Metamorphoses 4: New voices

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

In teaching the story of Hermaphroditus in Book 4 of Ovid’s Metamorphoses this week and explaining the origin of the term “hermaphrodite,” I thought a lot about what language I would use. Ovid’s stories can make readers feel less alone in any number of ways; my words as a professor can, too, or they can also make people feel stigmatized and isolated. In Ovid’s treatment, Hermaphroditus is sexualized before his metamorphosis and stigmatized afterwards, a figure of pity and fear. In fact, the Romans also stigmatized real people with intersex characteristics, as Classically Trained points out (with lots of examples from ancient literature), as signs of divine disfavor. Unfortunately, even many modern doctors are afraid of this natural phenomenon, mostly out of ignorance. Some feel a need to hide or surgically correct it, despite the medical fact that although biological sex may usually be binary, it is not always. Ovid, unwittingly or not, gives us a way to understand that through myth. I was excited to find a lot of research, much of it by undergraduate and graduate students, on non-binary gender and sexuality in the Met. available online. Hilary Ilkay wrote a great essay about reclaiming Hermaphroditus, and Sasha Barish’s beautiful Eidolon piece on gender dysphoria in the Met. discusses representation too. I needed articles like this to help me see Ovid’s poem through new eyes; my own knowledge and perspective weren’t sufficient. This is why diversity benefits the field of classics, and why new voices are always necessary to help us advance our understanding.

Reading Book 4, I found myself fascinated with the daughters of Minyas and the stories they tell. Book 3 ended with the punishment of Pentheus, who refused to acknowledge Bacchus’ divinity; the daughters of Minyas refuse also, and sit at home weaving and telling stories rather than joining the Dionysiac festivities. This can’t end well, even though sitting at home and weaving is usually the quintessentially virtuous thing for women to do in Greco-Roman stories. The Minyeides worship Minerva, a weaver herself, so they are pious as well as dutiful. Nevertheless, their patron goddess won’t protect them from their fate.

While we’re waiting for this loaded narrative gun to fire, though, the daughters of Minyas start to tell us some strange and twisted stories unlike what Ovid has been telling us so far. First, one daughter tells the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, a boy and girl who live next door to each other in Babylon and fall in love with each other as they speak through a wall, sight unseen (very “Love is Blind”).

Their parents could not keep them

From being in love; their nods and gestures showed it —

You know how fire suppressed burns all the fiercer.

There was a chink in the wall between the houses,

A flaw the careless builder had never noticed,

Nor anyone else, for many years, detected,

But the lovers found it — love is a finder, always —

Used it to talk through, and the loving whispers

Went back and forth in safety. They would stand

One on each side, listening for each other,

Happy if each could hear the other’s breathing,

And then they would scold the wall: ‘You envious barrier,

Why get in our way? Would it be too much to ask you

To open wide for an embrace, or even

Permit us room to kiss in?’ (4.61–75)

They decide to run away together, but Thisbe gets to their meeting place and runs away when she sees a lion. When Pyramus sees the lion with Thisbe’s fallen veil, he assumes that Thisbe has been killed, and kills himself. Thisbe discovers her dying lover and kills herself too, and their blood dyes the mulberry permanently red. What is odd (for the Metamorphoses) about this story — one of Shakespeare’s favorites — is that there is no divine epiphany or intervention here, just human passions and accidents.

Next, the second daughter of Minyas, Leuconoe, tells the story of Leucothoe, Apollo, and Clytie. Apollo, victim again of Cupid’s arrows, becomes obsessed with the beautiful Leucothoe, princess of Babylon, and disguises himself as her mother in order to get her alone — while the princess is weaving, notably — and rapes her. Clytie, Apollo’s lover, in a jealous rage, tells Leucothoe’s father. Even though Leucothoe tells him she was forced against her will, he cruelly buries her alive, and not even Apollo can save her, despite his efforts. Clytie, meanwhile, aggrieved that Apollo does not return to her, turns into a heliotropic flower, always turning her face toward the god who scorned her. Clytie is a nymph, but her jealousy and the wrath of Leucothoe’s father are all too human.

That was Leuconoe’s story, and the others

Listened, spell-bound, and some did not believe it,

And others said that the true gods could make

Whatever they wanted happen, but as for Bacchus,

He was no true god. (4.71–5)

Finally, the third daughter of Minyas, Alcithoe, starts to take her turn. What story should she tell? She discards several, because they’re too common (not to me, but maybe they were to Ovid’s audience); Alcithoe wants something new and exciting, something her sisters have never heard before. Considering these three sisters are only here because they refuse to worship a new god, Alcithoe’s interest in novelty seems contradictory.

