Metamorphoses 5: Around the World

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

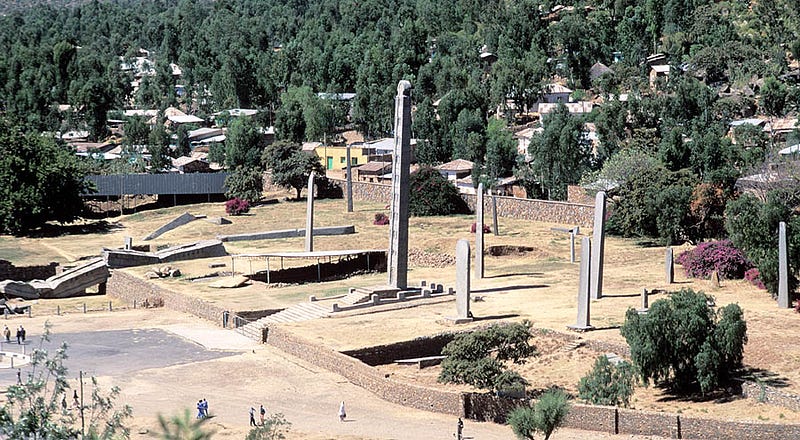

Greek mythology doesn’t all take place in Greece. To be fair, it doesn’t all take place in the real world. But the myths that are associated with real places span Europe, Asia, and Africa, from the Pillars of Hercules to the Ganges. This week, inspired by my colleague Scott Smith at UNH, my students and I put together this map, to create a visualization of mythical geography. This was our starting point for a discussion about Greece and Rome in relation to other ancient cultures, connected through art and trade as well as storytelling. As a Latin philologist, I know classical Greek and Latin, but none of the languages of the contemporary cultures and people who influenced the Greeks and Romans so much. Teaching this topic is an opportunity to learn about them myself, and every time students ask me new questions about it, I get to find out a little more.

Easternmost was Dionysus, now celebrated everywhere after the downfall of the House of Cadmus:

So all obey, young wives and graver matrons,

Forget their sewing and weaving, the daily duties,

Burn incense, call the god by all his titles,

The Loud One, the Deliverer from Sorrow,

Son of the Thunder, The Twice-Born, the Indian,

The Offspring of Two Mothers, God of the Wine-Press,

The Night-hallooed, and all the other names

Known in the towns of Greece. He is young, this god,

A boy forever, fairest in the Heaven,

Virginal, when he comes before the people

With the horns laid off his forehead. Even Ganges

In far-off India bows down before him… (4.12–20, Humphries translation)

Thanks to the fabulous community of #Classicstwitter, I had an image ready to go to illustrate real connections between India and Ovid’s Rome, an Indian ivory figurine known as the “Pompeii Lakshmi”:

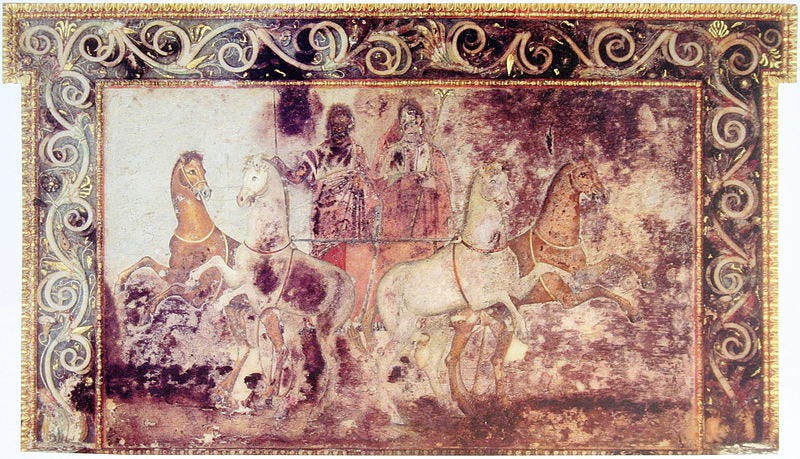

India, too, has plenty of Greco-Indian art to testify to cultural exchange, especially after Alexander the Great’s army ventured as far as the Indus river before turning back toward the Mediterranean. A delegation traveled from the Pandyan kingdom and Gujarat in India to establish diplomatic ties with Augustus, as Augustus boasts in his Res Gestae (31).

Book 4 also spends quite a bit of time in the Middle East: the daughters of Minyas tell two stories (Pyramus & Thisbe, Leucothoe & Clytie) set in Babylon, the city of Queen Semiramis and King Belus, and one (Hermaphroditus) set in Caria, near Halicarnassus (now Bodrum). The map marker in Lebanon marks the home of Europa and Cadmus, the Phoenician city of Sidon.

The map markers in Algeria and Libya track the flight of Perseus on his winged sandals, from the Garden of the Hesperides all the way to Ethiopia, where he saves the princess Andromeda from a sea monster.

