contradiction in terms?," explores the same problem, and wonders if it's also anti-feminist to renounce the authority that women are so often denied in the first place.) In Ellsworth's class, women and other marginalized students also still felt excluded from the dialogue, especially when they felt that their experiences were not regarded as valid by their classmates unless framed in academic discourses of rationality and logic – as if the burden of proof fell on them to debate their own right to speak or feel or perceive reality, and if they lost the argument, they'd be obliged to abandon their knowledge of the truth.

To her credit, Ellsworth realized that there was a problem, and engaged in ongoing dialogue with students about how to address it. "We began to see our task not as one of building democratic dialogue between free and equal individuals, but of building a coalition among the multiple, shifting, intersecting, and sometimes contradictory groups carrying unequal weights of legitimacy within the culture and the classroom." Sometimes, inviting everyone to participate in dialogue wasn't actually more fair; sometimes it was more fair to give the floor to one group of students at a time to offer their perspective or "partial narrative," and for others to listen quietly and reflect on their own, different, partial narrative. These differences were not always reconciled to form consensus, but solidarity could still be built across them. Solidarity is an important goal of feminist pedagogy, as articulated in “‘Under Western Eyes’ Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles,” by Chandra Mohanty. Mohanty makes a distinction between women's studies syllabi that treat women in the Third World (or "the Two Thirds World," her preferred term) as objects of tourism or voyeuristic exploration, rather than viewing them in a spirit of solidarity across borders and time, with shared experiences of domination as well as resistance.

Feminist pedagogy's response to critical pedagogy is not just a question of adding discussion of gender and patriarchy to the conversation. It's also about acknowledging and managing unequal power dynamics among learners more broadly. This power imbalance produces tension and sometimes conflict, and so feminist pedagogy is actually less concerned with creating a "safe space" (or, as this term is often understood, a space that always feels comfortable and affirming) than with building a community for sharing knowledge from different perspectives, and criticizing misconceptions. bell hooks, once Chandra Mohanty's colleague at Oberlin, writes:

The presence of tension—and at times even conflict—often meant that students did not enjoy my classes or love me, their professor, as I secretly wanted them to do. ...Moving away from the need for immediate affirmation was crucial to my growth as a teacher. I learned to respect that shifting paradigms or sharing knowledge in new ways challenges; it takes time for students to experience that challenge as positive. (Teaching to Transgress)

Ways of Knowing

"I think, therefore I am." The "Cartesian" way of creating knowledge is through "pure reason" and logic, an attempt at objectivity and universal truths. But we all know a lot of things that we didn't learn by sitting in a room by ourselves and thinking about it. Our experiences, our senses and our feelings about what we sense, also shape what we know and what we believe. Most of us learned about pedagogy through experience and feeling rather than logic or data, come to think of it. And because we each experience and notice different things from the vantage of our own standpoint, our knowledge and beliefs are different.

Feminist theory and the feminist movement embrace the value of multiple ways of knowing, and the coexistence of endlessly different standpoints and perspectives. As Berenice Fisher points out, "Being a woman in a patriarchal society means being someone whose experiences of the world are systematically discounted as trivial or irrelevant, unless they relate to specifically feminine concerns, or unless they are the experiences of 'exceptional' women." Susan Stanford Friedman calls this the "patriarchal denial of mind to women." I would add that the experiences of people of color, queer or trans people, working class and poor people, and other marginalized people are similarly systematically discounted. Feminist pedagogy calls for empowering people to find their voice and to narrate their experience as a valuable source of knowledge, even or especially when they've been socialized not to (or silenced in other classes or spaces at your own institution), and even or especially when their experience contradicts how someone else sees the world.

