Educating for Power: pedagogy at Highlander Folk School

Highlander was all about empowering marginalized, oppressed people to realize how much they actually already knew, to find solidarity with others around them, and to use their knowledge to bring about social change together.

In October of 2020, I attended a webinar that absolutely blew my mind. I don't think I've ever opened so many tabs to read later in the space of an hour. The Zinn Education Project hosted the webinar, part of its "Teaching the Black Freedom Struggle" series (still going!). Professor Charles Payne of Rutgers University-Newark was talking about his new book about the civil rights movement and the topic of "Organizing for Voting Rights: Lessons from SNCC."

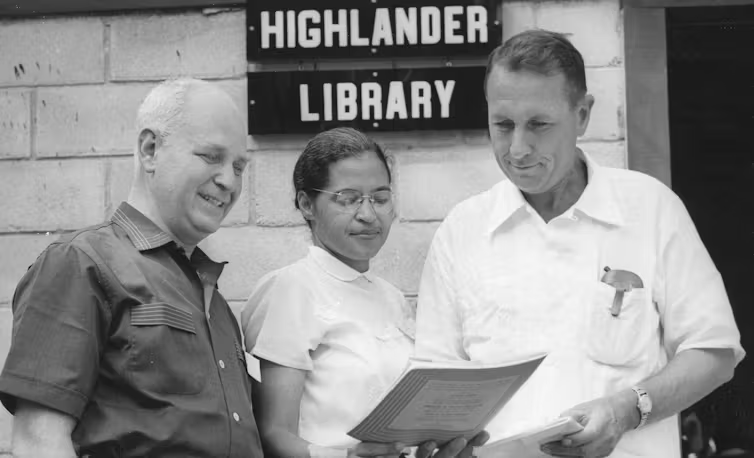

As I later fell gleefully down a rabbit-hole reading about founding figures of the civil rights movement like Septima Clark and Ella Baker, I eventually landed on Myles Horton and the Highlander School, an institution in Tennessee where Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, and many other luminaries of the civil rights movement had studied and trained as movement leaders.

I'd never heard of Highlander before, although they're still doing important work today – at a new site, since the old one, donated to them by a wealthy patron, was raided by the FBI and shut down in 1961 because they defied Tennessee's segregation laws by training racially integrated groups of activists. In fact, Horton often hosted trainings for the CIO, the UAW, the UFW, and other union groups but refused to let them go on unless and until they brought Black workers and women into the groups. Highlander, Rosa Parks said, was the first place where she met white people she felt she could trust, and it was the first place where John Lewis said he'd ever sat down to eat with white people.

To be clear, Horton didn't teach these leaders how to organize, nor did he turn them into leaders. What he did was create a space where they could gather safely to think critically about shared problems, deliberate on strategy, reflect on principles, and imagine a better world, as well as bonding over shared meals and songs. Occasionally he'd tell a story about something he'd experienced or read.

Myles Horton founded Highlander as a place where adults could come to learn from one another. Horton's pedagogy (or "andragogy," education for adults (andra-) rather than children (peda-)) was all about empowering marginalized, oppressed people to realize how much they actually already knew, to find solidarity with others around them, and to use their knowledge to bring about social change together. (He was not a Communist, and in fact says that he was told he could not join the Communist Party because he wouldn't toe their party line.) The results were transformative, both for the learners and for the United States.

Poor people have been encouraged to find beauty and pride in their own ways, to speak their own language without humiliation, and to recognize their own power to accomplish self-defined goals through social movements built from their own kind and kin. ...People learn about unity by acting in unison. They learn about democracy by acting democratically. Each time they act in democratic unity, as a result of Highlander experiences, they both strengthen their capacity for such action and demonstrate the process of education. (Unearthing Seeds of Fire: the Idea of Highlander)

Highlander's origin story

In 1987, near the end of his life, Myles Horton sat down with Paulo Freire, author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, for a conversation at Highlander. The two had served on panels and met before at conferences on adult education and critical pedagogy, but had never had a real conversation before. They had decided to "speak a book," or have a conversation that would be recorded and edited into a book: We Make the Road by Walking. They discovered important commonalities, although Freire grew up in an industrial city in Brazil and Horton in rural Appalachia. Both grew up poor, but more importantly, surrounded by inequality: some of their peers had food and books and parents with steady jobs, and many did not. Both wondered why. Neither one was particularly stellar in school (and neither had access to a local public high school): Horton was always reading things that weren't assigned and talking back to teachers, and Freire says he often felt stupid in school because he didn't understand bureaucracy or fall in with the discipline of rote learning. But perhaps because they both reacted so strongly against authoritarian teaching, both fell in love with autodidactic reading and, eventually, teaching. For both men, teaching and learning were liberatory acts, full of joy and excitement.

