Metamorphoses 8: Mutual Aid

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

This week, something we all really needed: a (mostly) pleasant story with a happy ending in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. A story about hospitality and sharing food, which feels all the more important today, as my neighbors very kindly pick up groceries for me and bring them to my doorstep. The Ovidian story I’m thinking of is the tale, almost a parable, of Baucis and Philemon, an elderly couple of no particular fame, with no wealth to speak of. But when a stranger and his son come knocking at their door, Baucis and Philemon lay out all the food they have (a task which slaves would do in a richer household, but everyone’s both slave and master here, Ovid says), in the name of hospitality. They do this out of piety and care for their fellow humans, but what they don’t know is that their guests are not human at all, but the gods Jove and Mercury in disguise. Jove and Mercury have tried every house in the village, and no one else would take them in.

All around the table

Shone kindly faces, nothing mean or poor

Or skimpy in good will. The mixing bowl,

As often as it was drained, kept filling up

All by itself, and the wine was never lower.

And this was strange, and scared them when they saw it.

They raised their hands, and prayed, a little shaky —

‘Forgive us, please, our lack of preparation,

Our meager fare!’ They had one goose, a guardian,

Watchdog, he might be called, of their estate,

And now decided they had better kill him

To make their offering better. But the goose

Was swift of wing, too swift for slow old people

to catch, and they were weary from the effort,

And could not catch the bird, who fled for refuge,

Or so it seemed, to the presence of the strangers.

‘Don’t kill him,’ said the gods, and then continued:

‘We are gods, you know; this wicked neighborhood

Will pay as it deserves to; do not worry,

You will not be hurt, but leave the house, come with us…’ (8.678–91)

Jove and Mercury punish Baucis and Philemon’s impious neighbors with a flood, transforming the village into a marsh, and promise the surviving couple anything they want. They talk it over, and the only thing they want is eventually to die on the same day. The gods grant their wish and turn their house into a grand temple, where the happy couple live as priests until their death day, when they turn into a pair of trees standing together.

This myth, very similar to the story of Lot and his wife in Sodom and Gomorrah in the Old Testament, shows how hospitality was especially valued in ancient Greece. Enemy warriors on the battlefield in the Iliad realize that one of their grandfathers was generously hosted by the other’s grandfather, and because of this guest-friendship in their family tree, they decide not to fight each other. In the Odyssey, kings and princes go traveling around the Mediterranean to unknown places and count on generous hospitality, xenia, to survive. You wash up on a beach somewhere with nothing, and (at least if you’re as lucky and clever as Odysseus) you’re soon being treated in princely fashion. Food and clothes and a bath are given before the host learns if their guest is the sort of rich and powerful noble who will be able to repay the favor someday. This kind of generosity with no questions asked is expensive, maybe even dangerous, and requires you to go out of your way and make yourself vulnerable for a person with whom you have no relationship at all. But that’s exactly why it’s such a big deal, an act of worship of Zeus Xenios, Zeus of Hospitality. Hospitality with strings attached or with means testing, a check to see how much is too much, isn’t real hospitality. Hospitality isn’t really practical, at least in an immediate way. It’s just faith in the principle that everyone deserves to be able to get a good meal when they need it. Someday you could be the one who needs it.

Faith is a key part of this story in Ovid’s poem, because the story of Baucis and Philemon is told by an old Athenian soldier, Lelex, after his young comrade Pirithous describes a myth about the exploits of Hercules as a “fairy tale”: “The gods have no such powers, Achelous; / To give and take away the shapes of things” (8.615–17). This is sort of hilarious at the halfway point of a mythological epic about Metamorphoses. Lelex’ story is apt, hinging on hospitality without the knowledge that one is an unwitting participant in a test of the gods, with the gods in the house, sitting at the kitchen table. You can never be too careful.

Achelous himself picks up the storytelling baton with another myth about faith and food, this one more of a horror story. It’s even got a horrible monster, like the fury Tisiphone or the goddess Envy earlier in the poem. King Erysichthon cut down an oak sacred to Ceres, even when he heard the tree nymph crying out and warning him, and saw the oak bleed as he cut. Ceres curses him, sending Famine to hunt him down and haunt him.

The oread, soaring high, came down

To Caucasus’ bleak mountain-top, unyoking

The dragons from the car. She looked for Famine

And found her, in a stony field, her nails

Digging the scanty grass, and her teeth gnawing

The tundra moss. Her hair hung down all matted,

Her face was ghastly pale, her eyes were hollow,

Lips without color, the throat rough and scaly,

The skin so tight the entrails could be seen,

The hip-bones bulging at the loins, the belly

Concave, only a place for a belly, really,

And the breasts seemed to dangle, held up, barely,

By a spine like a stick-figure’s; and her thinness

Made all her joints seem large; the knees were swollen

Balloons, almost, the ankles lumpy tubers. …

Famine, whose task is always opposite

To that of Ceres, none the less obeyed her,

Flew through the air on the wind’s wings and came

To Erysichthon’s palace…

She twined her skinny arms around him, filled him

with what she was, breathed into his lips, his throat,

And planted hunger in his hollow veins. (8. 799–821)

Erysichthon eats and eats and eats, and is still hungry. “The more he wolves, the more he wants,” is how Humphries (loosely) translates it. When he runs out of food, he sells his daughter into slavery to buy more, over and over, until the only thing he has left to eat is his own body.

