Metamorphoses 13: A courtroom drama

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

When I’m out of the classroom and doing research, I specialize in the political rhetoric of the late Roman republic, a generation before Ovid. So I got really excited about the long paired speeches in Book 13 of the Metamorphoses, as Ajax and Ulysses (a.k.a. Odysseus) each makes his best case as to why he deserves to become the new owner of the armor of Achilles, manufactured by the god Vulcan. Ovid is well-equipped to write great speeches, because (like most upper-class Romans) he was actually trained in rhetoric, but he frustrated his teachers. Seneca the Elder, a rhetoric expert, reports that Ovid found argumentation boring, and that he had the ability but not the desire to exercise self-control when it came to fanciful style (Controversiae 2.2.12). “His oratory never could have seemed like anything but poetry free of meter,” Seneca says — in fact, Ovid borrowed from his own teacher’s mock speech about the Judgment of the Arms of Achilles for this episode in the Metamorphoses (2.2.8).

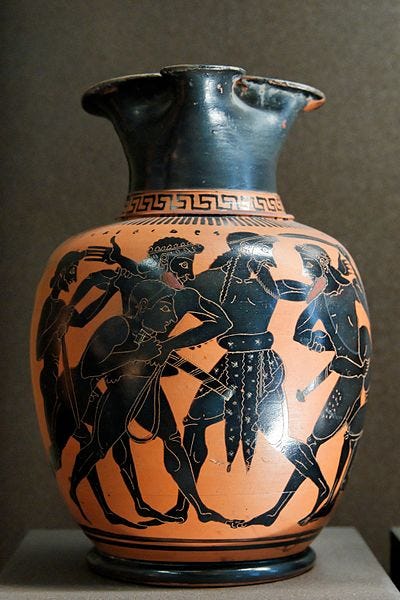

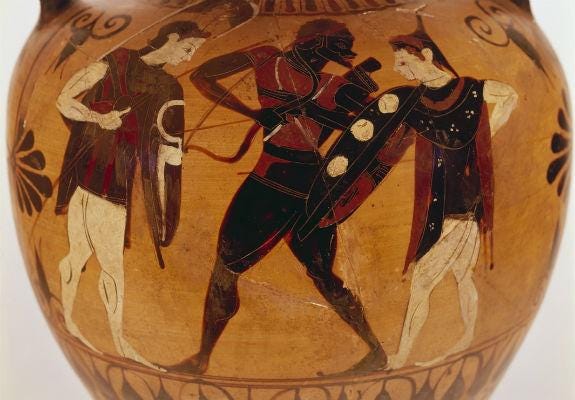

Ajax gets to speak first, and he is enraged that there is any doubt whether he deserves the armor. He was the best warrior among the Greeks — apart from Achilles, of course — and he is even Achilles’ first cousin. What claim does Ulysses have? In making his case, Ajax starts to rehash and relitigate the events of the Trojan War.

Where was he, though, when Hector’s torches threatened

Those very ships? Running away! But I

Stood fast, and drove the fire away. It is safer

To fight with lies than with hands, no doubt of that.

I am no good at speaking, any more

Than he is good at doing. He can beat me

In talking, by as far as I can beat him

In the fierce battle-line. As for my deeds,

O Greeks, I do not think I need to name them,

You have seen them. (13.8–18, Humphries translation)

Ajax argues that his birth is more noble than that of Ulysses, who he claims was the bastard son of the trickster Sisyphus. Ulysses didn’t even want to fight at Troy, Ajax reminds the jury: he pretended to be insane so that he wouldn’t have to leave his wife and infant son in Ithaca. His greatest triumphs, the murder of Dolon and the theft of the sacred Palladium of Troy, were accomplished through treachery at night, not in open battle.

Why give them to this Ithacan, who always

Does things by stealth, always unarmed, relying

On tricks to fool the foe? The helmet’s shine,

The luster of that bright gold, would give away

His hiding-places, and that helmet’s weight

Would be too heavy for him, and the spear

Too much for him to lift, let alone carry!

And that left hand is better at picking pockets

Than holding Achilles’ shield, that great round world.

You are weak enough already, trickster, coward,

Why take on further handicap, a prize

(If — God forbid — the Greeks should give it to you)

That would invite the enemy not to fear you,

But spoil you, rather? With that burden on you,

Your only talent would be gone, the speed

To run away with. And one thing more: your shield

So rarely used in battle has no mark,

No dent upon it; mine has a thousand places

Where spears and darts have struck; I need a new one.

