Metamorphoses 12: Invulnerability

The Iliad doesn’t tell the whole story of the Trojan War. It tells the story of “The Wrath of Achilles” nine years into that war, and ends…

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

The Iliad doesn’t tell the whole story of the Trojan War. It tells the story of “The Wrath of Achilles” nine years into that war, and ends when Achilles’ wrath has run its course, not with the fall of the city or even the death of Achilles but with the death of his enemy Hector. When Ovid takes on the Trojan War, his emphasis is — predictably — very different. He avoids following in the footsteps of Homer and pays more attention instead to the stories classical Greek tragedians told about Troy: Iphigeneia, Ajax, the Trojan Women enslaved after the war, and Hecuba’s revenge. In Book 12, his sequence of metamorphoses with tragic endings centers around another theme: invulnerability, characters who cannot be wounded with swords or spears. Achilles was said to be invulnerable himself in some versions of the myth, with the famous exception of his heel, but Ovid doesn’t mention that. Instead, Achilles himself encounters two invulnerable warriors, but like him, they turn out to be mortal in the end.

The Trojan War is set in motion when Paris, a prince of Troy, runs off with Helen, queen of Sparta. (You’d think a love poet like Ovid would tell us how they met, or how Helen was born from an egg, but strangely he doesn’t.) Her husband and her brother-in-law, Agamemnon, gather an alliance of Greek kings to go and get her back, but the alliance only makes it as far as the Greek port city of Aulis. There, the winds prevent them from sailing east to Troy. A seer, Calchas, tells Agamemnon that the goddess Diana is causing this adverse wind, and to appease her, the Greeks must sacrifice a human victim: Agamemnon’s own daughter, Iphigeneia.

Virgin blood

Must satisfy the virgin goddess’ anger.

The common cause was stronger than affection,

The king subdued the father; Agamemnon

Led Iphigenia to the solemn altar,

And while she stood there, ready for the offering

Of her chaste blood, and even the priests were weeping,

Diana yielded, veiled their eyes with cloud,

And even while the rites went on, confused

With darkness and the cries of people praying,

Iphigenia was taken, and a deer

Left in her place as victim, so the goddess

Was satisfied; her anger and the ocean’s

Subsided, and the thousand ships responded

To the fresh winds astern and, with much trouble,

Came to the Phrygian shores. (12.29–44)

As the Greeks set sail, news of their intentions reaches Troy via Rumor, another of Ovid’s elaborate personifications:

Here Rumor dwells,

Her palace high upon the mountain-summit,

With countless entrances, thousands on thousands,

And never a door to close them. Day and night

The halls stand open, and the bronze re-echoes,

Repeats all words, redoubles every murmur.

There is no quiet, no silence anywhere,

No uproar either, only the subdued

Murmur of little voices, like the murmur

Of sea-waves heard far-off, or the last rumble

Of thunder dying in the cloud. The halls

Are filled with presences that shift and wander,

Rumors in thousands, lies and truth together,

Confused, confusing. Some fill idle ears

With stories, others go far-off to tell

What they have heard, and every story grows,

And each new teller adds to what he hears.

Here is Credulity, and reckless Error,

Vain Joy, and panic Fear, sudden Sedition,

Whispers that none can trace, and she, their goddess,

Sees all that happens in heaven, on land, on ocean,

Searching the world for news. (12.42–63)

This passage reminded me of Morpheus, from Book 11: like Rumor, he can also take a variety of forms, “presences that shift and wander,” and can be true or false, without a way to tell the difference. They’re tricky, deceitful storytellers and unreliable narrators.

When the Greeks arrive in Troy, Achilles sets his eye on Hector and another great warrior unfamiliar from the Iliad: Cygnus, the son of Neptune. When Achilles’ usual talents prove ineffective against him, he gets a little impostor syndrome and wonders if he’s such a great warrior after all:

Could the spear have lost its point? He looked it over.

No, it was on the shaft. ‘Has my hand weakened,’

He thought, ‘in this one instance? Once I had

Strength enough, surely, when I led the onslaught

Against Lyrnessus’ walls, and made the rivers

Run red with blood, and Telephus, more than once,

Felt my spear’s power and thrust. On this field also

I have made and seen my heaps of slain; my hand

Is strong, as it has been.’ As if he needed

Proof of the past, he flung one spear the more

Straight at Menoetes, and the weapon drove

Through mail and breast, and the dying victim

Came clanging to the ground; from the hot wound

Achilles pulled the spear in wild rejoicing:

‘This is the hand, this is the spear, that brought me

Victory once again, and I shall use them

Against this foe, and the same fate befall him!’

He threw again at Cygnus, and the ash

Went straight, and hit the shoulder, and bounced off

As from a wall. (12.107–25)

Achilles isn’t the only extraordinary, invulnerable demigod in this version of the Trojan War. He figures out a way to kill Cygnus by strangling him, but Neptune transforms him into a swan to allow him to escape. This duel is as close as Ovid gets to narrating a traditional battle scene in the Trojan War, and it’s not traditional at all. In fact, after this duel, we leave the Trojan War altogether. Old King Nestor tells Achilles the story of another war, the war between the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the wedding of Pirithous and Hippodamia. Why narrate a war between humans when you could narrate a battle between humans and centaurs? Nestor’s story is gruesomely detailed, gory in the extreme — it puts Game of Thrones’ Red Wedding to shame.

