Metamorphoses 7: Plague

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

In any other semester, Medea’s adventures flying around the Mediterranean in a chariot drawn by dragons would be the star of Book 7 (and I’ll get to that). But this semester, spring 2020, we all took special notice of another episode. Book 7 ends in Aegina, off the coast of Athens, where King Aeacus tells Cephalus about a recent plague. You could read this poem 50 times and find something new every time, I suspect, not only because it’s so long and complex but because we change as readers and focus on different things. It’s why scholars can still find new things to say about 2,000-year-old poems, and why every new translator offers new understanding as well as new words.

It was Juno who caused the plague, Aeacus says, but we didn’t know it: she was jealous of Aigina, a nymph Jove had sex with, and punished the island for it. “We thought the cause / was mortal, and we fought with every resource / of medicine against it, but the evil / had too much strength for us.” The animals die first, but then the contagion spreads to humans.

Contagion thickens, and the plague, grown stronger,

Fastens on men, on the walls of the great city.

Men’s vitals seem to burn: the proof is given

By a red flush and a difficult breath; the tongue

Thickens, and the lips are cracked and dry; the sick

Cannot lie still in bed, they cannot bear

The weight of covers over them; they try

To get some coolness from the ground, which burns,

Itself, from the heat of their fever. Even our doctors

fare as the others do, or worse; the nearer

One comes to the sick, the greater his devotion

In looking after others, the more quickly

He comes to his share of death. …

In delirium

Many poor souls leap from their beds, and stagger

Too weak to stand, and others, too weak for leaping,

Roll out on the ground. They flee their household gods,

Since no man’s home is sacred. Each man’s home

Seems to him Death’s abode. Since no man knows

the cause, he blames his little habitation.” (7.550–76)

King Aeacus’ people never recover. Instead, Jove takes pity on him and turns a colony of ants into new citizens, the “Myrmidons” (“ant-men”). The descendants of these Myrmidons will follow Achilles, Aeacus’ grandson, to Troy. There, they’ll experience yet another plague, described in Iliad 1 and at greater length in Pat Barker’s recent Silence of the Girls, told from the perspective of Briseis, a captive woman living with the Myrmidons.

The plague in Aegina is certainly not COVID-19. But the feeling of panic over the unknown is all too familiar, feeling that Death could be lurking anywhere. Even in the modern era, armed with microscopes and germ theory and mechanical ventilators, we can still feel the same helpless dread, wondering if the virus is all around us. We may be better equipped than an ancient city to reduce our chances of getting the virus — and some of us are better equipped than others — but anyone could get it. Worst of all is Ovid’s note about doctors falling ill as they care for patients, which has proven to be one of the most upsetting aspects of the 2020 pandemic. As lots of think pieces have pointed out lately, epidemics like the Athenian or Antonine plague transformed ancient societies. We don’t know what kind of metamorphosis this plague will cause in our world.

Amid all these haunting parallels, the story of Medea was a bit of an escape, a fantastical adventure. Book 6 begins as the story of Jason and the Argonauts, but Jason and the Argonauts are just a backdrop for Medea. She was the star of Euripides’ tragedy, the star of a Roman tragedy by Ennius, and the heroine of Book 3 of the epic Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes — and those are just the versions of her story that survive. In Euripides’ play, Medea has traveled with Jason to Corinth. He has decided to marry the princess of Corinth and raise his children with Medea in the palace, forsaking Medea to improve his own prospects. Medea is crushed, and has a long conversation with herself about what to do before deciding on a gruesome revenge: she will kill her children to punish Jason, and kill his bride-to-be with a poisoned cloak. Ovid introduces Medea to us as a young girl, in love for the first time, a Colchian princess in love with a Greek hero, having a conversation with herself at an earlier point which foreshadows all this tragedy to come:

What has he done? Only the cruel-hearted

Would not be moved by Jason’s youth, his manhood,

His noble birth. And even if these were lacking,

His beauty would move a heart of stone — at least

It has moved mine. And if I do not help him,

The bulls will blow their fiery breath upon him,

The enemy he has sown in earth attack him,

The greedy dragon snatch and seize upon him.

And this, if I allow it, will prove me daughter

Of tigress, stony-hearted, iron-hearted!

Why can not I look on as he is dying,

Disgrace my eyes by looking on? Why can not

I urge the bulls against him, and the warriors

Sprung from the earth, and the unsleeping dragon?