Why talk? What good are words? Let us be seen

In action. (13.102–21)

What can Ulysses possibly say to all this? He gets up to speak but doesn’t make eye contact — in fact, it almost looks like he’s crying, not about Ajax but for the fallen Achilles.

“O Greeks, if what we prayed for, you and I

Together, had been granted, we should have

no question of the heir in this great contest.

Achilles still would have his arms, and we

Would have Achilles. But since he has been taken”

(And here he made a gesture towards his eyes

As if to brush off tears) “by Fate’s injustice,

…Why should there be profit and gain for Ajax

In seeming stupid, as he is? And why

Should I be hurt because I used my wits

Always for your advantage? If I speak

With any eloquence and plead my cause

As I have pleaded yours, envy me not

My talent; a man must use what power he has.” (13.126–41)

Ovid’s rhetoric teachers would call this a captatio benevolentiae, a “capturing of goodwill” from the audience, and an insinuatio, a sneaky introduction to a speech where you don’t come right out and make your argument, but start with a hesitant, almost defeatist show of doubt. Ulysses then starts to debunk Ajax’s arguments: actually, his father — Laertes, not Sisyphus — was descended from Jove just like Ajax (and so are lots of other heroes, for that matter). Actually, it was thanks to Ulysses that Achilles himself fought at Troy, because Achilles tried to use trickery to avoid the war too, dressing up as a girl on Scyros to hide. If you think about it, then, everything that Achilles did at Troy is really a credit to Ulysses.

“Your arm is useful in the wars; your wits

Need mine to guide them. You are strong, and brainless;

I think about the future. You can fight,

We set the time for fighting, Agamemnon

And I, Ulysses. Only in the body

Are you worth anything, but I have mind,

Sense, and intelligence. As a ship’s captain

Is better than a rower, as a leader

Is greater than his soldier, so do I

Outrank you, Ajax; in my make-up knowledge

Governs brute force, and therein lies my talent.

…

Now, by our common hopes, by those doomed walls,

By the gods whom I have taken from that city,

By any further need we have of wisdom,

Of boldness, of recovery from danger,

By anything you feel may still be lacking

To bring Troy down, remember me, reward me!

Or, if you do not give those arms to me, then give them

To her!” He gestured to Minerva’s image.

So they were moved; what eloquence could do

Was evident; the eloquent bore off

The brave man’s arms. (13.359-85)

Eloquence and cleverness win out over bravery; Ulysses doesn’t even bother trying to argue that he’s as strong as Ajax in battle, but instead convinces the jury that brute force isn’t as valuable as intelligence. Ulysses ends on an ominous note: the city of Troy hasn’t fallen yet, and his jury still needs their resident mastermind. If they insult him now and decide against him, they might pay for it later. His greatest ploy, the Trojan Horse, is yet to come. Ulysses gets the arms, and Ajax, in a rage, commits suicide.

This is starting to remind me of the cold and calculating emperor Augustus: he wasn’t much good in a fight (his loyal lieutenant Agrippa handled the practical stuff) but he was a brilliant political operator. He claimed to be the successor to Julius Caesar, his uncle-turned-adopted father, staking that claim against Caesar’s right-hand man Mark Antony. Antony, portrayed as a bit of a thug by Cicero and Augustus, committed suicide like Ajax. So did his lover Cleopatra — and women are casualties in Ovid’s narrative too, as we’ll see.

Even after his death, Achilles continues to rack up a death toll, and after the death of Ajax he demands a human sacrifice as well: Polyxena, the youngest daughter of Hecuba and Priam of Troy. Ovid’s Trojan War began with the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, so we’ve come full circle in some way. Polyxena also recalls the end of the Iliad, when human sacrifices to the shade of Patroclus also marked an ending. As Polyxena goes unflinching to the altar, she asks that her mother not be made to pay a ransom for her body, as Priam was forced to ransom his son Hector’s body from Achilles. As in the Iliad, we see the Trojan women in mourning, for Polyxena and all the others they have lost.

Polyxena’s mother, Queen Hecuba, laments for Polyxena and wanders down to the beach, where she finds the body of her youngest son, Polydorus, who she thought was safe in the court of King Polymestor. With that, Hecuba finally reaches her breaking point.

