Metamorphoses 2: Same song, different verse

Last week, I shared a Twitter thread from Emily Wilson about Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which she drew a connection between the myth of…

Last week, I shared a Twitter thread from Emily Wilson about Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in which she drew a connection between the myth of Phaethon and the climate crisis of the 21st century (the poet Eliza Griswold made this connection in a 2012 poem too). Phaethon is Apollo’s son, or so his mother says, but he doesn’t believe her — nor does he quite believe Apollo, who acknowledges him immediately. Prove it, he demands, and give me anything I ask; Apollo swears to do so and immediately regrets it when Phaethon asks to drive the chariot of the sun across the day sky. Phaethon loses control of the sun god’s chariot and sets the world on fire, drying up rivers and scorching the earth — although the sea levels drop rather than rise — in a way that reminds me of the recent fires in Australia:

The mountains

of earth catch fire, the prairies crack, the rivers

Dry up, the meadows are white-hot, the trees,

The leaves, burn to a crisp, the crops are tinder.

I grieve at minor losses. The great cities

Perish, and their great walls; and nations perish

With all their people: everything is ashes.

…The snow is gone

from Rhodope at last… (2.210–215, Humphries translation)

The heat scorches the people of Africa and darkens their skin permanently, Ovid tells us, in a lurid example of race science. The Earth (Tellus) cries out to Jove in a way that is so wrenching to read in the 21st century:

“‘I can hardly -’

the smoke was suffocating — ‘open my lips to speak;

Look at my hair, burned crisp; look at the ashes

In eyes and face! Is this what I am given

for being fruitful, dutiful? For bearing

the wounds of harrow and plowshare, year on year?

Is this my due reward for giving fodder

to flocks and herds, and corn to men, and incense

For the gods’ altars? …Save us, father;

Preserve this residue; take thought, take counsel

For the sum of things.’” (2.281–89)

Tellus doesn’t just cry out for help; she cries out for a swifter death, and wonders what she has done to deserve torture: after everything I’ve done for you, is this what I get? Don’t I matter enough in the big picture, the sum of things, to be worth saving? I read this first as a pitiable cry for help, fraught with self-blame, but on a later reading came to see it as an expression of rage and recrimination. Phaethon gets a lot of air time in the Metamorphoses and is featured in lots of later retellings of this myth, a boy who dared too much and wanted something he couldn’t have, but Ovid draws attention to Phaethon’s less celebrated victim, the Earth herself. She takes a lot of abuse in these first two books. After the first metamorphosis which created the planet out of undifferentiated chaos, the chaos threatens to take over again, in not one but two apocalyptic disasters in the space of only two books. The Metamorphoses is full of stories of undeserved, disproportionate, and cruel and unusual punishments, as Ovid often highlights.

Earth gets Zeus to strike down Phaethon with a thunderbolt to stop the conflagration, and what happens to Phaethon is terrible. But Phaethon made a choice, if a hubristic one: he wanted everyone to know who his father was, and to hold the power of a god, and to be seen doing so. In his greed for power, he almost burns the whole world down. And it strikes me that Phaethon’s own father caused Daphne’s dendrification not so long ago because of his greedy desire for Cupid (and everyone else) to know that he was the most powerful archer god, and because Cupid decided to prove him wrong to show off his own power.

When Earth cried out for Jove to just end it all quickly with a thunderbolt rather than letting her suffer, it’s not the first time there’s been a possibility that the planet is about to meet a fiery end. In Book 1, when Jove decides to wipe out the human race, he initially plans to use his thunderbolt for that too:

He was about to hurl his thunderbolts

At the whole world, but halted, fearing Heaven

Would burn from fire so vast, and pole to pole

Break out in flame and smoke, and he remembered

The fates had said that some day land and ocean,

the vault of Heaven, the whole world’s mighty fortress,

Besieged by fire, would perish. He put aside

the bolts made in Cyclopean workshops; better,

He thought, to drown the world by flooding water. (1.253–61)

It’s awfully soon to be revisiting this apocalyptic prediction again. But this isn’t the first time that Book 2 recalls images from Book 1; in fact, these repetitions are a really striking feature of these first two books.

