Metamorphoses 15: myths and history

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

On a visit to the Galleria Borghese in Rome, planning for a field trip that never happened (thanks, COVID), I was mystified by the fresco on the ceiling of the Entrance Hall. I thought the warrior (at the bottom) must be Aeneas, who is then represented in the center rising to heaven and meeting Jupiter. A helpful guide told me that in fact, the fresco represented Camillus, a rather less famous Roman hero of the Republic. The figure in the center is Romulus, pleading with Jupiter to aid Camillus. I was skeptical until a little research reminded me that one of the most famous members of the Borghese family was Camillo Borghese, better known as Pope Paul V. I think of Roman mythology through the lens of a Latin professor, but for powerful people and families, Roman mythology and history have always offered a source of personal self-aggrandizement.

In Book 15, Ovid moves from myth into history, up to the death of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, and deploys myth as political propaganda, just as the Borghese family did later. Myth and history aren’t easy to separate in the ancient world; you’ll find epic poems and tragedies about real historical people, and chronicles or genealogies of mythological characters as if they’re real. Aeneas, Romulus, the kings of Rome, and even heroes of the Republic may be legends, or at least mythologized, perhaps with some kernel of truth behind the stories. Roman historians of the Republic had a habit of writing their own ancestors into history as protagonists. Even so, Julius Caesar feels like a real aberration from the rest of the poem, and even the rest of Book 15. The celebration of Caesar uses myth to embellish history, rather than using a loose historical framework to organize myths, as Ovid does in the rest of the poem.

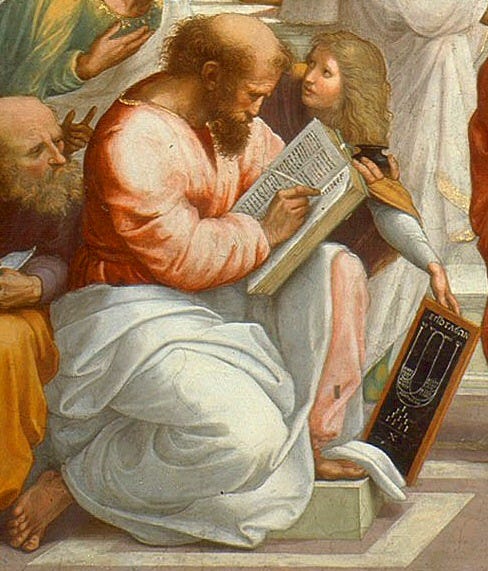

In fact, Book 15 starts with a figure who subverts not only this book but the whole poem: Numa, the second king of Rome, and a devotee of the philosopher Pythagoras. Among other things, Pythagoras believes in the reincarnation of souls in other bodies, and thus argues for vegetarianism so that we do not inadvertently consume another human soul’s body.

‘O mortals,

Dumb in cold fear of death, why do you tremble

At Stygian rivers, shadows, empty names,

The lying stock of poets, and the terrors

Of a false world? I tell you that your bodies

Can never suffer evil, whether fire

Consumes them, or the waste of time. Our souls

Are deathless; always, when they leave our bodies,

They find new dwelling-places. I myself,

I well remember, in the Trojan War

Was Panthous’ son, Euphorbus, and my breast

Once knew the heavy spear of Menelaus.

…All things are always changing,

But nothing dies. The spirit comes and goes,

Is housed wherever it wills, shifts residence

From beasts to men, from men to beasts, but always

It keeps on living. As the pliant wax

Is stamped with new designs, and is no longer

What once it was, but changes form, and still

Is pliant wax, so do I teach that spirit

Is evermore the same, though passing always

To ever-changing bodies. So I warn you,

Lest appetite murder brotherhood, I warn you

By all the priesthood in me, do not exile

What may be kindred souls by evil slaughter.

Blood should not nourish blood.’ (15.155–76)

Numa gives a long speech explaining the world according to Pythagoras — it’s partly inspired by another philosophical epic, Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, which describes the universe according to Epicurean philosophy. “Natural philosophers” were the theoretical physicists of the classical world, speculating about elements, atoms, genetics, meteorology, medicine, and other topics — Pythagoras was especially interested in mathematics (hence his theorem) and what we would call numerology, the magical significance of numbers. Numa, preaching Pythagorean doctrine, tells us that the world is ever-changing, naturally dynamic and ephemeral. Perfect for a poem about metamorphoses — but Numa is not talking about that kind of transformation. His idea of metamorphosis is more realistic and rationalizing, almost like a correction of Ovid.

Our bodies also change. What we have been,

What we now are, we shall not be tomorrow.