Horton went to the University of Chicago (where he hung out with Jane Addams at Settlement House) and then east to Union Theological Seminary in New York City, where he studied under (and befriended) radical social philosopher Reinhold Niebuhr. He then returned home to rural Tennessee, to teach Bible study for children. What he really wanted to do was teach adults, so he invited his students' parents to night classes. None had cars, so they walked. He talked about the Bible a little, then asked them to talk about the problems they were facing with working conditions and their health.

I knew more than they did about a lot of these things, because they might know about the specific situation but they didn't link it up with other situations, with general situations. So I was able to help them a little bit, putting it in some kind of perspective. But that soon ran out; that soon was exhausted in terms of dealing with their problems, and I had to tell them that I didn't know these answers. ... So I said: "Well let's talk about what you've done, maybe what you know will help somebody else and what they've done to help you. Let's talk about what you know. You know this better than anybody else. You don't have any answers, but you know the problems." That was the beginning of this understanding that there's knowledge there that they didn't recognize. I didn't have any terminology for this or any concepts for this but that's what it was, you see. And to my surprise and to their surprise--we were all equally surprised because we were all equally naive about this--before the evening was over people began to feel that from their peers they were beginning to get a lot of answers. (We Make the Road by Walking)

This was the seed that grew into the Highlander Center (founded in 1932), a place where local Appalachian people could come to reflect on and critically analyze their experiences, and share knowledge with each other.

Early on, Myles Horton went out to connect with unions in the surrounding mining towns and offered to support their efforts to organize. Strikes were illegal, and many Tennessee unions were resisting the oppressive conditions of company towns, where workers' only option to buy food and supplies was the company store, with prices jacked up so high that their wages all went right back into the company's pockets. This was still the era of the Great Depression, leading into the New Deal. Horton was beaten up, shot at, and jailed multiple times along with other organizers, but developed a reputation for helping unions to win better contracts and working conditions, even across race lines:

After signing up a majority of the white workers, Horton sought out leaders in the black shops. The black workers were suspicious of him, but, finally, he was taken to a man who was never introduced by name and who said not a word during their brief meeting. Horton said what he had to say: the union was for everyone; every black worker could join, and join the fight for a twelve-dollar minimum for forty hours; this would cut blacks' working hours from sixty to forty each week, and double their pay–if the union won. ... During the final bargaining session, the company president told them, "These colored people work on my plantation and they work in my mill. They are good boys and I think we ought to do something for them. I understand how you Southerners feel about it, but I'm a Republican from Pennsylvania." "No," Horton replied. "Don't do anything special for them. They'll be satisfied with what the rest get.” "You mean they are covered in the contract?" the president shouted, his face paling. "The minimum will double their wages and cut their hours. You don't mean to say you expect me to pay them twelve dollars?" "See the contract," Christopher said. "That's what it says. You signed it." The president blew up, swearing that he would fire the blacks before he would pay. To pay blacks that much was unreasonable and unheard of, he claimed. What seemed to bother him most, according to Horton, was the possibility that the contract would draw the scorn of fellow industrialists, and be a model for other locals. Evidently, however, the desire to keep his mill running triumphed over the desire to save face. The next payday, every worker received the twelve-dollar minimum. (Unearthing Seeds of Fire: the Idea of Highlander)

A minister in Chicago invited Myles Horton to go to Denmark to learn about the tradition of folk schools there, as a possible model for Highlander. In the late 19th century, Denmark had been suffering the after-effects of losing two wars with Prussia, and a bishop decided that the solution to restoring national pride was to develop a non-traditional school program for "fostering the integrity and natural intelligence of village and farm people" over the age of 18. Some schools eschewed books entirely, favoring oral history and traditional songs. Horton found school communities having lively discussions about social problems, large and small, led by idealistic teachers "on fire to correct injustice, to awaken the peasants to the misery restricting their lives" who supported people in developing "'a picture of reality not as we have met it in our surroundings, but as we ourselves would have formed it if we could—a picture of reality as it ought to be'" (Unearthing Seeds of Fire).