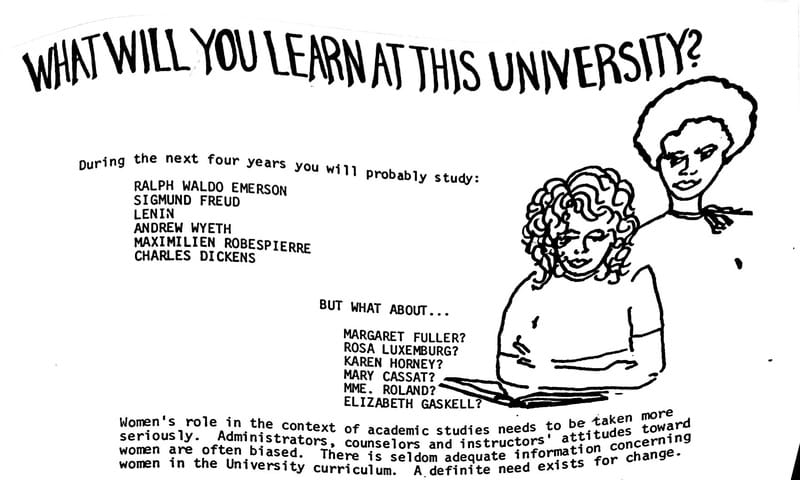

In terms of pedagogy, this means that course content and curricula change, because other people's experiences become useful texts from which to learn. Oral histories and storytelling, interviews with practitioners or community members, and works by non-academics gain value, because they offer a broader spectrum of perspectives and experiences. Students don't just learn about non-canonical artists and authors and history; they also reflect on why such artists and authors and history are "non-canonical" in a patriarchal curriculum. The result is a more egalitarian curriculum, and opportunities (as well as a responsibility) to discuss why traditional curricula are not egalitarian.

Discussions also take on quite a different nature, and the rules of engagement are different. Instead of being forbidden to say "I think" or "I feel," learners are positively encouraged to share opinions, stories, and personal interpretations. Journaling, reflecting, and group work become more valued uses of time. But if learners are going to share stories, they need to have some level of trust in the other people in the room that they will be believed and not gaslit, abused, or retaliated against. Building community becomes a precondition for an effective class in which all participants contribute to creating knowledge. Adrienne Maree Brown calls this "building a container."

bell hooks and other feminists challenge professors to show up as their whole selves in the classroom, multidimensional and embodied humans, as opposed to professionalized talking heads. In Learning Our Way, Evelyn Torton Beck writes about the feminist professor's choice to disclose information about herself in the classroom, to name her own standpoint and experience. Self-disclosure dismantles the pretense of objectivity and makes the professor vulnerable, opening a door to kinds of interactions with students that you may not want, but most (not all) students also see it as humanizing. Beck writes that "Surprisingly, I have decided that what is most important is not necessarily the act of disclosing, but the state of being ready to self-disclose," because it shows "internal integration" and consistency between feminist theory and the act of teaching. If experience and standpoint are important, sometimes it is organically relevant and impactful to self-disclose how you know what you know.

Incompatible with Academia?

My reading on this topic included a volume from 1983 called Learning Our Way: Essays in Feminist Education. I thought I'd skim the introduction, and then ended up reading half the book. In 1975, 200 feminists from across the U.S., many of them academics, had gathered in Vermont at an institute called Sagaris to try to hash out what "radical feminism" really was. Many of the participants contributed to Learning Our Way. By the 1980s, it seems to me like they'd formed some points of consensus about what a feminist curriculum was and how feminists ought to act within higher ed.

They'd also started to articulate irreconciliable lines of difference among distinct groups or sects (or pedagogies) within the movement – particularly between "liberal" and "radical" feminists. In her essay "If the Mortarboard Fits," Sally Miller Gearhart explained that liberal feminists seemed to want equal representation and authority for women professors in higher ed, and equal access to higher education for women students. Radical feminists, by contrast, felt called to change higher education in more profound ways, because radical feminism is, in Gearhart's estimation, "incompatible with academia." The academy is a product of a white supremacist patriarchal capitalist society, which is reflected in the various hierarchies and power dynamics within academia, as well as being reflected in its exclusion of many people who are kept outside it.