There was a time when we were only seed,

Only the hope of men, housed in the womb,

Where Nature shaped us, brought us forth, exposed us

To the void air, and there in light we lay,

Feeble and infant, and we were quadrupeds

Before too long, and after a little wobbled

And pulled ourselves upright, holding a chair,

The side of the crib, and strength grew in us,

And swiftness; youth and middle age went swiftly

Down the long hill towards age, and all our vigor

Came to decline, so Milon, the old wrestler,

Weeps when he sees his arms whose bulging muscles

Were once like Hercules’, and Helen weeps

To see her wrinkles in the looking glass:

Could this old woman ever have been ravished,

Taken twice over? Time devours all things

With envious Age, together. The slow gnawing

Consumes all things, and very, very slowly. (15.214–33)

After Numa’s death, Ovid describes the grief of his wife, the nymph Egeria, and her encounter with the resurrected Athenian prince Hippolytus, who is transformed into an Italian seer. He then launches into the story of another Roman, Cipus, who was shocked one day to find that he had sprouted horns.

No less amazed

Was Cipus, looking at his own reflection

In river water, seeing on his own forehead

Horns jutting out. It might have been illusion,

He thought, some freak or trickery of the water,

And so he raised his fingers to his forehead,

Touched what he saw, believed, stood still, as one

Who halts when homeward bound from some great triumph,

Lifted his hands and eyes to Heaven, crying:

‘O gods, whatever this portent means, if good,

Let it be for my people, but if evil,

May that be mine alone!’ He made an altar

Of the green turf, poured wine and sprinkled incense,

Made offerings of sheep, studied the entrails

For further sign. …One soothsayer

Lifting his eyes to glance at Cipus’ forehead

Where the horns grew, cried out: ‘All hail, O king!

This place and Latium’s citadels bow down

To Cipus; only hasten, enter the gates

That stand wide open, waiting. So the fates

Ordain. If once he is welcomed in the city,

Then Cipus shall be king, and wield the sceptre

With safe and endless sway.’ But Cipus kept

His gaze away, recoiling. ‘May the gods

Avert such destiny! Oh far, far better

I be an exile from my home than ever

King on the Capitol.’ (15.564–89)

The metamorphosis of Cipus has a twist: you might think that becoming a king would be a good thing (especially for Cipus, who is so devoted to his people), but Cipus is horrified by the prophecy. He calls the people together and demands that they prevent him from ever entering the city to fulfill the prophecy, renouncing power and his home to protect his fellow citizens from being his subjects — a kind of slavery, in his view. This sounds like the tale of Cincinnatus, a Roman war hero who was elected dictator but renounced his power as soon as he had defeated Rome’s enemies, so that he could go home to his farm. He serves as an inspirational role model for political leaders of the Roman republic: a civil servant should never desire to keep or increase his power beyond what the people want. But Ovid doesn’t tell us when Cipus lived, under the Republic or the monarchy that preceded it. And isn’t this inconsistent with his extravagant praise of Augustus, whom he describes as an absolute ruler? If Cipus was horrified at the thought of “wielding a sceptre with safe and endless sway,” should Augustus have refused that power too?

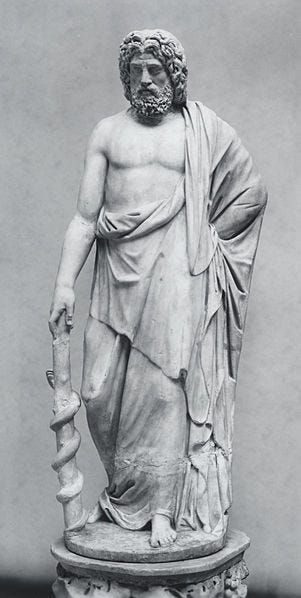

Next comes the introduction of a new god to Rome: Aesculapius, a.k.a. Asclepius, a god of healing and the son of Apollo. In the midst of a plague, the Romans send ambassadors to the oracle of Delphi to plead for divine intervention (has anyone tried that lately?). Apollo instructs them to call upon his son for healing, at his temple in Epidauros. Aesculapius appears to the Romans in a dream to tell them that he will come to Rome with them to stop the plague, and the next day, he appears in the form of a gold-crested snake to travel with them.

The god unfolded

His coils and came in looping curving motion

To his father’s temple on that yellow shore.

And the sea calmed, and once again he left

His father’s altars, a guest there, for a little,

In blood-relationship, and turned, and made a furrow

Along the beach, and the scales rasped like metal,

Until he came to the ship, wound upward, slowly,

The rudder’s length, and rested by the tiller.

He came to Castrum, to the mouth of Tiber,

Lavinium’s holy place, and here the people

Came thronging down to meet him, men and matrons

And maids, the Vestals, and they cried Hosannas,

As the swift ship rode on upstream, and incense

Crackled on altars on both sides the river

And air was fragrant with the smoke of incense

And victim beasts made the knife warm with blood.