In 1981, Bill Moyers interviewed Myles Horton, labeled "the Radical Hillbilly." The whole interview is delightful, but in this clip, Horton describes his teaching philosophy born from his work with unions and his study of the folk schools:

Horton's pedagogy - until about minute 12

By Horton's own description, this pedagogy was learned through trial and error – by "falling flat on our face." He and the other teachers brought professional techniques and their world travels and theoretical readings to workshops, and met a brick wall. They realized that:

the solutions we have are for problems that people don’t have, and we’re trying to solve their problems by saying that they have the problems we have the solutions for. That’s academia. So what we’ve got to do is to unlearn much of what we’ve learned and then try to learn how to learn from the people. In other words, instead of learning from what we learned academically, we’ve got to learn how to relate to their experiences. ("Radical Hillbilly")

Like Paulo Freire in Brazil, Myles Horton and the Highlander team learned that they needed to get to know people and learn about them, learn about their problems – material and immediate as well as systemic – in order to facilitate learning effectively. They had to learn from their learners, and start from where they were. The result was a group of learners who came away from the experience knowing more, but who were also eager to keep learning and to teach others what they knew because it had direct relevance for their lives. They also had a new consciousness of their own knowledge and experience as a source of power, a valuable resource to share with others, and a driver of action. Today, we'd call Highlander's model a "train-the-trainers" approach. They never facilitated groups bigger than 30, to make sure that they were prioritizing deep learning in community.

Highlander and the Civil Rights movement

In some ways, the Civil Rights Movement was born in the labor movement: A. Philip Randolph and E.D. Nixon helped to organize the Pullman porters' union before becoming leaders in the NAACP and the Black voting rights movement. E.D. Nixon had worked with Myles Horton on labor organizing, and he sent Rosa Parks and other NAACP leaders to Highlander to discuss their problems and goals, and to study the philosophical foundations of nonviolence. Highlander was also the first gathering place for the college student leaders of the sit-in movement, where they first agreed to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Horton separated the students from the adults at Highlander, finding that "The students were glib, and their easy answers, while they impressed the parents, constrained the adults from reaching their own appropriate and practical solutions to their problems."

One of the first NAACP leaders to come to Highlander was Septima Clark, a Black schoolteacher in South Carolina. She eventually assumed leadership at Highlander as the director of education, working to organize and educate Black communities. At Highlander, she met Esau Jenkins (who ran a bus service for Black workers) and worked with him to set up Citizenship Schools in the Sea Islands of South Carolina, where adults could come to study for the literacy test they needed to pass in order to vote. At first, Jenkins had asked adults to come to the local elementary school to study alongside children, but he couldn't get them to stick with it. Highlander staff helped him to set up a new program just for adults, with adult-sized furniture, where they could learn to read by studying the South Carolina constitution (one component of the literacy test) and the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights instead of children's books, or learn to fill out money orders or whatever else they identified as useful.

Myles Horton kept himself in the background of these efforts. He spent a few months in the Sea Islands chatting with locals to learn about what kind of program people were asking for, but he insisted that the teachers and main organizers of the program needed to be members of the local community, preferably people who spoke Gullah, and not traditional teachers by training.

Mrs. Septima Poinsette Clark, later Highlander's director of education, has told in her book, Echo in My Soul, how one of her associates in the Charleston, South Carolina, black branch of the YWCA, Anna Kelly, felt after the workshop she attended: "She came home fairly bursting with enthusiasm . .. reported on the workshop .... and at once began planning ways of getting across to our people the subjects discussed there, particularly those relating to desegregation; she also called in representatives from various clubs and planned a series of radio broadcasts. But she was especially interested in recruiting Charlestonians to attend forthcoming Highlander workshops." What Anna Kelly did is what Highlander had hoped would be a result of the workshops and illustrates the school's philosophy: work through local people as they seek to improve their own communities; work with an immediate, specific problem, with the hope that, when people facing the same problem are brought together, a social movement will emerge. (Unearthing Seeds of Fire)

The Citizenship Schools spread, tripling the number of African American registered voters in the area. In 1961, the program had grown so big that Highlander suggested that Septima Clark bring it to a new home with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as its own entity, where Dorothy Cotton became its director. By 1970, they'd educated 100,000 African Americans across the South to pass literacy tests and register to vote.

