Making feedback worth your while

To be helpful, feedback should focus on helping students to improve their work, not on evaluating them. And it should connect back to expectations that were clear from the start.

The thing I miss least about my life as an academic is formatting bibliographies. But a close second is grading. It was repetitive and tedious, it was time-consuming, it felt punitive, and sometimes it led to arguments with students. And as I wrote comments to justify the marks I gave, I wondered: is anyone even reading this?

I was curious to find out what the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning has to say about best practices for providing feedback to students. Of course, I found that it's complicated: the effectiveness of feedback (i.e. how much the feedback helps you do a task better next time) depends on the type of task, the learner's proficiency going in, the learner's age and culture and personality, their relationship to their instructor, the timing of the feedback relative to the task, and other factors. But I did find some articles that addressed the problem of how to get students to engage with feedback. After all, it's only feedback if you use it.

Grades are themselves a form of feedback, but not a very good one: they're an extrinsic system of rewards and punishments that often seem arbitrary, which can reduce students' intrinsic motivation to learn. Grading on a curve is particularly demotivating – comparing students to each other just makes learning into a zero-sum game, and tells students little to nothing about how they might improve. We might hope that lower grades will motivate students to try harder and do better next time, but research shows that they often have the opposite effect: they demotivate students who were already struggling. Assigning a numerical value to an essay is to some extent, as David Clark writes in the blog Grading for Growth, "objectivity theater:" numerical grades mask subjective criteria and instructors' individual tastes or preferences, dressing them up in numbers that look objective.

These limitations of grading have led to various sects in academia abandoning traditional grades in favor of "specifications grading," "mastery-based assessment," "ungrading," and other variations. Advocates of alternative grading systems are quick to point out that grades have only been a feature of higher education for a few hundred years (which is not very long, when you think about how old the universities in Oxford and Bologna are!). They were introduced at Yale because oral exams were thought to be too subjective and covered too little ground. For decades, institutions like Brown and Hampshire College have given students the option of completing coursework without letter grades. In the book that came out of the blog Grading for Growth, Talbert and Clark note that students during the Vietnam War could get deferments based on high grades, which led several more colleges to stop giving grades altogether. The COVID19 pandemic sparked another era of institution-wide experimentation with "ungrading."

At Wesleyan, where I went as an undergrad, students in the College of Letters (a humanities program) received written feedback instead of grades on their work, and everyone I knew in the program said that the written feedback hit them much harder than a grade would have. They were excellent students to begin with, and they were used to feeling pleased by their grades; in fact, like many students receiving high grades, they might not have bothered reading feedback after seeing an A. Getting a whole report on their strengths and weaknesses was much harder to take, especially without the positive reinforcement of a high grade. Research shows that feedback like this, unaccompanied by grades, is most helpful in supporting students' improvement and progress.

Still, it's a huge undertaking to replace your entire grading system in a course, and not every institution is willing to forgo grades. If we do have to put numbers or letters on students' work, what kind of feedback can we give that will actually be useful?

1) Provide opportunities to put feedback into practice

The first thing we can do, perhaps the most important, has nothing to do with the form of the feedback itself. Feedback is only useful if the learner has an opportunity to put it into practice, and to try the same task – or a very similar one – again after receiving it. Otherwise there's no "loop" in the "feedback loop," and no opportunity to demonstrate growth. Students should have the option of resubmitting an assignment after receiving and incorporating feedback. This is one of the features that makes an assessment "formative," or supportive of further learning, rather than "summative," meant only to evaluate the learner at a particular point in time. Peer workshops on assignments before the final due date are one way to get feedback to students at a time when they can actually use it (and students may actually learn more from giving feedback than from getting it). Panadero and Lipnevich discuss ways of facilitating "agentic" use of feedback, by students who feel a sense of purpose and agency in reading and attempting to implement feedback from their instructors.