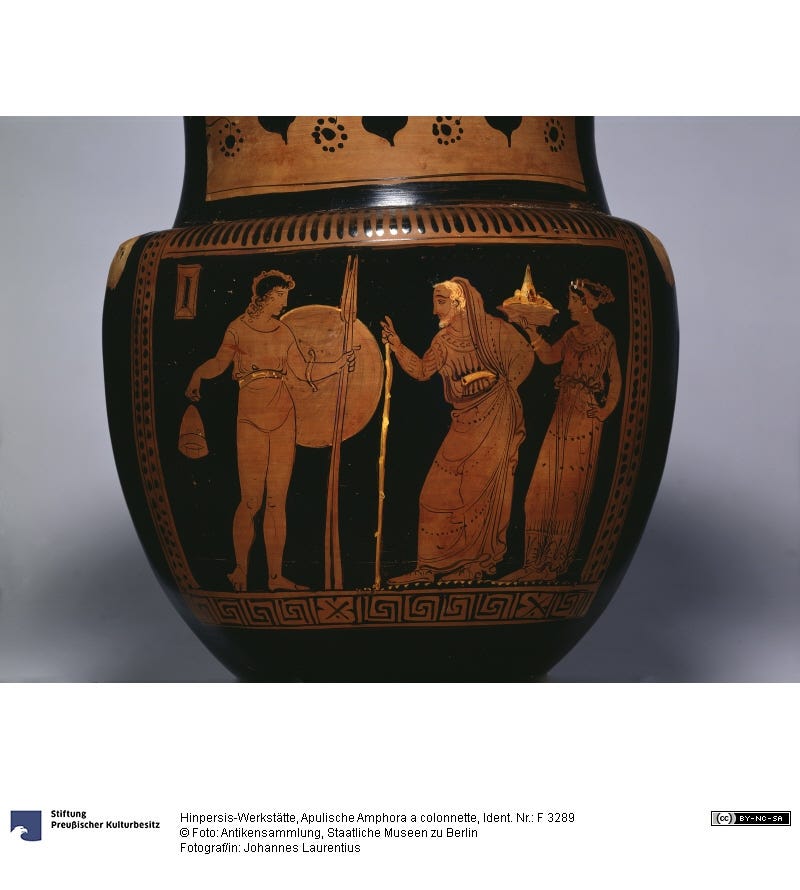

The occasion for Theseus and Pirithous’ visit to Achelous, the backdrop for these two stories, is the end of the Calydonian boar hunt. This myth is to Greek mythology what the Avengers movies are to comic books: the Calydonian boar hunt involves the greatest heroes of a generation, the Argonauts and the fathers of the heroes at Troy, all joining forces to appear in a sort of all-star hunting team. The target is a vicious boar the size of an ox, sent by Diana to terrorize the countryside after she was left out of a sacrifice by accident. This all-star team even includes a female warrior, the swift-footed Atalanta, who draws first blood from the boar. Meleager kills the boar but gives the hide as a trophy to Atalanta, partially hoping she’ll fall in love with him.

Not only does Atalanta not fall in love with Meleager, his teammates are so angry with him that they start fighting, and Meleager kills several of them, including his two uncles. His mother Althaea, when she finds out that her son has killed her brothers, decides after much agonizing to avenge her brothers. When she gave birth to Meleager, the Fates told her then when one log in the fire burned, he would die; she saved the firebrand and protected it, but now throws it into the fire and kills her son.

In making this decision, Althaea gives a speech to herself, like Procne or Medea in earlier books, deliberating what to do. In fact, earlier in the same book, we’ve already had a similar speech from Scylla — not the sea monster of the Odyssey, but the daughter of King Nisus of Megara. Megara is under attack by King Minos of Crete, and Scylla has fallen in love with her city’s attacker from afar, watching him from the walls. She even knows the story of his birth, as we do: he is the son of Jupiter and Europa. She decides to betray her city and help Minos to capture it, but Minos is appalled by her lack of patriotism. Scylla cries out at him, in a speech worthy of Medea (actually, literally borrowing from other texts about Medea):

‘Do you leave me, then, who gave you

Success and victory, leave me, who put you

Above my fatherland, above my father?

Do you leave me, cruel king, in victory,

Thinking my guilt no service? Was the gift

Nothing at all? Were all the love and hope

Centered upon you nothing? Where am I

To go to now, deserted? Back to my country?

It is beaten, it lies low. But even suppose

It still remained, my treason has closed it to me.

Go back to my father? But I have betrayed him.

My people hate me, as they should; my neighbors

Fear my example. I have made myself an exile

from all the world for Crete alone to take me.