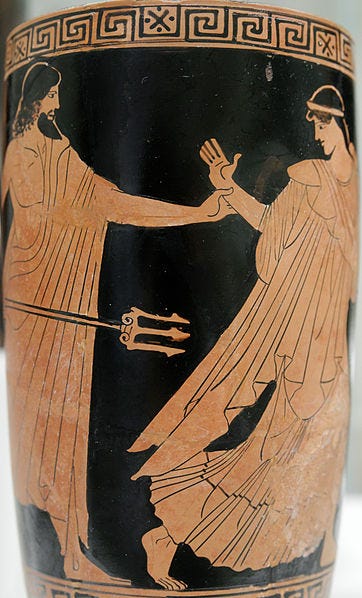

Nestor begins by telling Achilles that Cygnus reminds him of the story of another invulnerable warrior. This one, Caeneus, was born a woman.

Caenis would not consent to any marriage.

She used to walk the lonely shore, and Neptune

(Or so they say) got hold of her one day,

Took her by force, and liked what he had taken

And told the girl: ‘Ask me for anything,

And you shall have it. What do you want the most?’

(That was what people said, at least.) And Caenis

Replied: ‘The wrong you have done me makes me ask

For something most important: that I may never

Again be able to suffer so. I ask you

That I may not be woman; that would be best.’

She spoke the last words with a deeper tone,

The voice might have been a man’s, and it was, truly,

For the deep ocean’s god had given his word

And to it added that no man should hurt her,

That she should never fall by any thrust,

So she, or he, went on his way rejoicing

And spent the years in male pursuits, and traveled

All over Thessaly. (12.197–212)

Caeneus’ invulnerability is the result of Caenis’ vulnerability, and her determination to dissociate herself from that vulnerability, to prevent herself from being the victim of further attacks. If she weren’t a woman, she thinks, she wouldn’t have been a victim. The Ovidian Trojan War seems to support her conclusion: it begins with the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, and it will end with the sacrifice of another young princess, Polyxena. The Metamorphoses in general doesn’t do much to dispel this impression either: not only do the gods rape women over and over in the poem, but it is often the women who are punished for it. Neptune’s rape of Medusa in Book 4 results in her transformation into a snake-haired monster, to take one apposite example. Caenis is just lucky that she gets to choose what happens to her. That she goes away “rejoicing” is an extremely disturbing comment on femininity in the world of myth. Almost every student in my class brought up this myth in their assignments this week.

And as it turns out, Caeneus’ sex does not protect him from attacks. In the battle with the Centaurs, Caeneus’ invulnerability is put to the test by the taunting misogynist Latreus:

‘Am I to stand this woman,

This Caenis? Woman you are, and always will be,

Caenis, to me; does not your birth remind you

Of what you used to be, at what a cost

You gained this lying semblance of a man?

Remember, daughter, all that you have suffered,

Go back to your distaff and your weaving baskets,

Go turn the wheel, go spin the wool; leave arms

To men, where they belong!’ Across his boasting

The spear of Caeneus flew, plowed up his side

Where horse met man, and mad with pain he struck

With his long pike full in the face of Caeneus,

But the pike jumped back, the way a hailstone bounces

From a tin roof, or a pebble from a drum.(12.468–81)

Like Achilles, after this initial frustration, the Centaurs finally find a way to kill Caeneus: they bury him under a hail of tree trunks, until he either dies or is transformed into a bird (Nestor isn’t sure).

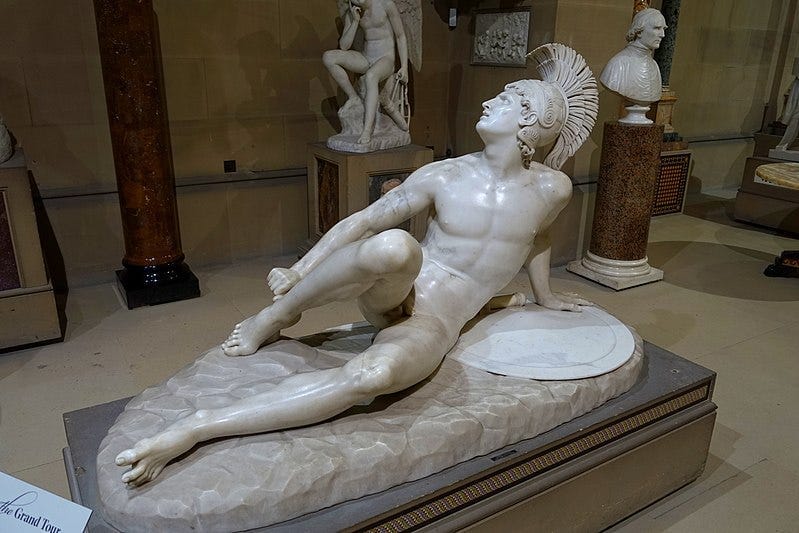

Somewhere in all this, we’ve skipped almost to the end of the Trojan War. Neptune gets his revenge on Achilles for killing Cygnus: he sends Apollo to bring about Achilles’ death.

