Metamorphoses 14: Circe

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

When Madeline Miller’s novel Circe came out in 2018, I put it on my list of things to read — but I wasn’t sure I’d like it. Sometimes, reading novels based on classical literature feels like work to me (a real downside of my profession). Sometimes I get annoyed that it’s not how I would tell the story, or that my favorite part got left out. In the case of Circe, she’s such an interesting character who pops up in so many myths from the ancient world. Book 14 of the Metamorphoses wanders through many of those stories, and Circe is not the heroine in any of them — in fact, she’s the villain, the wicked witch.

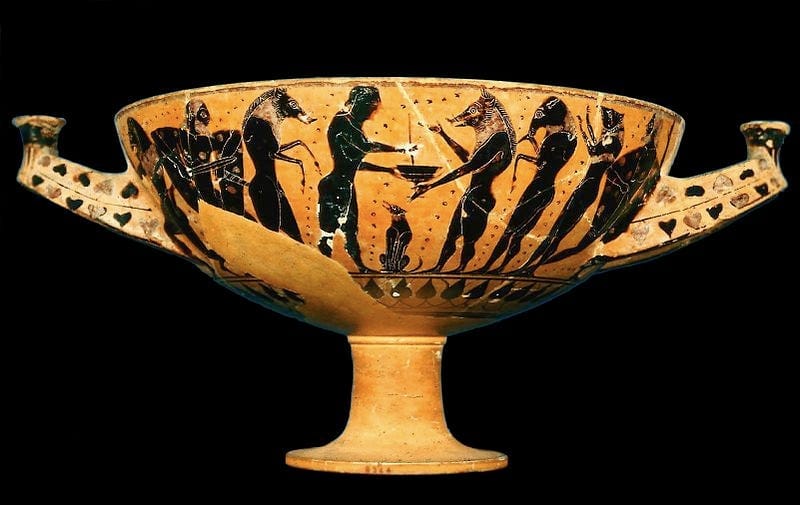

Book 13 ended with the transformation of Galatea’s lover Acis into Glaucus, a sea god, after he is killed by the cyclops Polyphemus. Glaucus has evidently moved on from Galatea to Scylla, another beautiful sea nymph, and goes to the witch Circe for a love charm. Circe, however, is not interested in the role of matchmaker.

‘I, goddess though I am,

The daughter of the shining Sun, the mistress

Of charms and herbs, beg to be yours. Scorn her

Who looks upon you with scorn, repay with love

The one who loves you, and so repay us both.’

But Glaucus answered: ‘Leaves will grow on the sea,

And sea-weed flourish on the mountain-tops,

Before I change my love, while Scylla lives.’

Circe was not angry; she could not harm the god,

And would not harm the god, because she loved him,

And turned her wrath on her successful rival.

Offended, hurt, she crushed together herbs

Whose juices had a dreadful power, and, singing

Spells she had learned from Hecate, she mixed them.

…And Circe dyed this pool with bitter poisons,

Poured liquids brewed from evil roots, and murmured,

With lips well-skilled in magic, and thrice nine times,

A charm, obscure with labyrinthine language.

There Scylla came; she waded into the water,

Waist-deep, and suddenly saw her loins disfigured

With barking monsters, and at first she could not

Believe that these were parts of her own body.

She tried to drive them off, the barking creatures,

And flees in panic, but what she runs away from

She still takes with her…(14.36–65)

Thus is born Scylla, the monstrous creature who devours several of Odysseus’ sailors — in revenge, Ovid says, against Odysseus’ lover Circe. His Circe is jealous and cruel, venting her anger at a man on an innocent woman. A man’s preference is framed as a competition among women (a trope common not only in literature but in reality TV), and women only interact with each other in a sort of ongoing beauty contest. All Scylla did was reject Glaucus, so to call her a “successful rival” is a bit of a stretch.

Circe goes through exactly the same sequence with another man, Picus, a king in Italy who is married to his beloved, Canens, a singer so gifted that she could charm animals and rocks like Orpheus. Circe lures Picus with a phantom boar and gives him a speech very similar to what she’d said to Glaucus, but Picus, too, rejects her. She turns Picus into a woodpecker and his hunting companions into other animals, leaving the grieving Canens to wither away until only her voice remained. Picus, a figure of Roman legend rather than Greek, figures briefly in Ursula LeGuin’s excellent novel Lavinia, about Aeneas’ arrival from the point of view from the Italian woman he eventually married, Lavinia.

In the meantime, Circe also plays hostess to Ulysses and his men, who land on her island unaware of the danger she poses.

‘We came to Circe’s city, and she stood there

Within her courts, and a thousand wolves and bears

And lionesses met us, and we feared them —

For no good reason, for, it seemed, they would not

Make even a single scratch upon our bodies.