Academia brooks only token deviance from its norms, just enough to demonstrate its democratic principles or its "innovative" atmosphere. It offers survival and acceptance (graduation, a job, prestige) to those who will quietly take their place on the assembly line or who are themselves willing to be mutilated into professionals. Feminism, on the other hand, claims wholeness to be possible and desirable. Early on, the women's movement challenged the "myth of the half-person," i.e. the existence of something called "femininity" and something else called "masculinity" in human beings, and it deplored society's overvaluing of rational ("masculine") functions (objectivity, logic, analysis, linearity) to the near exclusion of nonrational ("feminine") functions (subjectivity, emotionality, intuition, synchronicity). Academia – even the woman's college – is based on the myth of the half-person and stubbornly continues to lay out its fragmented disciplines in patterns that perpetuate stereotypes of “men’s work” and “women’s work” (science-math-we-know-the-list versus nursing-teaching-and-we-know-that-list-too). Academia fears the unpredictability (read “uncontrollability”) of nonrational functions. (Sally Miller Gearhart, “If the Mortarboard Fits”)

Academic disciplines, institutions, departments, and programs are institutions that demand to be maintained and perpetuated, and that resist change. The longer a radical feminist spends in academia, Gearhart warns, and the more they build there, the more committed they will become to upholding the institution's interests instead of transforming the institution. A radical feminist had to be able to leave the institution at any time, and to "watchdog the compromises" made by others in the institution – and those they make themselves. They had to continually remind themselves to connect with others in solidarity, rather than succumbing to the temptation either to compete against colleagues or to retreat from society into an ivory tower. bell hooks criticizes the "the segregation and institutionalization of the feminist theorizing process in the academy, with the privileging of written feminist thought/ theory over oral narratives." Feminist theory, she writes, defeats its own purpose when it is incomprehensible to non-specialists, even though (or because) incomprehensible theory is valued more highly in the world of academic scholarship.

In her 1981 essay "What is Feminist Pedagogy?" Berenice Fisher points out that women's studies was already consolidating and sedimenting into a fixed discipline with a fixed body of knowledge. You could be an expert in feminism, even a better expert than others. Already, there was a risk of representing any one feminist perspective or any one theoretical approach as the right way to do feminism – but claiming one correct truth was fundamentally anti-feminist. The discipline's own process of being institutionalized posed a threat to its integrity, even when it was less than a decade old. No one wants to burn down the house they live in.

Takeaways

I found my reading about feminist pedagogy (which has barely skimmed the surface, frankly) to be really exciting and affirming. The insights I found are still radical (mostly, with some big blind spots) 40 or 50 years later, and they still offer a powerful alternative vision of a professor's role. We don't have to control our students, dumping as much of our knowledge into them as we can, replicating the body of knowledge that was once transferred to us. In fact, we shouldn't. We do not have to accept the traditional academic maxim that "relevance" to real life is an enemy of intellectual rigor, cheapening the purity of logic and pandering to pop-culture obsessed students. We also don't have to separate our real selves, who need fair labor conditions and physical and emotional wellbeing, from our academic selves. We don't have to pretend to be neutral (which reinforces the status quo) or objective (which is impossible), or make challenging ideas palatable (unless our jobs depend on teaching evaluations, which they often do, but maybe even then). We also don't have to hide our own expertise or avoid providing any structure, as Freire might advise, or deny that our own standpoint is only one of many.

We do, however, have to take our students' viewpoints and experience seriously, and support them in interrogating – for themselves – patriarchal systems at work around and inside them, including in higher ed. And we do have to help students relate to us and to each other in such a way that they can all volunteer personal reflections and critiques of one another without screaming. Caroline Shrewsbury writes that "The feminist teacher is above all a role model of a leader. S/he has helped members of the class develop a community, a sense of shared purpose, a set of skills for accomplishing that purpose, and the leadership skills so that teacher and students may jointly proceed on those tasks."

Reading I Recommend

Bunch, Charlotte, and Sandra Pollack. 1983. Learning Our Way : Essays in Feminist Education. Trumansburg, N.Y: Crossing Press. - especially Sally Miller Gearhart, “If the Mortarboard Fits,” and Elizabeth Kamarck Minnich, “Friends and Critics: the Feminist Academy”

Culley, Margo, and Catherine Portuges, eds. 2013. Gendered Subjects : The Dynamics of Feminist Teaching. London: Routledge. - especially "Taking women students seriously" by Adrienne Rich and "Authority in the feminist classroom: a contradiction in terms?" by Susan Stanford Friedman