As very god

He spoke rebuking Paris: ‘Why waste arrows

On common rabble? If you care at all

For vengeance, for your people, hit Achilles,

Revenge your murdered brothers!’ and he pointed

To where Achilles stood, his bright sword reaping

The Trojan ranks, and Apollo swung the bow,

Guided the hand of Paris, and old Priam

Could almost smile for the first time since Hector

Had been brought low. So the great conqueror,

Conqueror of the mightiest, was conquered

By coward and seducer. How much better

To have been killed outright by a manly woman

Than womanish man, to have the Amazon,

Penthesilea, whom he slew, been victor

With her great battle-axe! So now Achilles,

The Terror of Troy, the ornament and bulwark

Of the Greek name, the great invincible captain,

Was burned. The same god armed him and consumed him.

Now he is only dust, and of Achilles,

Of all that might, nothing, or almost nothing,

Remains, a pitiful handful, scarce sufficient

To stop a hole to keep the wind away.

But still his glory lives, and in that glory

He fills the whole world. This is the measure

To judge him by, in this the son of Peleus

Is still himself. (12.597-621)

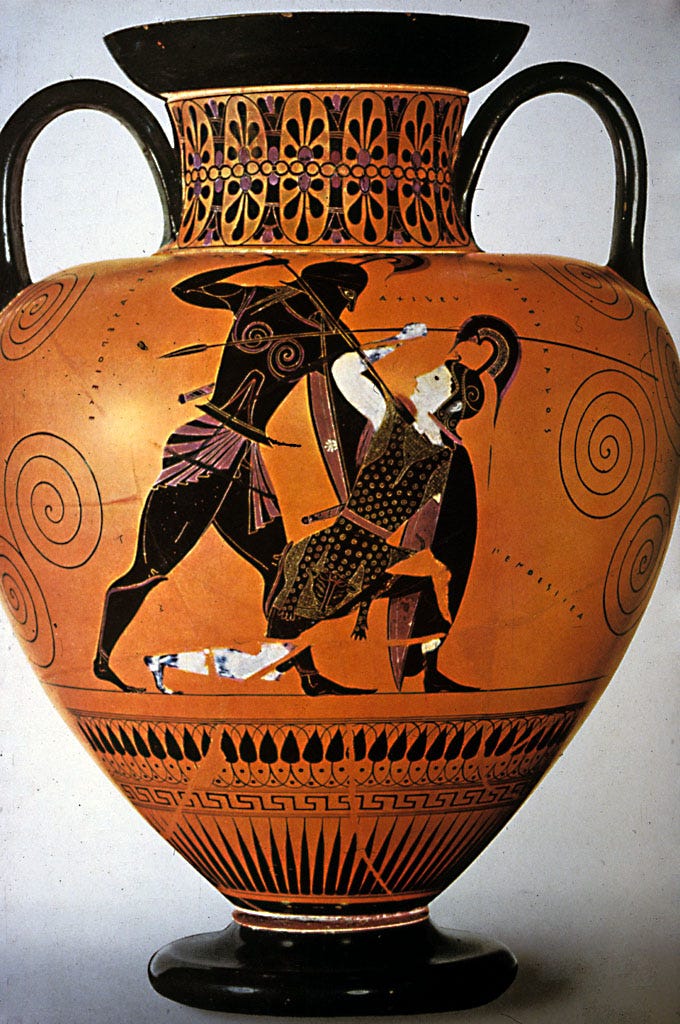

Ovid refers to Penthesilea, the Amazon and “manly woman” killed by Achilles in a duel, at the very moment when he falls in love with her. It almost would have made a better story, he says, if Achilles had died then instead — but the Trojan War isn’t infinitely amorphous after all. He makes a point of the emasculating indignity of Achilles’ death, almost taunting him as Latreus taunted Caeneus. War epic is an arena in which masculinity is often celebrated, but not the way Ovid tells it.

Ovid says that Achilles earned immortal glory that outlived him: in a poem about metamorphoses, Achilles’ glory is notably unchanged, and allows him to live on forever in the same form. That’s the part of him that’s really invulnerable. But Ovid’s Trojan War begins not with the inspiration of a Muse, but with Rumor, the unreliable narrator who amplifies and spreads falsehoods mixed with truth. Are we supposed to believe in the greatness of Achilles or not? As stories pass through the Rumor mill, “Every story grows, / And each new teller adds to what he hears” — just the way Ovid has embellished and added to the myths he reports. Rumor’s lurking presence calls heroic glory into question, just in time for the end of the poem, where Ovid will begin to tell the story of Rome’s own heroes and rulers, down to his own time.