If you forbid me Crete, and leave me here

I will know Europa never was your mother,

But quicksands must have been, or evil whirlpools,

Or some Armenian tigress! You are no son

Of Jove, your mother never was deluded

by a bull’s guise; that story of your birth

Was all a lie. Truth is, you were begotten

By a real bull, a fierce unnatural creature

That could not find a heifer to his liking!’ (8.108–119)

Scylla says all this — contradicting Ovid’s own poem in her anger — knowing that Minos’ wife Pasiphae has actually had sex with a bull and borne the monstrous half-bull Minotaur, so her accusation is less far-fetched and a lot more personal than it may sound. Her speech recalls another famous abandoned woman of Greek mythology, a woman who saved her lover’s life and was then marooned for her trouble: Ariadne, Minos’ daughter, who helped Theseus defeat the Minotaur.

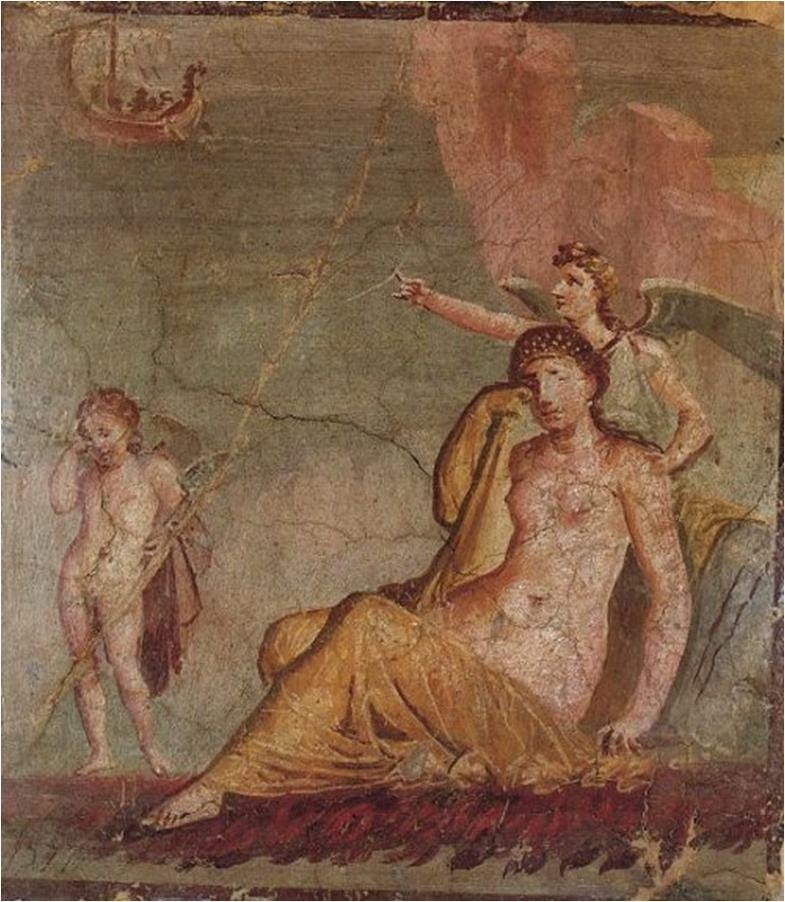

We get from Scylla to Crete to Achelous by following the famous flight of Daedalus, the master craftsman (and one of my favorite characters in Madeline Miller’s Circe) who built the labyrinth in Crete as a prison for the Minotaur. Fed up with his employers, Daedalus decides to make a break for it with his son, Icarus, and builds a pair of wings for each of them out of wax and feathers.

And Icarus, his son, stood by and watched him,

Not knowing that he was dealing with his downfall,

Stood by and watched, and raised his shiny face

To let a feather, light as down, fall on it,

Or stuck his thumb into the yellow wax,

Fooling around, the way a boy will, always,

Whenever a father tries to get some work done.

Still, it was done at last, and the father hovered,

Poised, in the moving air, and taught his son:

‘I warn you, Icarus, fly a middle course:

Don’t go too low, or water will weigh the wings down;

Don’t go to high, or the sun’s fire will burn them.

Keep to the middle way.’ …

Between the work and the warning the father found

His cheeks were wet with tears, and his hands trembled.

He kissed his son (Good-bye, if he had known it),

Rose on his wings, flew on ahead, as fearful

As any bird launching the little nestlings

Out of high nest into thin air. (8.195–215)

Icarus, of course, flies too close to the sun, feeling like a god in flight, and falls to his death as his wings melt. It’s yet another cautionary tale about hubris — Icarus ignores his father’s flying advice just as Phaethon ignored his father’s advice in Book 1 — but Daedalus is clearly offering the moral of the story when he tells Icarus to “follow the middle way,” choose moderation and the “golden mean.” Baucis and Philemon were happy with moderation too — even poverty. Romans craved glory and exceptionalism, but they also told stories valorizing its opposite: the dictator Cincinnatus who gave up all his power to go home to his farm, the triumphant general Manius Curius who was happy eating turnips for dinner. Fancy food doesn’t satisfy hunger any better, as Erysichthon attests, and greed is never really satisfied. It’s no wonder that Icarus shows up all over literature and pop culture: that lesson never gets old.