Book 5 begins with a conventional epic scene: a battle between Perseus and his wife Andromeda’s former suitors in Ethiopia. The battle manages to be both horrific and monotonous at the same time; my students found Perseus to be the least interesting figure in the poem thus far, in proportion to the amount of air time he gets — even after I showed them a clip from the 1981 classic Clash of the Titans! He just runs around using Medusa’s head to turn people (and a monster) to stone, they pointed out: first the suitors, and then his rivals in Argos and Seriphos.

And Phineus, now, repents this evil warfare,

But what is there to do? He sees them all,

All images, posing, and he knows each one

By name, and calls each one by name, imploring

Each one for help: seeing is not believing,

He touches the nearest bodies, and he finds them

All marble, all. He turns his face away,

Holds out his hands, cautiously, sidewise, pleading:

‘You win, O Perseus! Take away that monster,

That face that makes men stone, whoever she is,

Medusa, or — no matter: take her away!…

I yield, and gladly, and now I ask for nothing

Except my life: let all the rest be yours!’

And all the time he spoke, he dared not look

At the the man he spoke to. Perseus made answer:

‘Dismiss your fear, great coward: I can give you

A great memorial; not by the sword

Are you to die; you shall endure for ages,

Be seen for ages, in your brother’s household,

A comfort for my wife, her promised husband,

His very image!’ And he swung the head

So Phineus had to see it… (5.208–32)

Ovid’s Perseus is a jerk. His patron goddess (and half-sister, Ovid points out), Minerva, sees him through all this and then flies back to Greece, to Mount Helicon, to see the new spring of Pegasus.

The Muses tell Minerva (their half-sister too) about some recent drama: the evil Thracian king Pyreneus tried to capture them, and then the nine daughters of Pierus started going around, telling everyone they were better singers than the Muses.

‘Swollen, it seems, also

With pride of numbers, the stupid things went swarming

All up and down Haemonia and Achaia,

Challenging us to song: ‘Quit fooling people,’

They said, ‘Quit fooling silly ignorant people

With your pretence of music! Hear our challenge!

We are as many as you are, and our voices,

Our skill at least as great. If you are beaten,

Give us Medusa’s spring, and Aganippe;

Or, if we lose, we will cede you all Emathia

From plains to snow-line; the nymphs shall be the judges.’

If it was shameful to accept their challenge,

It would have been more shameful to ignore it.’ (5.304–16)

The Pierides challenge the Muses to a singing contest, wagering the Emathian plain against Pegasus’ spring. What are the Pierides going to do with a spring more than 400 km away from their home in Macedonia? What would the Muses do with land? Why are the Pierides traveling south like an invading army to challenge the Muses? In fact, other authors tell us that the Muses themselves were often called Pierides, and were worshipped in Pieria, in Macedonia. Ovid’s story suggests that the Muses took that name and territory in conquest, just as Roman commanders took names like Africanus, Britannicus, or Asiaticus to commemorate their military victories. Maybe the Pierides and Perseus have more in common than one would think, traveling the world on heroic quests in search of a fight.

The Pierides launch right into their song, a story designed to embarrass Minerva and the Olympian gods: they sing about the war of Typhoeus and the Giants, who drove the gods into hiding in Egypt. The Muses react with the subjugation of Typhoeus, buried under Sicily and belching up fire from Mount Etna, and transition into the story of Pluto’s abduction of Proserpina from the fields of Sicily. In our class, we read the Homeric Hymn to Demeter earlier in the semester, so my students were already well-acquainted with this story. But in Ovid’s telling, Ceres acts more out of grief than rage; in the Hymn, the other gods try and fail to appease her and negotiate with her, until Zeus himself intervenes and restores Persephone to Demeter for two-thirds of the year.

In Ovid’s telling, a few metamorphoses happen over the course of Proserpina’s story. Ceres, frantically searching for her lost daughter, is helped by two water nymphs, Cyane and Arethusa, and we get to hear their stories too. (Since the nymphs are judging the Pierides’ singing contest, these stories about nymphs seem to nudge them toward siding with the goddesses.) It is Arethusa who intervenes to stop Ceres from taking out her anger on the island of Sicily, and tells her that Proserpina is in the Underworld. Several boys are transformed as a punishment: one boy is turned into a newt for laughing at Ceres, and Proserpina turns Ascalaphus into a screech-owl for tattling on her after he sees her eat the fateful pomegranate which will keep her bound to the Underworld.

The Muses are declared the victors in this singing contest, but they are not satisfied: they punish the Pierides further by turning them into magpies, “the chatterboxes of the woodland, / Still loving, as they always did, the sound / Of their own voices, the appetite for gabble” (5.676-8).

By the end of Book 5, we’re back in Greece on Mount Helicon, one of the origin points of Greek poetry according to Hesiod, after wandering all over the Eastern world as the Greeks and Romans knew it. As in Book 4, new voices threatened to take over the story and gave us a glimpse of a different kind of myth, before the powers that be — the children of Zeus — shut them up. Ovid’s mythology is disorderly and unruly, breaking loose from narrative as well as geographical constraints. There aren’t many happy endings, or even many satisfying ones; there’s no sense of fairness or rightness about these metamorphoses. I don’t think it’s just COVID cabin fever that’s making my students so impatient, even angry, with the power structure in the poem, or with who tends to come out on top from these stories.