He had entered Rome, the capital of the world,

And climbed the mast, and swung his head about

As if to seek his proper habitation.

Just at this point the river breaks and flows,

A double stream, around a mole of land

Men call the Island. Here the serpent-son,

Apollo’s offspring, came to land, put on

His heavenly form again, and to the people

Brough health and end of mourning. The old god

Came to our shrines from foreign lands, but Caesar

Is god in his own city. (15.719-46)

The advent of a healing god transitions directly into Ovid’s praise of Julius Caesar, deified upon his death.

First in war,

And first in peace, victorious, triumphant,

Planner and governor, quick-risen to glory,

The newest star in Heaven, and more than this,

And above all, immortal through his son.

No work, in all of Caesar’s great achievement,

Surpassed this greatness, to have been the father

Of our own Emperor. To have tamed the Britons,

Surrounded by the fortress of their ocean,

To have led a proud victorious armada

Up seven-mouthed Nile, to have added to the empire

Rebel Numidia, Libya, and Pontus

Arrogant with the name of Mithridates,

To have had many triumphs, and deserved

Many more triumphs: this was truly greatness,

Greatness surpassed only by being father

Of one yet greater, one who rules the world

As proof that the immortal gods have given

Rich blessing to the human race, so much so

We cannot think him mortal, our Augustus,

Therefore our Julius must be made a god

To justify his son. (15.746–61)

This is a little cringe-y: modern American readers aren’t used to panegyric (rhetorical praise). Plus, as many of my students pointed out: after neglecting or actively destroying so many lives, NOW the gods are blessing the human race, taking a personal interest in Rome and Caesar? I had asked them if they thought Ovid could be described as imperialistic, and they found his Romanocentrism pretty glaring. The Romans saw their victories as victories for their own native gods over the gods of other places, so that mythology and imperialism are closely joined — or, at least, they can be, when it suits the mythographer. Ovid had been exiled by Augustus, and may well have hoped that this would buy him a ticket back to Rome (it didn’t).

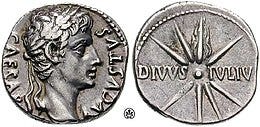

Julius Caesar was assassinated in a meeting of the senate on March 15 (the Ides of March) in 44 BCE. After his death, a comet was seen in the sky, and one observer shouted that it must be the soul of Julius Caesar, ascending into heaven to become a god. An altar to Caesar was set up in the forum, to the consternation of his assassins. His heir, Octavian, capitalized on his newfound status as the son of a god in his coinage and propaganda, later building a temple to the Divine Julius in the Roman forum.

To conclude the Metamorphoses, Ovid writes an invocation to the gods, including Augustus himself (pretty extreme), before meditating on a different kind of immortality.

Jove rules the lofty citadels of Heaven,

The kingdoms of the triple world, but Earth

Acknowledges Augustus. Each is father

As each is lord. O gods, Aeneas’ comrades,

To whom the fire and the sword gave way, I pray you,

And you, O native gods of Italy,

Quirinus, father of Rome, and Mars, the father

Of Rome’s unconquered sire, and Vesta, honored

With Caesar’s household gods, Apollo, tended

With reverence as Vesta is, and Jove,

Whose temple crowns Tarpeia’s rock, O gods,

However many, whom the poet’s longing

May properly invoke, far be the day,

Later than our own era, when Augustus

Shall leave the world he rules, ascend to Heaven,

And there, beyond our presence, hear our prayers!

Now I have done my work. It will endure,

I trust, beyond Jove’s anger, fire and sword,

Beyond Time’s hunger. The day will come, I know,

So let it come, that day which has no power

Save over my body, to end my span of life

Whatever it may be. Still, part of me,

The better part, immortal, will be borne

Above the stars; my name will be remembered

Wherever Roman power rules conquered lands,

I shall be read, and through all centuries,

If prophecies of bards are ever truthful,

I shall be living, always. (15.860–79)

To say that the Metamorphoses culminates with the deification of Julius Caesar isn’t really accurate; it culminates with the immortalization of Ovid’s own poem, above the stars, the real expression of Rome’s power and glory. Pretty grandiose, but I have to admit: we’re still reading him. He doesn’t leave room for the possibility of being translated into other languages after Roman rule ends — but you might say that these translations testify to the continuing power of Rome in another way. The language of classics has been a sort of elite code for a long time, as powerful people put Romans on a pedestal and then claim descent from or identification with them. So many generations of Romans have staked public claims to classical heritage in one way or another that the whole city provided a backdrop for our classical mythology course. Classical texts rule over the American literary canon, not because they’re inherently superior but because appreciating them (or being seen to) conveys power. The funny part is that Ovid’s poem, apart from this final episode, is unruly, improper, chaotic, wildly imaginative — an imperialist’s nightmare.