They even wagged their tails, and fawned upon us

As we went on, until the serving-women

Led us through halls of marble to their mistress.

She sat there on her throne, in shining robes,

With golden mantle, and the place was lovely,

And nymphs and nereids were waiting on her,

Carding no fleece, spinning no wool, but only

Sorting out plants, arranging, from confusion,

In separate baskets, the bright-colored flowers,

The different herbs. She told them what to do,

Knew what each leaf was for, which ones would blend,

Weighing her simples. When she saw us coming,

She gave us welcome, and smiled upon us…’ (14.255–70)

Before they know it, Ulysses’ men have been turned into pigs. Madeline Miller’s riff on this episode is very witty, and I shared a video of her reading a part of it with my students. Her Circe is very much an herbalist as well as a sorceress. The harm she does to other women is recounted in the novel, but I think her character evolves in interesting ways beyond that (I won’t spoil anything!).

Circe’s misadventures with Odysseus and Picus are narrated by Macareus, one of Odysseus’ sailors, who opted out of further adventures with Odysseus to stay in Italy. He runs into Aeneas, who has just arrived in Italy from Troy, and another of Odysseus’ sailors, Achaemenides, who was left behind when Odysseus fled the island of the Cyclops and was picked up by Aeneas later. Epics collide in Ovid’s poem, and we see events of Homer’s Odyssey and Vergil’s Aeneid through the eyes of minor characters. Aeneas himself visits the Underworld in Cumae (near Naples) with the guidance of the Sibyl, and hears her story of transformation.

Sighing, she answered: ‘I am not a goddess:

Never consider any mortal woman

Worthy of holy incense. Still, I would not

Leave you in ignorance; I once was offered

Eternal life, if I had let Apollo

Take me, still virgin. While he still was hopeful,

Seeking to bend my will with gifts, he told me

Choose what you will, O maid, and you shall have it.

I pointed to a heap of sand and uttered

The foolish prayer that my years might be as many

As there were sand-grains in that mound. I should have

Asked that those years should be forever young,

But I forgot. He granted me the years,

And promised endless youth if he could have me,

But I refused Apollo, and no man

Has ever had me. Now my happier days

Are gone, and sick old age comes tottering on,

And this I must endure, for a long time.

I am seven hundred years of age; I have

Three hundred still to go, before I equal

The tally of those grains of sand. The time

Will come when I shall shrivel to almost nothing,

Weigh almost nothing, when no one, seeing me,

Would ever think a god had found me lovely. (14.128–50)

The Cumaean Sibyl, a Roman prophet, figures more prominently in Christian art than one might expect, including Michelangelo’s rendering of her on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. According to Vergil’s Fourth Eclogue (written around 39 BCE), the Cumaean Sibyl foretold the birth of a child which would mark the beginning of a new Golden Age. This plays into the classical trope of the Golden Age of Augustus, but Christian authors saw it as a prophecy about the birth of Jesus Christ.

The events of Aeneid 6–12, Aeneas’ arrival in Italy and war with the Italian king Turnus, are reduced to a few lines per book, with the exception of Diomedes’ voyage to Italy and one vividly described metamorphosis when the Phrygian goddess Cybele appears to save Aeneas’ ships from burning:

Cybele, holy mother, knew those ships

Had come from Ida’s summit, and remembered.

Her cymbals clashed in the air, and music shrilled

From boxwood flutes, and drawn by lions she came

Riding the yielding air. ‘In vain, O Turnus,

You hurl those brands!’ she cried. ‘I shall save those vessels

Born in my holy groves!’ And while she spoke

Rain followed after thunder, and bouncing hail,

And the winds worked confusion over the waters,

Wild dissonance in the air. The cables sundered,

The ships dove under water, and their wood softened,

Turned into flesh, the prows were heads, the oars

Were toes and swimming legs: what had been body

Was body still, and the deep keel was backbone,

Rigging was hair, and sail-yards arms, but still

They kept their sea-green color, and as naiads

Went playing through the waves they used to fear,

Daughters of mountains they have long forgotten.

But they recalled the perils of the deep,

Their sufferings by sea, and speed the voyage

For storm-tossed ships, save those that carry Grecians.

For they remember Troy and her disaster… (14.534–55)

Aeneas and the Trojans win the war, and he marries the Latin princess Lavinia. As his life draws to a close, his mother Venus intercedes with Jove: isn’t it enough that her son has already been to the Underworld once?

Jove spoke in answer:

‘You are worthy of Heaven’s gift, you both are worthy,

You and your son. Receive what you have asked for.’