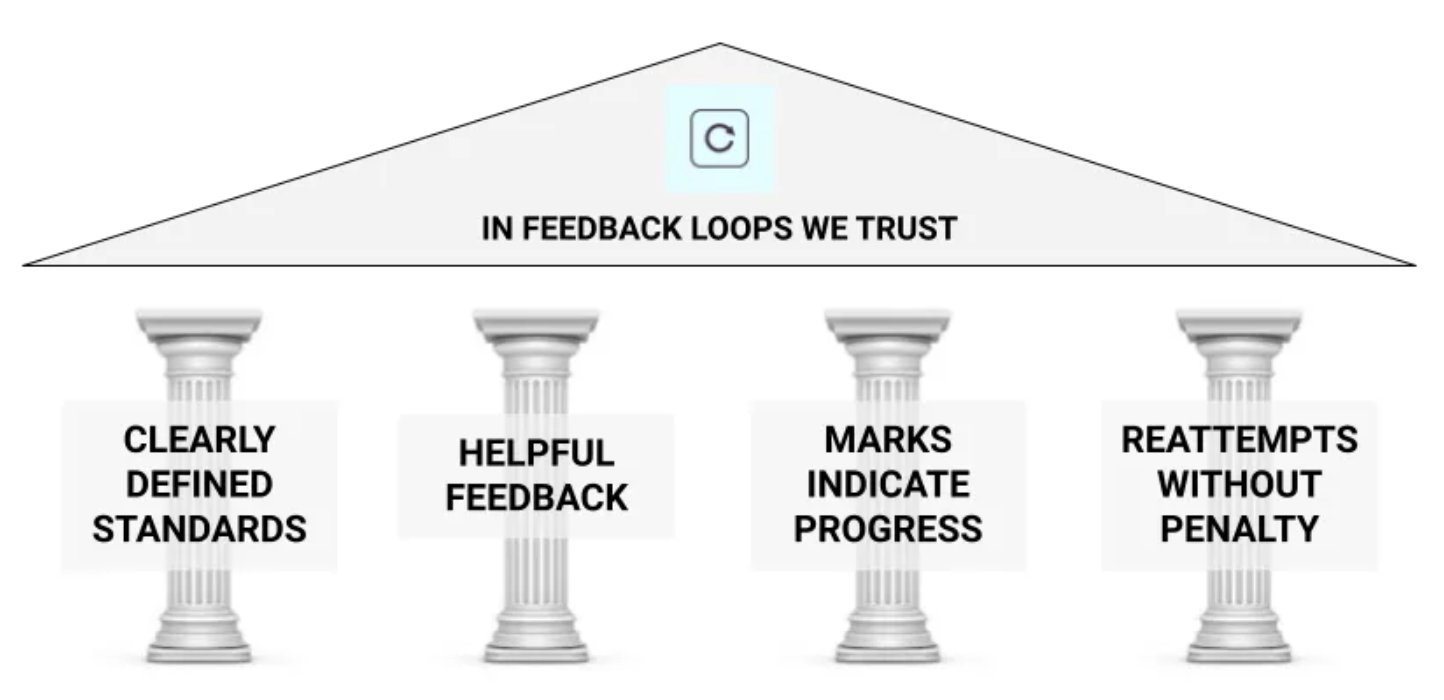

Robert Clark's infographic on Grading for Growth captures this principle in his fourth pillar of effective feedback loops (I'll come back to the others):

2) Feedback shouldn't come as a total surprise

Clark's first pillar, "Clearly Defined Standards," is crucial as well. Feedback is most powerful when it tells the learner how close they got to a certain standard that they're already familiar with, and also how they might get closer to that standard on their next attempt. In the The Cambridge Handbook of Instructional Feedback, I found a pithy, powerful observation from Jacques van der Meer and Philip Dawson: "Feedback too often functions as retrospective clarification of expectations."

When I was a student, some of my final papers just seemed to miss the mark in terms of the topic or argument I had made (a topic I've written about before). It was incredibly frustrating to be penalized for something I didn't know was wrong. Was I supposed to read my professor's mind? Did everyone else know something I didn't? It's particularly common for first-year students, neurodivergent students, and first-generation low-income college students to experience this kind of confusion, and particularly on writing assignments.

Sarah Silverman, an education scholar at the University of Michigan, wrote a Substack post recently about the perpetual struggle of "making expectations explicit." It's a very difficult thing to do. You never quite know if students will find your instructions transparent, even when you've made every effort to be clear and precise, so it's often an iterative process. She talks about her "Amelia Bedelia" moments, when, like the fictional character, she had interpreted directions too literally or otherwise missed the mark.

There are two basic ways to make grading criteria explicit up front. The first is providing a rubric ahead of time that defines what a successful, adequate, or unsuccessful assignment will look like, with as much precision as you can. The second is providing exemplars of work at each level. These two methods aren't mutually exclusive.

But van der Meer and Dawson have also gone a step further, and introduced assessment requirements as a topic of discussion in the classroom itself. They do a think-pair-share activity where students reflect on what they think a successful assignment will look like, then compare notes with a pair or group, and finally share their understanding with the class, and the professor can correct or add details as needed. They note that even when students disagree, it can lead to productive conversations about different conventions among academic disciplines. Students could also reflect on their own learning goals as a part of this conversation, identifying skills they'd like to work on. This conversation will make students more likely to be able to understand the feedback they receive, which they often find cryptic.

3) Feedback should be task-specific

I'm coming back now to Robert Clark's "Helpful Feedback" pillar – what does "helpful" really mean? Here, the research shows some surprising results.