God grant me better grace! But this is not

A question of praying, but doing. Shall I then

Betray my father’s kingdom, rescue a stranger,

Who, saved, sails off without me, marries another,

Leaves me to punishment? If he can do it,

Then let him die, the ingrate! No! He could not,

He does not look as if he could, his spirit

Is noble, his body handsome. I need never

Fear he would cheat me, or forget my service. (7.26–44)

According to Ovid, Medea’s inner dialogue habit starts early. It’s no big deal not to want an innocent man to die, she reassures herself, trying to keep a grip on objectivity and rationality, but she can’t help herself. We readers know how this ends, and the irony of her faith in Jason is overwhelming.

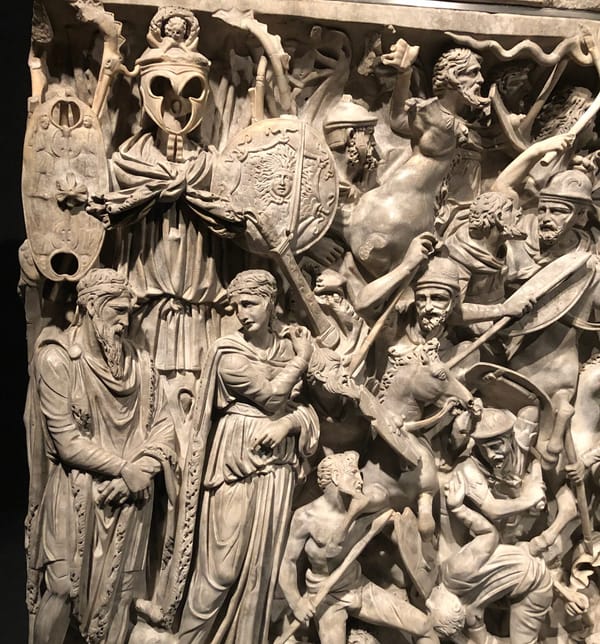

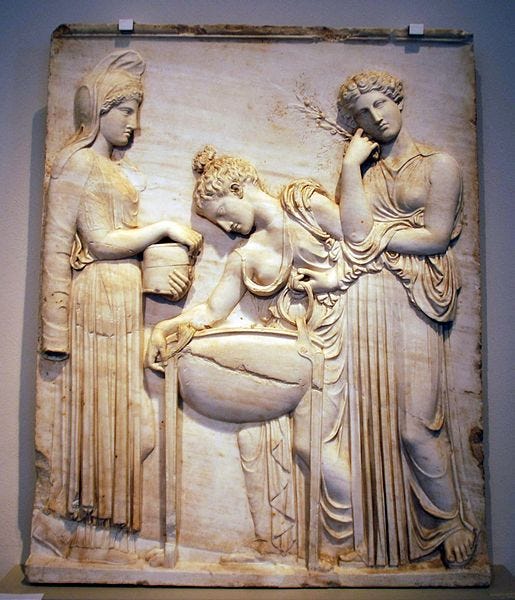

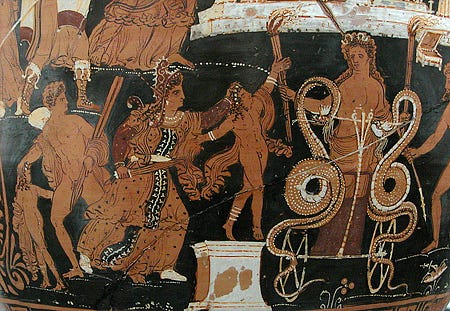

She meets Jason in the grove of the Underworld goddess Hecate, and when he proposes marriage to her (in exchange for her help), she gives in immediately and gives him magic herbs. Ovid hasn’t really told us what Jason needs the herbs for in any detail, or what he’s even doing in Colchis; all that has to be filled in by other, earlier poems. His wicked uncle King Pelias sent him after the golden fleece of King Aeëtes, but to get it, he has to yoke fire-breathing bulls, plow a field, kill the warriors who spring out of the earth, and then contend with the dragon who guards the fleece. Medea’s herbs protect him from the bulls’ fiery breath. She casts a spell over the warriors, and gives Jason a charm to lull the dragon to sleep.

On a trip through the Vatican Museums, I found a vase which showed a slightly different, hilarious version of Jason’s heroic quest with a bit of a hiccup. I can just hear Minerva: “Didn’t I tell you to wait until the dragon was asleep?!”