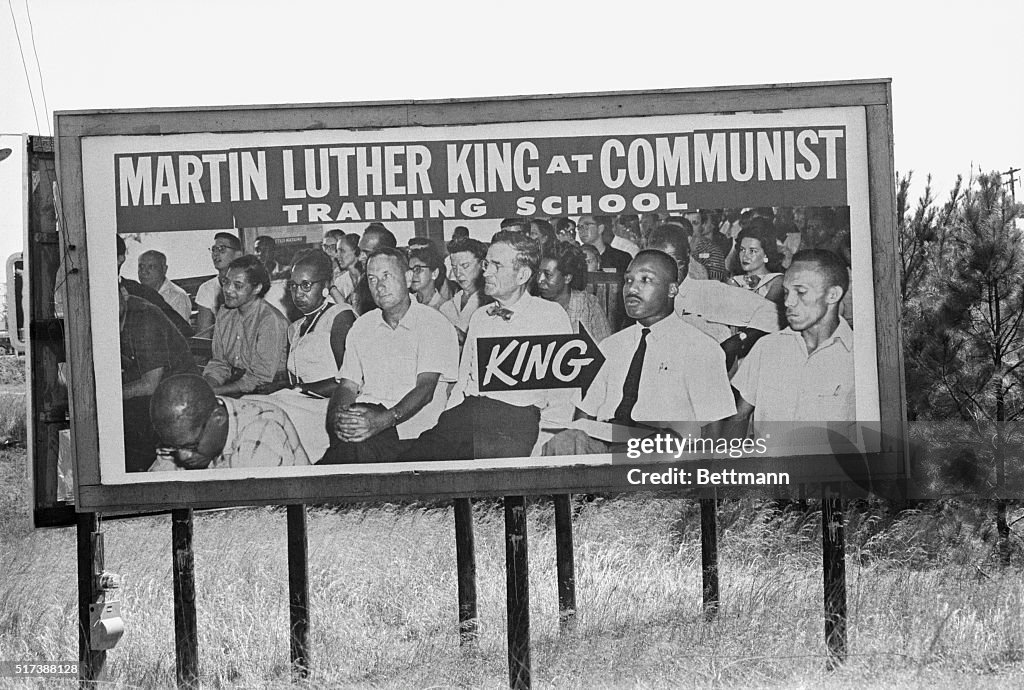

Lessons from Highlander

It had never occurred to me that the leaders of the Civil Rights movement had been trained to do what they did (and I certainly didn't learn that in school), but of course organizing and engaging in nonviolent direct actions didn't just pop into their heads one day. And it had never occurred to me that the Civil Rights movement and the labor movement had anything to do with each other, that mining unions and Rosa Parks shared a common methodology and social outlook to some extent. But of course it makes sense that these leaders had to think deeply and learn about the philosophy of nonviolence in order to have the spiritual strength, vision, and strategic insight to do what they did. It's also not an accident that both movements were subject to fear-mongering and propaganda falsely smearing them as Communists, since they were empowering people to identify, critique, and work to dismantle systems of oppression.

There can be no such thing as neutrality. It's a code word for the existing system. It has nothing to do with anything but agreeing to what is and will always be—that's what neutrality is. Neutrality is just following the crowd. Neutrality is just being what the system asks us to be. ...Now as a matter of strategy, I very seldom tell people what my position is on things when we're having discussions, because I don't think it's worth wasting the breath until they ask a question about it. When they ask about it, I'm delighted to tell them. Until they pose the question that has some relevance to them, they're not going to pay any attention to it. (Myles Horton, We Make the Road By Walking: Conversations on Education and Social Change)

The incredible impact of Highlander is a testament to the power of education that treats learners with respect and dignity, and meets them where they are, letting them lead the way. People (especially adults) are curious and eager to learn about ideas and skills that can help them address their real, everyday problems. Freire's emphasis on "problem-based education" and the Danish folk schools' interest in people's reality get at this same basic principle. Highlander also set out to be a place not where people could learn from experts, but where people could learn from their neighbors and peers – they already had valuable knowledge to share. This teaching philosophy required a very un-traditional and humble stance for the instructor or educator, but led to more profound learning.

In formal classrooms, we aren't allotted much time and latitude to let our students determine our curriculum, or much control over class size. Our students haven't invested their time and energy into traveling to rural Tennessee to seek out liberatory education, so we might have to go further to meet them where they are. But I think it's worth contemplating how we can create space for students to discover, investigate, and reflect on social problems together, rather than telling them how to understand the world.

The other lesson I take from reading about Highlander is that developing a new, people-centered pedagogy can take a long time, and it might not work very well the first few times around. An iterative process of trial and error is still worthwhile, though, in pursuit of that a-ha moment when you finally see the kind of learning you want. Highlander staff kept changing their methods until they saw their goals realized: creating the conditions for participants to want to discover ideas for themselves, and empowering very different people to work through shared problems.

One last note: Horton discovered early on that it was hard to get adults talking in his classes. His first wife, Zilphia, was a trained musician and began to start each session with communal singing, which had a magical effect of opening people up and bonding them together. Highlander is where many civil rights leaders first learned "We Shall Overcome," a movement song first sung by striking tobacco workers in Charleston in 1946. Pete Seeger's album of union songs includes another, "Bourgeois Blues," that Zilphia sang with Leadbelly, but this one is my favorite from the album:

My favorite song from Pete Seeger's album of union & movement songs

Reading & watching

"Highlander." TN History For Kids.

Documentary clips from "You Got to Move: Stories of Change in the South." - check out "They Say I'm Your Teacher" about Septima Clarke.