Book 1 of the Metamorphoses had ended with the introduction of Phaethon, challenging his mother Clymene: is it really true that Apollo is his father, as she claims, or is she lying to protect her reputation? Go ask him yourself, she told him. So off Phaethon went to the palace of Phoebus Apollo in India — the sun lives in the east, waiting to rise out of the ocean, and returns under the ocean at night. Phaethon stood, astonished, looking at the magnificent palace and its magnificent doors, where Vulcan had created a masterpiece of silver sculpture. The doors show the planet Earth: the sea, the land, the sky, the sea gods, and the zodiac:

Manner there

had conquered matter, for the artist Vulcan

carved, in relief, the earth-encircling waters,

the wheel of earth, the overarching skies. (2.6–9)

Who else do we know who has conquered matter with manner and art, depicting the planet’s development from primeval chaos? Ovid himself, who began his poem with that first metamorphosis. A little hidden portrait of the artist, if you will (this sort of thing is like catnip for classicists), but also a signal that Book 2 is going to show you a metamorphosed variation on Book 1 in some other ways. As the world burns and the sea evaporates, dolphins and fish and Nereids swim deeper to avoid the air while dead seals float on the surface, a reversal of the great flood of Book 1.

Clymene, Phaethon’s mother, weeps by her son’s tomb with her daughters, for so long that they turn to trees, weeping tears of amber:

Lampetia, the fair one, tried to help her

And could not move at all, suddenly rooted

In Earth; another sister, tearing her hair,

Pulled leaves away, and another and another,

Found shins and ankles were wood, and arms were branches,

And as they looked at these, in grief and wonder,

bark closed around their loins, their breasts, their shoulders,

Their hands, but still their lips kept calling Mother!

…And then the bark closed over

The last words each one said, but still their tears

Kept flowing down, till, hardened in the sunlight,

They turned to amber, and the shining river

Receives them, bears them on, to be the jewels

Of Roman brides, hereafter. (2.344–67)

The encircling bark, the leafy hair, and the rooted feet all repeat the transformation of Daphne from Book 1. But Daphne has another counterpart in Coronis, beloved by Apollo; when he finds out from the gossiping raven that Coronis has slept with someone else, he kills her, and although he immediately regrets it, his healing gifts are useless again, just as they were useless to heal his own wound from Cupid’s arrows. (The crow, once a girl hunted by Poseidon and turned into a bird to escape him, tried to warn the raven about getting involved in divine affairs, and Apollo later turned on his messenger.) The repetitions pile up, fragmented and shuffled up but recognizable and disturbing. Why do these terrible things keep happening?

Io’s transformations took up a large part of Book 1, and she has a few bovine counterparts in Book 2. Mercury steals Apollo’s cattle and swore a human witness, Battus, to secrecy. But when Mercury comes back in a different form and Battus confesses, Mercury turns him to stone with a laugh. Then Jove turns himself into a bull, and just as Book 2 closes, he sweeps off young Europa from his “pasture” in Egypt, across the sea to Greece. The stories all get tangled up in each other and form a sort of overlapping web, running into each other over and over in a way that’s overwhelming. The repetitions are playful and artful, but because the content is so violent, the repetitions feel violent too.

I’m keeping things simple to start discussion with my students this week: pick your favorite passage, summarize it, and comment on specific words or phrases or images that you like. Or pick the passage you hate the most and explain why (I’m hoping some of them choose this option!). Because Book 2 is so overwhelming, I want to narrow the focus and bring them back for a second look in detail. I want to see what my students are making of this text so far, what seems important or salient to them, and what kind of interpretive choices they’re making on their own. I also want them to get invested in the text so that they want to talk about it.