Jason’s heroic quest is complete (no thanks to Jason, really), but Medea is just getting started. She returns home with Jason — Ovid skips the part where she kills her brother and scatters his body parts to buy herself time to get away from her father — and meets his father, Aeson. Jason asks if she can give some of his youth to his father; absolutely not, Medea answers, but maybe she can do something better.

…And she raised

Her arms to the stars, three times, and turning thrice,

Thrice sprinkled her head with quick-caught running water,

Thrice cried a wailing call, and knelt, and prayed:

‘O Night, most true to mysteries, O stars

Whose gold with the moon’s silver shines and follows

The fires of day, O Hecate, triple goddess,

Witness and helper of magic art and charm,

O Earth, provider of the herbs of magic,

O winds, O little breezes, O streams, O mountains,

O lakes, O groves, O gods of the groves, O gods

Of night, come, help me, help me, help me!

You have before this, when I wanted, seen me

Make streams return to their sources, while their banks

Wondered; you have seen me still the angry oceans,

Rouse the calm waters, drive the clouds away

Or marshal them together, exile winds,

Recall them; you have seen me break the fangs

Of serpents with my charms and incantations,

Root up the rocks from the soil, root up the oak-trees,

Move forests, shake the mountains, make earth rumble,

Call ghosts from graveyards.’ (7.185–206)

Then the witchy cauldron-stirring starts in earnest: Medea brews up a potion which she pours into the veins of Aeson after cutting his throat, and he springs up young and handsome again. Even the gods take note, and Bacchus asks Medea to rejuvenate all his beloved nurses too. But when wicked King Pelias’ daughters tell her to do the same for their father, she leads them through the throat-cutting part but adds no herbs to her cauldron, and lets them boil their father’s body instead before climbing into her dragon-born chariot and dashing off.

As she flies, Medea passes over places which Ovid casually mentions as locations of metamorphoses, without any details or context, which I now think of as “flyover myths.” In the space of a mere three lines, she lands, finds Jason with his Corinthian princess, kills her children, and is off again; Ovid is not rehashing the old versions of her story. She takes refuge in Athens with King Aegeus and gets to marry a Greek king after all. But she almost poisons a young hero before Aegeus realizes that it’s his long-lost son, Theseus. Medea, now transformed into a wicked stepmother of sorts as well as a witch, takes off again, leaving the story entirely.

Book 7 ends with more human drama, the long tale of woe of King Cephalus of Athens. He tells Aeacus’ son that he was abducted by Aurora, goddess of the dawn, and kept from his devoted wife Procris. When he returned, he decided to disguise himself and test Procris’ fidelity.

‘What use is there in telling you how often

Her chastity rejected my temptations?

“I keep myself for one,” she would always tell me,

“Wherever he is, I save my pleasure for him.”

What more could any sensible man have wanted?

I was not satisfied, I kept on fighting

To wound myself. I promised her a fortune

For just one night, and as I doubled the promise

I made her hesitate, and then, victorious,

Wickedly so, exclaimed: “Ha, evil woman!

I was no real seducer, but your husband,

Both witness and detective!” She said nothing,

Never a world, but a shamed and beaten woman

Fled from her treacherous husband and his house,

And hating him and all the race of men

Went wandering the mountains, all devoted

To the worship of Diana, virgin huntress.

I was lonely, and my passion burned the fiercer

In loneliness; I pleaded for her pardon,

Confessed that I had sinned and might have yielded,

As she had, if such gifts were offered to me.

There was, it seems, some satisfaction for her

In my confession; she came back to me.

And so we spent delightful years together.’ (7.730–52)

Unfortunately, Cephalus continues, Procris becomes suspicious of her husband’s fidelity too and decides to test him herself. She follows him into the woods where she thinks he’s having an affair with “Aura” (breeze), not realizing that he was just poetically thanking the breeze for relief on a hot day. Cephalus mistakes her for an animal and kills her with his own javelin, a magic weapon that never misses when it is thrown.

Nobody turns into an animal at the end of this story (although one animal, a hound given to Procris by Diana, turns to marble). Medea doesn’t undergo a metamorphosis into anything either, at least on the outside. But in both stories, relationships change from love into jealousy, and people make themselves and each other miserable. A love story turns into a tragedy. Ovid’s stories are getting longer and more realistic as the Metamorphoses unfolds. There are still plenty of elements of magic and fantasy in this part of the poem, but more human psychodrama besides, as the gods fade into the background. Ovid is also flexing his poetic muscles in transforming old poems and plays into a new epic. He looks for gaps in earlier versions and zooms in to expand and elaborate, so that even a character like Medea gets to show a new face to his readers.