Metamorphoses 11: Shape-shifters

I guess I wasn’t at my sharpest this week — blame it on the pandemic — because I didn’t really think about the importance of the presence…

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

I guess I wasn’t at my sharpest this week — blame it on the pandemic — because I didn’t really think about the importance of the presence of Morpheus, a god of dreams, in Book 11 of the MetaMORPHoses until I read Jay Reed’s note:

Morpheus’ name is conspicuously based on the central element (‘shape, form’) of the title of the Metamorphoses; the thematic nexus of dreams, ghosts, imitation, and shape-changing in his performance unites several of the whole poem’s concerns. His own shape is indeterminate; almost a pure metaphor for metamorphosis, he is given no identity beyond impersonations. (p. 476)

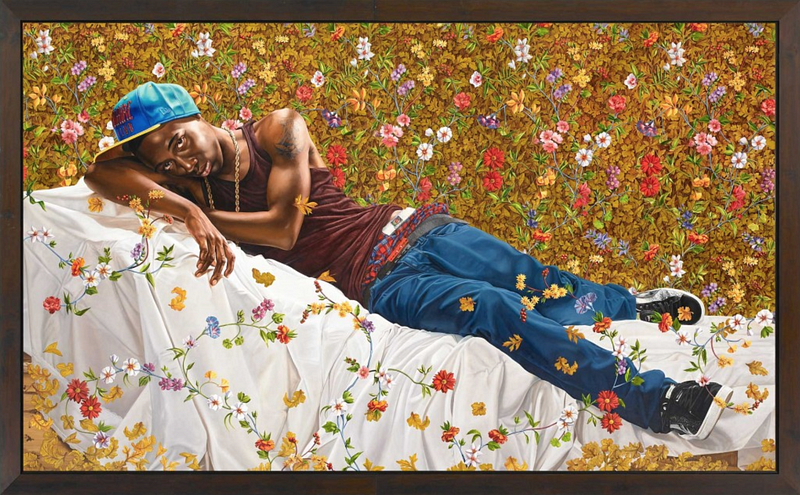

Morpheus shows up in the dreams of Alcyone in the form of her husband Ceyx, to tell her that Ceyx has died in a shipwreck. But he’s not the only shapeshifter in Book 11: the goddess Thetis, the mother of Achilles, also makes a dramatic appearance. And the famous King Midas of the unfortunately metamorphic touch appears as well. This is all very well-timed, because at this point in the semester, I wanted to talk to my class about classical receptions. I highlighted later works or sections of art and literature based on Ovid’s poem. They pick up pieces of Ovid’s material, reflect them through a new author’s perspective and purposes, and transform them into something new yet familiar. Anything from illustrations in editions of the text to Clash of the Titans can offer an interpretation or metamorphosis of Ovid. Kehinde Wiley’s Morpheus shows us the god of dreams in just the latest of his infinite forms, the stuff of dreams for a later generation. In studying receptions like this one, we learn a lot more about what we ourselves saw — or didn’t see — in Ovid’s text. So many readers have loved this text, and classical receptions start new discussions with fellow fans, of whatever era or culture.

Book 11 begins with the death of Orpheus. A crazed band of Bacchants murder and dismember Orpheus in their fury at his misogyny, but at least Orpheus is reunited with Eurydice in the Underworld. This is a bit of a Book 3 redux, a repeat of the Theban cycle of Semele, Pentheus, and the Minyades of Book 4. Bacchus turns the women into oak trees and returns to Asia, where his old fellow reveler and foster-father Silenus wanders off and stumbles upon King Midas. Midas returns Silenus to Bacchus, who is so grateful that he offers Midas to fulfill any wish. The foolish king wishes that everything he touches will be turned to gold.

His mind

Could scarcely grasp his hopes — all things were golden,

Or would be, at his will! A happy man,

He watched his servants set a table before him

With bread and meat. He touched the gift of Ceres

And found it stiff and hard; he tried to bite

The meat with hungry teeth, and where the teeth

Touched food they seemed to touch on golden ingots.