In 1996, Avraham Kluger and Angelo DeNisi tried to address a problem in the literature: some studies had shown that feedback, especially without numerical or letter grades, had a powerful positive effect on student performance, while other studies found that it barely moved the needle at all. They broke feedback down into three categories:

- meta-task feedback on the learner themselves;

- task-motivation feedback on how the learner went about the task, how much and what kind of effort they put in; and

- task-learning feedback on whether they'd done the task correctly.

They found that meta-task feedback – even praise like "you're awesome!" – actually made people perform worse. (It is still important to remain positive and convey confidence in the student's ability to improve – posing feedback in the form of questions can help instructors to seem less authoritarian and punitive.)

In Kluger and DeNisi's study (and others), feedback was helpful when it helped learners to find a better strategy or approach, and focused on the task itself, not the learner. Instead of writing “great!” or “yes!”, it's better to write something like “well argued,” “I hadn’t thought of it that way before,” “elegantly expressed,” or “shows great understanding of the text."

Two New Zealand scholars, John Hattie and Helen Timperley, advise that effective feedback should answer three questions: Where am I going? How am I going? Where to next? In other words, feedback should tell the learner if they're making progress toward a given learning goal, and what they can do to get closer to that goal in the future.

Thomas Guskey writes: "We must ensure that students and their families understand that grades do not reflect who you are as a learner, but where you are in your learning journey — and where is always temporary. Knowing where you are is essential to understanding where you need to go in order to improve."

4) Feedback doesn't have to be very long or elaborate

Anders Jonsson's 2013 literature review addressed one of my original research questions on feedback: what can make a difference in whether students actually use it? He introduces research that shows that students usually won't bother to read feedback if they can't use it to redo their assignments or improve their work immediately in re-attempts or similar tasks.

As long as students get some guidance about how to do the assignment better or where they went wrong, even from copy-pasted boilerplate, extensive comments aren't necessary. It is just as helpful to provide feedback by circling descriptors on a rubric, providing exemplars, or asking guiding questions. In fact, Jonsson found that it's better not to give students a list of specific problems to fix, so that they have to think a little harder about how to implement feedback – and so that the feedback will be applicable not only to this assignment, but to future ones. It's better to describe strengths and weaknesses of an assignment or to ask questions to prompt improvements, rather than evaluating how good the assignment is or how good the student is. That said, it's important to identify specific areas for revision and improvement, because it's frustrating to receive criticism without knowing how to apply it.

Jonsson also refers to an interesting finding that audio feedback in the form of voicenotes seemed to be "read" and used by more students than written comments.

From theory to practice: short essay answers on exams

As I read about this topic, I thought about the exam questions I used to write. Often, in exams for my Roman Civ course, I provided interesting or important passages from our primary source course readings, and asked students to comment on them in a short essay. Why did I do that? (Beyond "it's what my professors did.") What did I expect? I wanted to:

- create an incentive to do the reading,

but I also wanted to prompt students:

- to describe what was in the passage, to show comprehension,

- to contextualize each passage in historical events, to show that they'd learned facts and chronology,

- to comment briefly on or even critique the author's perspective (were they talking about contemporary events as an eyewitness, or about events in the distant or even mythological past? Is the author Roman or Greek?), to show their mastery of that kind of information and their awareness that an author's perspective shapes their writing,

and/or

- to connect that passage to other parts of the source text, or to other readings, to show their knowledge as well as their ability to synthesize or make connections on a higher level.

To make sure that students understood these expectations, I could ask them in a class before the exam to reflect in a minute essay: what should a short essay response include to get full marks? I could give the class three sample answers and ask them to grade each one, and if they came up with a different grade than I did, we could talk it through.

For a rubric, I could write out descriptions of each score (being sure to use task-focused language) – this might be something I would do collaboratively with colleagues in a department meeting, perhaps with support from my campus Center for Teaching and Learning. (This AP rubric or these rubrics from University of Buffalo wouldn't be a bad starting point.) I could not only use that rubric to grade answers and provide feedback quickly, but staple the rubric to the exam going in, so that students would be able to consult it to regulate their own work on the spot during the task. And I might suggest that students re-read the exam and my feedback on the rubric before the next exam, to help them improve.

It might also be helpful to offer students an anonymous discussion board where they could ask for clarification about feedback, to encourage them to seek out feedback actively. Feedback won't do them any good if they don't understand it, but they might not want to sit down with me one-on-one in office hours to rehash criticisms of their work.

This doesn't guarantee that students will read or make use of feedback, of course. But for the ones that do, using task-focused language can make a difference. And being very clear about expectations and grading criteria up front can empower more students and give them a sense that they know what they need to do – which will make them more likely to read feedback in order to get there.

Further reading

Adding comments/feedback to assignments in Canvas: https://www.kent.edu/regional-campuses/quick-tip-provide-feedback-students-work-canvas

How students see comments in Canvas: https://community.canvaslms.com/t5/Student-Guide/How-do-I-view-annotation-feedback-comments-from-my-instructor/ta-p/523