Alcithoe settles on the aetiological origin story of the spring of Salmacis in Halicarnassus and its magical power to make men effeminate. Salmacis, a water nymph, “falls in love” with the beautiful young man Hermaphroditus, the son of Hermes and Aphrodite. She tries to seduce him, but Hermaphroditus is too young and inexperienced to understand what’s going on, and is frightened by her. Salmacis then withdraws to lie in wait, and pounces on Hermaphroditus like a clinging ivy vine or grasping octopus once he dives into the water. The two are fused together into a single androgynous figure, both male and female — or “half-male,” as Ovid writes. Salmacis is the poem’s first female rapist, and the result of her predation is a body of water which threatens to “soften” any male who bathes in it.

Alcithoe has succeeded in telling a surprising and unprecedented story, but the consequences of her rejection of Bacchus have arrived. As she finishes, her sisters’ loom suddenly comes to life and bursts with ivy vines and grape clusters, as the house goes dark, with spooky shrieks and drums sounding throughout the halls. Bacchus has come to exact his vengeance, and the three daughters of Minyas are turned into nocturnal bats, their storytelling powers reduced to squeaking.

Now Bacchus is worshipped everywhere, especially by his aunt and foster-mother Ino, the only one of his aunts who acknowledged him from the start. Her piety is not enough to protect her, for Juno is still angry at Ino’s sister Semele for bearing Jove’s son, and has been following the events of Books 3–4 closely.

Proud of the god she fostered, she offended

Juno, who could not stand her. ‘So,’ she thought,

‘My rival bears a child, and he has power

To transform sailors, give the flesh of a son

For his mother to tear into pieces, turn the daughters

of Minyas into bats, and what can Juno

Do beyond weeping at insults unavenged?

Is that enough? Is that my only power?

But he himself has shown me what to do:

To learn from enemies is right and proper.

He has given more than ample demonstration

In the history of Pentheus, how far madness

Can go; so why should Ino not be spurred

To madness, down the road her sisters followed?’ (4.421–34)

No punishment is ever enough for Juno; as she journeys through the Underworld to send the Furies after Ino, she only thinks that more people deserve to be down there, suffering eternal torments. Ino and her husband Athamas are driven insane, and Ino launches herself and her son into the sea, and is made a goddess. Her father Cadmus, driven to desperation by the loss of all his children and grandchildren, prays to be turned into a snake, and his wish is granted.

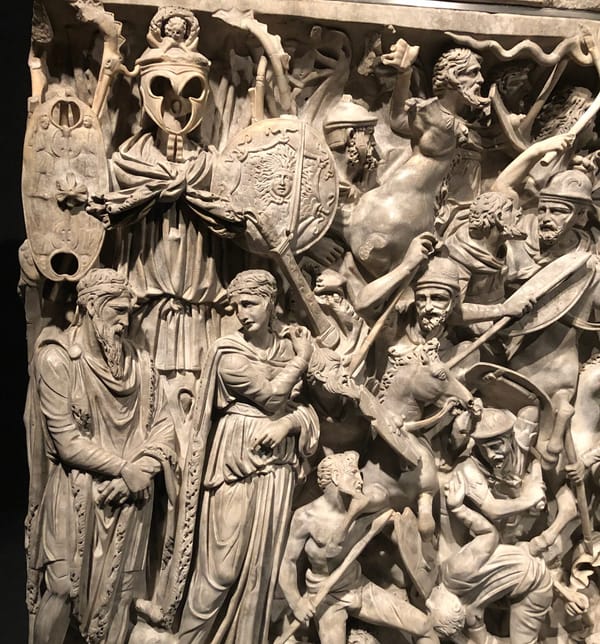

The final story of Met. 4 introduces Perseus, flying heroically in to save the damsel in distress. The damsel, Andromeda, is the princess of Ethiopia, sacrificed to a sea monster to assuage the wrath of Ammon. The book ends with Perseus casually mentioning how he came to have the head of Medusa, and how Medusa came to have snakes for hair.

And he went on to tell them of his journeys,

His perils over land and sea, the stars

He had brushed on flying pinions. And they wanted

still more, and someone asked him why Medusa,

Alone of all the sisters, was snaky-haired.

Their guest replied: ‘That, too, is a tale worth telling.

She was very lovely once, the hope of many

An envious suitor, and of all her beauties

Her hair most beautiful — at least I heard so

From one who claimed he had seen her. One day Neptune

Found her and raped her, in Minerva’s temple,

And the goddess turned away, and hid her eyes

Behind her shield, and, punishing the outrage

As it deserved, she changed her hair to serpents.’ (4.788–801)

“As it deserved”?!

Medusa sounds just like Andromeda, also “the hope of many an envious suitor” (Perseus is about to be attacked by a rival himself in Book 5). Andromeda narrowly escaped being attacked by a sea monster, while Medusa is attacked by Neptune. Medusa also sounds a lot like the Minyeides, worshippers of Minerva who might have thought their patron goddess would protect them from other gods. Now that our male poet has resumed the story, Medusa doesn’t get a speaking role. Not only do we hear from Medusa herself, we don’t even find out what happened to her and why until the action is over, and only in this casual, passing way. No new voices here.