He mingled water with the wine of Bacchus;

It was molten gold that trickled through his jaws.

Midas, astonished at his new misfortune,

Rich man and poor man, tries to flee his riches,

Hating the favor he had lately prayed for.

No food relieves his hunger; his throat is dry

With burning thirst; he is tortured, as he should be,

By the hateful gold. Lifting his hands to Heaven,

He cries: ‘Forgive me father! I have sinned.

Have mercy upon me, save me from this loss

That looks so much like gain!’ (11.117–35, Humphries translation)

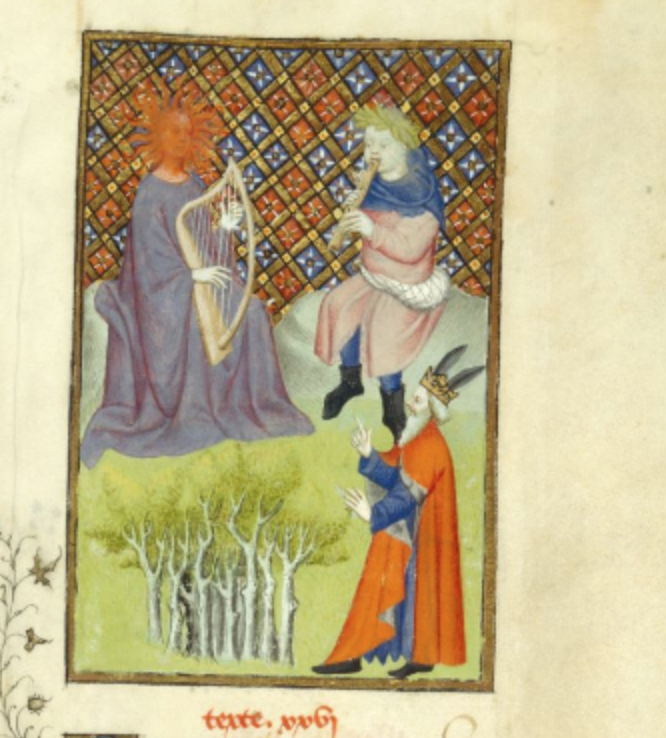

This is pretty tame, as King Midas stories go; in other versions he lays a trap for Silenus to extort his wish, and turns his own daughter into gold before he manages to free himself from the “blessing” of Bacchus. In Ovid’s version, though, the king may learn to be careful what you wish for, but has not learned to be any more prudent. He ends up judging a music contest between Pan and Apollo, and chooses the wrong victor.

Pan made music

On the rustic reeds, and the barbaric song

Delighted Midas utterly — it so happened

Midas was listening. Then old Timolus

Turned to Apollo, and his forests followed

As he inclined his gaze. Apollo’s hair,

Golden, was wreathed with laurel of Parnassus,

His mantle, dipped in Tyrian crimson, swept

Along the ground. His lyre, inlaid with jewels,

With Indian ivory, his left hand held;

His right hand held the plectrum. You could tell

The artist from his bearing. With his thumb

He plucked the strings, and charmed by that sweet music,

Timolus ordered Pan to lower his reeds,

Submissive to the lyre, and all approved

The judgment of the holy god of the mountain,

All except Midas, who began to argue,

Calling it most unfair. Such stupid ears,

Apollo thought, were surely less than human,

And so he made them longer, stuffed them full

Of gray and shaggy hair, and made their base

Unstable, giving them the power of motion.

The rest of him was human; this one feature

Alone was punished, and he wore the ears

Of the slow-going jackass. (11.164–80)

Having avenged himself, Apollo wanders off to Troy and finds King Laomedon building the new city’s walls. Apollo and Neptune chip in, but when the king refuses to pay them for their labor, Neptune drowns the city and demands the king’s daughter, Hesione, in return, Andromeda-style. Hercules saves her, but gets into a fight with tricky Laomedon himself and sacks the city with his buddies Telamon and Peleus, the sons of Aeacus. (A little odd, since Hercules’ death was related in excruciating detail in Book 9.)