Venus rejoiced, gave thanks to Jove, soared high

Through the light air, borne by her doves, and came

To the Laurentian coast, where, through the beds

Of sheltering reeds, Numicius winds his river

To the salt sea. She bade him purge Aeneas

Of all his mortal body, bear it down

In silence to the ocean; he obeyed

And with his waters purified Aeneas

Of all his human dross, but what was best

Remained forever with him, and his mother

Sprinkled his body with a fragrant ointment,

And touched his lips with nectar and ambrosia,

Made him a god, one whom the Roman people

Call Indiges, the Native-Born, and honor

Is paid his temple now, and sacrifice. (14.595–609)

Like Hercules in Book 9, Aeneas undergoes apotheosis, his mortal part burned away to reveal his immortal soul. As the Sibyl told Aeneas, “Every path lies open / To virtue” (14.113–4). At the end of Book 14, Romulus, too, the descendant of Aeneas, becomes a god, along with his wife. Romulus’ father Mars appeals to Jove to deify his son, just as Venus did. This is all leading up to Book 15, when Julius Caesar, who traced his family tree back through Romulus to Aeneas and Venus, will become a god as well.

Before we get there, though, we come back down from heaven to earth, to humble agricultural and fertility gods of Rome and Italy. In Book 14, just where we might expect to find the birth of Romulus and Remus from Mars and Ilia, we get Vertumnus and Pomona instead. We often think of Roman mythology as merely Greek mythology with Latin names tacked on, but the Romans did have their own myths — they just didn’t write very much literature about them that survives today. In this tale of local Italian mythology, it’s male gods competing for the attention of a nymph, Pomona.

Gardens and fruit were all her care; no other

Was ever more skilled or diligent. Woods and rivers

Were nothing to her, only the fields, the branches

Bearing the prosperous fruits. She bore no javelin,

But the curved pruning-hook, to trim the branches,

Check too luxuriant growth, or make incision

For the engrafted twig to thrive and grow in.

She would not let them thirst: the flowing waters

Poured down to the roots. This was her love, her passion,

Venus was nothing to her, but she feared

The violence of the rustics, kept men off

From her closed orchard. Many tried to win her,

Thinking of every way, young dancing Satyrs,

Pans with their horns disguised with pine, Silenus,

Who was always younger than his years, Priapus,

The god who scares off thieves, either with sickle

Or something else he carries. And Vertumnus

Surpassed them all in love, and fared no better.

How often he used to come, dressed as a reaper,

Bringing her grain in baskets, and he looked

The very image of a reaper. Often

He would come with hay around his ears and temples,

Fresh come, or so it seemed, from swathe and windrow,

Or he would have an ox-goad in his hand,

And you would swear he had just unyoked his cattle.

… So, often,

In one guise or another, he would find

His way to her, happy to watch her beauty. (14.626-55)

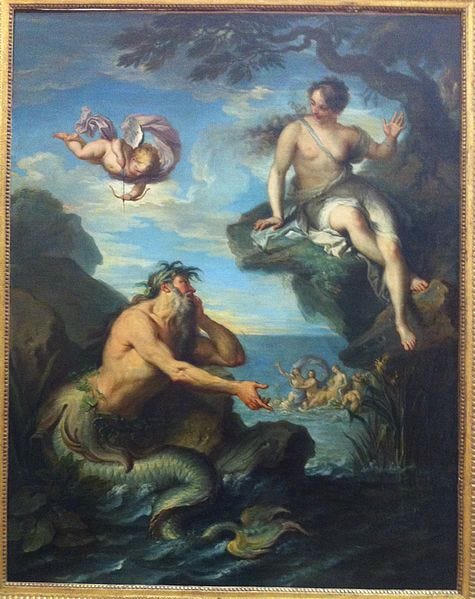

Vertumnus is a shape-shifter, the Roman counterpart to Proteus or Thetis. He turns himself into an old woman and tells Pomona how great that Vertumnus is — and threatens her with the cautionary tale of Anaxarete (a princess of Trojan descent), who was so hard-hearted toward her suitor Iphis that she literally turned to stone. Pomona ignores the old woman, but when Vertumnus gives up his disguises and changes back into his masculine form, Pomona falls in love with him after all.

Authors from Ovid’s own lifetime to Ursula LeGuin and Madeline Miller and their readers have found inspiration in the myths he narrates, and have retold the same stories through new characters or new perspectives — which is exactly what Ovid himself was doing with older myths and literary texts. He includes familiar plots and characters, but passes over familiar elements of each story to zero in on what he finds most interesting: metamorphoses, all things weird and wonderful. I suppose there have always been readers who dislike his account for leaving out their favorite parts or manipulating the stories in the way he does, the same way I get hung up sometimes reading modern novels. Ovid’s poem is not easy to follow, it’s not coherent, and it’s certainly not predictable. Having blogged my way through it, I could probably read it again and come up with an entirely new set of themes and passages and reactions. It is incoherent, but artfully so, and that makes it endlessly rich. I asked my students this week: if you could make any part of the Met. into a movie or TV show, what would it be? What would the trailer look like? And I am dying to watch every one of the trailers they described.