Metamorphoses 6: Horror stories

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

In preparing to teach this mythology class, I leafed through a copy of Ted Hughes’ Tales From Ovid. I was struck as I read it by how much Ted Hughes’ version of the Metamorphoses resembled a horror movie. The growing dread in the pit of your stomach, the inability to look away, yelling “Don’t go in there!” at the book — Ovid’s myths may have ended up in children’s books, but they might be more at home in horror movies. The distinction between fantasy and horror is a matter of style, and context: Harry Potter and co. have a great time drinking Polyjuice Potion and transforming into other people until Hermione accidentally turns herself half-cat, or until a trusted teacher is revealed to be a psychotic killer.

I have always hated horror movies, and horror in movies. The first time I saw a movie in a theater, it was The Little Mermaid in 1989, and I didn’t make it past the shark. Now, it is the poor unfortunate souls in Ursula’s garden that remind me of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. They represent the metamorphosed mermaids who cut deals with Ursula in the past, and who foreshadow the fate of Ariel in the movie. I’d never thought of the metamorphosis from mermaid to human as particularly violent or grotesque until I read Daniel Ortberg’s gruesome version of the fairy tale in Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror.

I have managed to get through the spectacular Get Out and the truly disturbing Sorry to Bother You recently, and both feature metamorphoses. Both are also simultaneously comedies as well as horror movies, and the same might be said in Ovid. As in Ovid’s poem, one particularly horrifying feature of these transformations is the retention of one’s consciousness in a new body: as the world treats you differently, as prey or as a monster or whatever the case may be (no spoilers), you are painfully aware and can do nothing. Even in the surreal, fantastical world of the movie or poem, as unbelievable things happen, this psychological element of feeling a lack of control is inescapably relatable.

I had been dreading this week’s reading, the horrific story of Procne, Tereus, and Philomela, told at great length and in excruciating detail in Book 6. Arrogant, rash king Tereus of Thrace marries Procne, princess of Athens, and their marriage is cursed from the start by Furies waving the torches at their wedding. Tereus also lusts after Procne’s sister Philomela, and lures her away from her home in Athens. He imprisons her, rapes her, and cuts out her tongue to keep her from telling anyone — god or human — what he has done, but she weaves a tapestry telling her story and sends it to her sister. Procne rescues her sister, disguising herself and Philomela as mad Bacchants, and then, like the Bacchants of Book 3, turns to brutal acts of violence: she kills her son, Itys, and cooks him into a grotesque meal for his father. As Tereus leaps up to attack Procne and Philomela, all three are transformed into birds.

He looks

around, asks where the boy is, asks again,

Keeps calling, and Philomela, with hair all bloody,

Springs at him, and hurls the bloody head of Itys

Full in his father’s face. There was no time, ever,

When she would rather have had the use of her tongue,

The power to speak, to express her full rejoicing. (6.655–61)

Philomela’s voicelessness has been seen as an allegory for the censorship of Ovid himself, and for the silencing of women’s voices in many modern contexts. Donna Zuckerberg memorably wrote of the “lost library” of scholarship never written by women who could not stay in academia after they were harassed or assaulted, and began “Philomela’s tapestry” as a project to amplify women’s voices and combat this silencing effect.

The image of a cannibalistic feast is most famous from the stories of Lycaon and Tantalus, and the murder of a child to get revenge on a husband anticipates the Jason and Medea story of Book 7. But Ovid works both of these motifs, more famous elsewhere, into this extended narrative instead. We’re stuck in this story, unable to look away from the horror.

The other two major myths of Book 6 are no less horrifying, but center on gods punishing mortals for daring to think that they are better than the gods. The first is Arachne, a mortal girl in what is now Turkey who thinks that she is a better weaver than Minerva — and, remarkably, she is right. Ovid says that nymphs used to come and watch her work, entranced; I discovered the Australia Tapestry Workshop’s equally mesmerizing stop-motion weaving videos and played a clip for my students to show the effect. Minerva disguises herself as an old woman and warns Arachne not to challenge a god, but when Arachne dismisses her warnings with contempt, Minerva reveals herself, and the two begin their weaving contest.

Arachne also

Worked in the gods, and their deceitful business

With mortal girls. There was Europa, cheated

By the bull’s guise; you would think him real, the creature,

Real as the waves he breasted, and the girl

Seems to be looking back to the lands of home,

Calling her comrades, lifting her feet a little

To keep them above the lift and surge of the water.