Now we’re getting into some well-trodden epic territory: we’ve arrived at the walls of Troy and the prelude to the Trojan War. Ovid’s poem is an epic, after all, and he’s already run through versions of the Theban cycle and the Argonautica, both the subjects of earlier epic. But Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are different. Homer was the be-all and end-all, the origin of all literary genres, according to classical poets. (Modern scholars don’t believe that there was one poet “Homer” who composed and wrote down both poems.) It takes real nerve to go up against Homer in his own genre. Classical receptions take chutzpah.

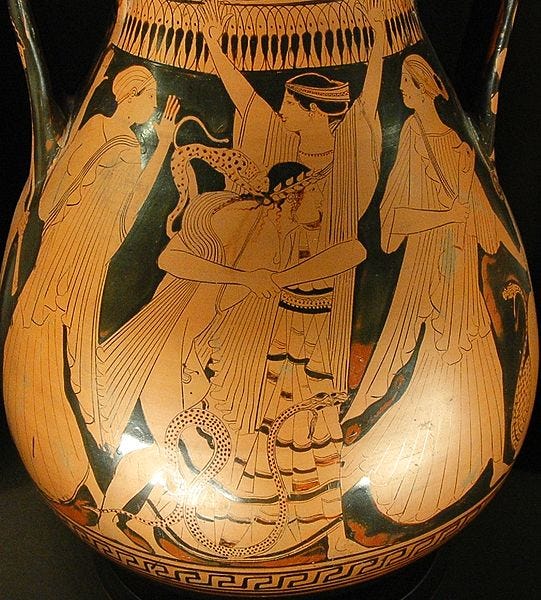

Appropriately enough, Ovid seizes on the part of this story that’s all about metamorphosis: the “marriage” of Peleus and Thetis. Jove has his eye on the sea goddess Thetis, but thinks better of it when the shape-shifter Proteus tells Thetis that her son will surpass his father. Jove sends his grandson Peleus to marry her instead — but he has to catch her first.

And Peleus found her there, and seized her, sleeping,

Pleaded, and had refusal for his answer,

And would have turned to force, but she escaped him

With those old arts she knew; she was a bird,

He held the bird; she was a tree, he clung

Holding the trunk; she was a spotted tigress,

And he let go, and turned and prayed to the sea-gods,

Pouring them wine, offering the smoke of incense,

Entrails of sheep, till the Carpathian sea-god

Rose from his depths with counsel: ‘You will have her

Some day, O son of Aeacus: you must catch her

Asleep in that deep cave, and bind her, sleeping,

With every kind of noose and snare, and hold her,

Hold her, for all the hundred lies she tells you

With changing form, till she becomes again

What once she was.’ (11.238–53)

Once Peleus has captured Thetis, we leave the Trojan War story for awhile and go with Peleus to Trachis. Peleus has been exiled from Aegina for murdering his brother Phocus (a minor character from Book 7), and King Ceyx, the son of the Morning Star (a.k.a. Lucifer, the “light-bringer”), takes him in and tells him the story of his own brother, Daedalion. Daedalion’s daughter (mother of Autolycus, Odysseus’ maternal grandfather) boasts that she is more beautiful than Diana, who kills her. Daedalion goes wild with grief, as his brother Ceyx describes:

‘My sorrow

Was like a father’s, sharing my brother’s grief,

And I said words to comfort him. He heard them

As a rock hears the murmur of the ocean,

And all the answer he gave was lamentation

Until he saw the funeral pyre burning,

Then he dashed toward the fire — four times he tried

To join his daughter, and four times was driven

Back from the pyre, and rushed, the way a bullock

Rushes with hornets at his neck and shoulders,

Where no path lay, and in his rush he seemed

Swifter than any human could be.