The Trojan women shrieked, but Hecuba

Made never a sound; like a hard rock, she stood there,

Looked at the ground, or turned her face to Heaven,

Looked at her son, who lay there dead, and studied

His wounds, his wounds, and in that study armored

Herself, equipped her passion. In that rage

She towered, a queen again, whose whole employment

Spelled out the images of fitting vengeance.

As, when her suckling cub is stolen from her,

A lioness goes raging, tracking down

The unseen enemy, so Hecuba,

In grief and anger, with her years forgotten,

Her aim remembered, went to Polymestor…

She watched him glowering,

And with this perjury her wrath boiled over;

She called the captive women to her, grabbed him,

Dug fingers into his lying eyes, dug out

The eyeballs from their sockets, and kept digging,

In manic fury, with bloody fingers, scooping

The hollows where the eyes had been. The Thracians,

In fury at her deed, came after her

With spears and stones, but she,

Snarling and growling, chased the stones and bit them,

Opened her mouth for words, but what came out

Was barking. (13.540–73)

Ovid’s Trojan War ends with another mother’s grief: the goddess of the Dawn, Aurora, is mourning her son, Memnon, a hero of Ethiopia who was killed by Achilles. Memnon’s death, like that of Achilles, is commemorated with further slaughter: birds known as the Daughters of Memnon fight to the death every year to honor their father.

With that, we leave Troy with Aeneas , moving toward Vergil’s territory — but his epic journey is almost immediately interrupted by the story of the similarly-named Anius (very funny, Ovid), and then by the story of Polyphemus and Galatea. Polyphemus is the Cyclops of the Odyssey, who captures and eats several of Odysseus’ fellow sailors before Odysseus blinds his one eye and escapes. Before all that, we learn from Ovid, Polyphemus was a prosperous shepherd in love with a sea nymph, Galatea. She is not interested in a shaggy, one-eyed giant — in fact, she is in love with someone else, Acis. I took this opportunity to have my class compare translations of the Latin, because Polyphemus’ love song for Galatea is very eccentric and very funny. Here’s a rendition by Jamie McKendrick, a British poet and translator, from the collection After Ovid (1996).

So who says I’m that gruesome? I saw myself

in a blue pool today and thought — just look

at the size of him will you? Even Jove

who doesn’t exist could never be bigger.

does being hairy have to mean I’m vile?

Would you want a bald hound or horse, or a bird

without feathers? And if it’s my one eye,

my unaccompanied eye, that bugs you what about

the sun? Two of them up there and we’d be flayed.

My eye grows on a single stem and follows

only you with its one shaft of devotion.

As for the muck on me, the stink, I’ll scrub

myself with pumice every night before

we touch. Every night to touch you! O

Galatea, drop that skinny runt of an Acis

or let me at him and I’ll tear his limbs

off his hairless trunk and fry them in Etna

whose channels of sulphur and blue fire

are coursing through my veins for love of you.

A love that scalds me and stops me working.

Take a look at my neglected flock. Entire fleets

pass by unscathed as if I were a lighthouse.

I just forget to wreck them. My whole life

is in arrears, in ruins like a great city

turned to burnt earth and swamps and column stumps

while all you do is quiver with disgust

at my offers and take to your exquisite heels

before I can quieten down my heartbeat

enough to speak let alone find the right words,

soft words, to let me creep closer…

Polyphemus’ jealousy boils over and he kills Acis by throwing a boulder at him (just as he will attack Odysseus), but Acis is transformed into a god, Glaucus.

As a rhetorician, Polyphemus is more of an Ajax than a Ulysses, and he doesn’t manage to win over his audience. He can’t find “soft words” to insinuate himself into Galatea’s good graces, and turns instead to threats of violence. As Book 14 ends, we get another failed speech: Glaucus, the sea god Acis became, appealing to his beloved nymph Scylla, who turns him down. This is all by way of origin story to explain how Scylla became a monster that attacked Ulysses’ ship in the Odyssey, but for that, we have to wait for Book 14. The consequences of failed speech are dire in Book 13: Ajax’s suicide, Polyphemus’ attack on Acis, Hecuba’s transformation from screaming to barking in reaction to Polymestor’s lies. Ovid’s experience as both an orator-in-training and a love poet comes into play in Book 13. Ulysses himself would have been impressed.