I’ve skipped over my own least favorite myth of Book 2, the story of Callisto, a huntress, a follower of Diana. Jupiter “falls in love” with her and disguises himself as Diana to get close to her, and rapes her. Callisto, ashamed and traumatized, goes back to Diana, but nine months later, the goddess calls her to bathe with her friends, and the physical evidence of Callisto’s rape becomes clear. Diana is horrified — by the polluting presence of the slut-shamed Callisto. Juno has been watching, jealous of Callisto, and when Callisto gives birth, Juno takes her chance and turns Callisto into a bear:

Juno, with blazing mind, and the great eyes blazing,

Knew it and cried: “Of course it had to be

This way, no other, you adulterous little bitch,

To go get pregnant, to advertise the scandal

By giving birth, to have a living witness

Of Jove’s disgraceful conduct. You will never

Get away with this unpunished. I will fix you!

The form you so delight in, the lovely form

That caught my husband’s eye, I shall take from you!”

…Her human feelings were left in her bear-like form; she moaned

Held up her hands (I mean her paws (qualescumque manus)) to Heaven,

Blamed Jove’s ingratitude, and ah! no longer

Dares rest in the lonely woods, but prowls forever… (2.470–92)

Beauty is a curse, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. We meet the goddess Envy, “eating the flesh of snakes, the proper food / To nourish venom with” in Book 2 also (2.769–70), but she’s been lurking for awhile. What happens to Callisto is shockingly brutal, but the psychological torture she endures afterwards at the hands of Diana and Juno seems just as bad. They are unsympathetic, pitiless, and they have their facts completely wrong. They are the furthest thing from omniscient, or benevolent. Callisto is punished for her trauma, many times over.

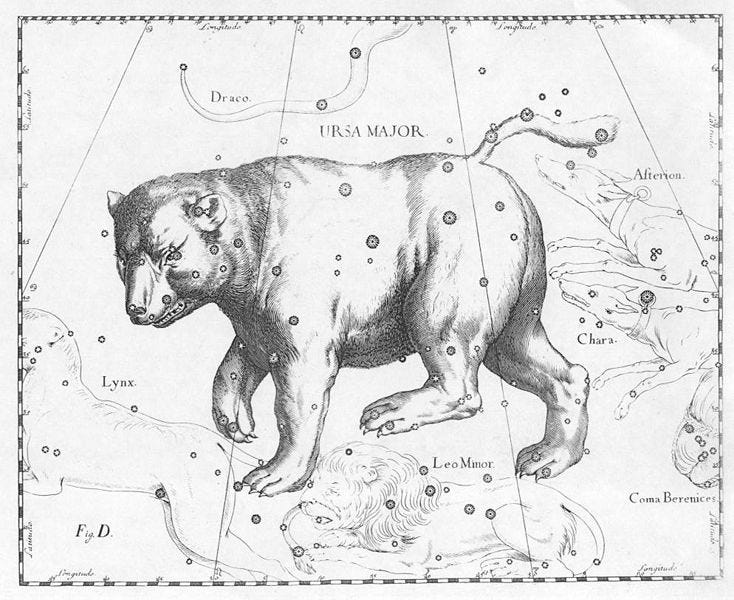

When Jupiter sees her hunted by her own son, he transforms them both into constellations. Callisto’s story turns out to be a way for us to learn the aetiological origin story of Ursa Major, but it seems to me that Ovid has put so much brutality into Callisto’s story that he has made its conclusion unsatisfying. Instead of saying “Oh, I get it now,” I’m more inclined to yell expletives at my book instead. His myths don’t help make sense of the world — they make it make less sense.

I’ll give the last word here to Nina McLaughlin, in Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung, who has Callisto ask:

There are so many other stars, all of us burning. And I see all the stars around me, and I wonder, Are you the same as me? Is this what we all are? Fires fueled by fury, burning through the nights? …I see some blazing brighter and I think: What are you remembering?

Atlas Coelestis. Johannes Hevelius 1690

Joanna Kenty is a classics professor at Temple University’s Rome campus.