You would think his feet had wings. He fled us all,

Swift in his longing for death, and gained Parnassus

And flung himself from that high cliff. Apollo

Took pity on him, held him high in air

On sudden wings, made him a bird, and gave him

Hooked beak, hooked talons, but he left him still

His old-time fierceness, greater than his body,

And now he is a hawk, vindictive judge,

With charity to none, for, having suffered,

He must make others suffer.’ (11.327–48)

In Trachis, we get another tragic story, of Ceyx and Alcyone. Alcyone is terrified that her beloved husband will meet a premature end, first hunting with Peleus and then when he embarks on a sea voyage to consult an oracle. Alcyone, the daughter of Aeolus, the god of the winds, is only too familiar with shipwrecks, and begs her husband to go by land. Alcyone proves prescient: Ceyx is caught in a cataclysmic storm. Like Odysseus or Aeneas, one of his shipmates envies those who die on land and can be buried by their families; Ceyx only thinks of Alcyone. But unlike his epic predecessors, Ceyx does not survive the storm. Alcyone’s prayers, meanwhile, are heard by Juno — she doesn’t bother to protect Ceyx, but she does send a dream to Alcyone to tell her what has happened, hence the entrance of the god of Sleep, and his son Morpheus.

Here the god is lying,

Dissolved in slumber. And around him lie,

In various forms, the unsubstantial dreams,

As numerous as the wheat-ears of the harvest,

The green leaves of the woods, or grains of sand

Along the shore. …

‘O mildest of the gods, most gentle Sleep,

Rest of all things, the spirit’s comforter,

Router of care, O soother and restorer,

Juno sends orders: counterfeit a dream

To go, in the image of King Ceyx, to Trachis,

To make Alcyone see her shipwrecked husband.’…

And Sleep roused Morpheus from his thousand sons,

Best of them all at imitating humans,

Their garb, their gait, their speech, rhythm and gesture.

It is only men he imitates; another

Assumes the form of beast or bird or serpent,

And him the gods call Icelos, but mortals

Call him Phobetor. A third is Phantasos,

Who has a different skill, wears shapes of earth,

Rocks, water, trees, and all inanimate things. (11.612–42)

Alcyone soon finds evidence that her dream was true, and in her grief, she is transformed into a kingfisher. Intermittent “halcyon days” mark her father Aeolus’ mourning, when he keeps the winds from blowing.

And the waves washed the body a little closer

To her great hurt, and as it neared the land,

She knew — it was her husband. ‘Here he is!’

She screamed, and reached out her trembling hands, crying

‘O my poor husband, my dearest, must you come

Home to me so?’ There was a jetty there

To break the onslaught of the rushing ocean.

She ran along it, leaped into the sea —

A marvel that she could — and never fell,

But seemed to skim the surface, like a bird

On new-found wings, and as she flew, unhappy,

Her mouth, a slender bill, made sounds like one

Complaining, sorrowful. She reached the body

Lifeless and still, tried to embrace the limbs

With her new wings, in vain, and tried to kiss

Cold lips with her rough bill. No one could say

Whether Ceyx felt those kisses and responded,

Or whether it was the lift of the waves alone

That made him raise his face. But he had felt them,

And through the pity of the gods, the husband

Became a bird, and joined his wife. (11.724–44)

Ceyx and Alcyone, the pair of kingfishers, have an audience: an old man watches them and recalls another story. Where is he? When is he? The story he tells to close Book 11 is about Aesacus, a half-brother of Hector, a son of Priam, but we haven’t arrived at that generation in Troy yet.

Lest you think that Ovid’s just giving you a mythology textbook, it doesn’t quite all fit together, like a dream. You recognize the place but the details aren’t right. Reality and fantasy get mixed up. Ovid riffs on earlier literature, creating new masterpieces out of old ones to show off his cleverness, to give his listeners the pleasure of recognizing a familiar story in a new form.