There was Asterie, held by the eagle,

And Leda, lying under the wings of the swan,

Antiope, pregnant with twins, whose father

Was a satyr, so she thought, but it was really

Jove in disguise…

To them all Arachne

Gave their own features and a proper background. (6.102–21)

When Minerva sees Arachne’s flawless depiction of “the crimes of the gods,” she tears it apart in a rage, and then attacks Arachne so violently that Arachne hangs herself. “Moved by pity,” Minerva brings her back to life as a spider:

She sprinkled her with hell-bane, and her hair

Fell off, and nose and ears fell off, and head

Was shrunken, and the body very tiny,

Nothing but belly, with little fingers clinging

Along the sides as legs, but from the belly

She still kept spinning; the spider has not forgotten

The arts she used to practice. (6.139-45)

I imagine this is a tough passage for an arachnophobic.

Next is the story of Niobe, once a friend of Arachne before she married Amphion, the king of Thebes, and moved there. Like Arachne — and like her father Tantalus — she dared to challenge the gods, declaring herself superior with her 14 children to Latona, mother of Apollo and Artemis. Latona sends Apollo to kill Niobe’s seven sons, shooting them down as they are out riding.

A different woman,

This Niobe, from the woman who so lately

Had driven the people from Latona’s altar,

Striding the streets, with head tossed back, and haughty

And hated, even by her friends, but now

A woman even her enemies might pity.

On the cold bodies she flung herself; she gave them

The final kisses, gave them with no order,

No thought of protocol, and from them lifted

Her arms, bruised by the strain of that embracing,

And cried to Heaven: ‘O cruel Latona, feed,

Feed, batten on my sorrow! Feed the heart

Whose passion is for bloodshed, feed it full!

My seven sons are gone, and I have died

A sevenfold death. Exult, be hateful, triumph!

You are the winner. Winner, did I say?

Ha! Wretched as I am, I have more left me

Than you in all your blessedness. So many

Are dead, and still I win!’ (6.276–94)

We all know what’s coming next.

Niobe weeps so long that she turns to stone (an appropriate subject for sculpture), and is carried as a marble monument back to Maeonia, where she still weeps. The Thebans are terrorized into worshipping Latona again, and tell stories of her power and of the birth of Apollo (a story which seems a little out of place here, in Ovid’s timeline, skipped over in Book 1 to make way for the metamorphosis of Daphne).

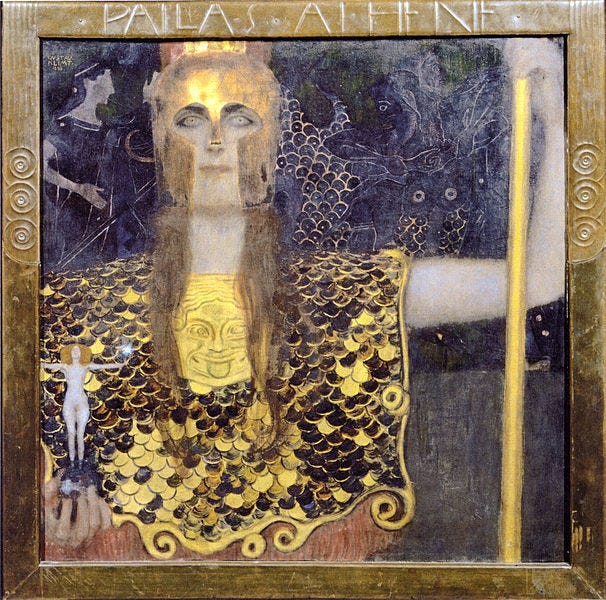

I saw a great conversation on Twitter this week about Minerva (well, Athena). Jermaine Bryant posted a meme about Greek mythology labeling Athena as “feminist,” and observed that Athena is actually an embodiment of the patriarchy in most ancient sources. Amy Pistone responded with a thoughtful thread on Athena as “cool girl,” a source of false female empowerment. While Athena is a literal warrior goddess, she takes the side of male heroes and the will of Zeus, often at the expense of women. Her worshippers, like Medusa and the daughters of Minyas in the Metamorphoses, get no protection from their patroness. Her detractor Arachne is driven to suicide. What would it matter to Athena if a mortal woman is a better weaver? Would she no longer be the goddess of weaving?

On the mortal side, Procne and Philomela exact their vengeance with the murder of a child, repaying monstrosity with monstrosity. Minerva, Latona, Procne, and Philomela all represent female vengeance, but not justice. The “strong female character” supposedly sought after in today’s movies, shows, and video games isn’t just a question of power or agency, but of outlook: she has a life of her own, a mind of her own, and doesn’t empower herself at the expense of other women. These women of Book 6 might be sympathetic, but I don’t think they’re feminist.