Metamorphoses: Book 1

This semester, I’m teaching in Rome — classical mythology, Latin, and ancient Greek. In case you’re not jealous already, I’ve decided to…

This semester, I’m teaching in Rome — classical mythology, Latin, and ancient Greek. In case you’re not jealous already, I’ve decided to read Ovid’s Metamorphoses in its entirety with my mythology class. It’s been awhile since I spent quality time with this text, so I’m excited about it, and I thought I’d share my thoughts and some of our class discussions about it.

I chose to teach this text for a few reasons. First, I wanted to read literary texts in this course (as I do in most others) to get a real sense of an ancient voice and an artistic treatment. Second, I wanted to assign as few books as possible, because the students are studying abroad where it’s hard to get books, and probably spending all their money on pizza. Third, my mythology course is cross-listed in Classics and English, and Ovid’s Met. was monumentally influential for English literature.

In shooting have I stedfast hand, but surer hand had hee

That made this wound within my heart that heretofore was free.

Of Phisicke and of surgerie I found the Artes for neede,

The powre of everie herbe and plant doth of my gift proceede.

Nowe wo is me that nere an herbe can heale the hurt of love

And that the Artes that others helpe their Lord doth helpelesse prove.

Apollo to Daphne; Arthur Golding, 1567 — a.k.a. Shakespeare’s Ovid

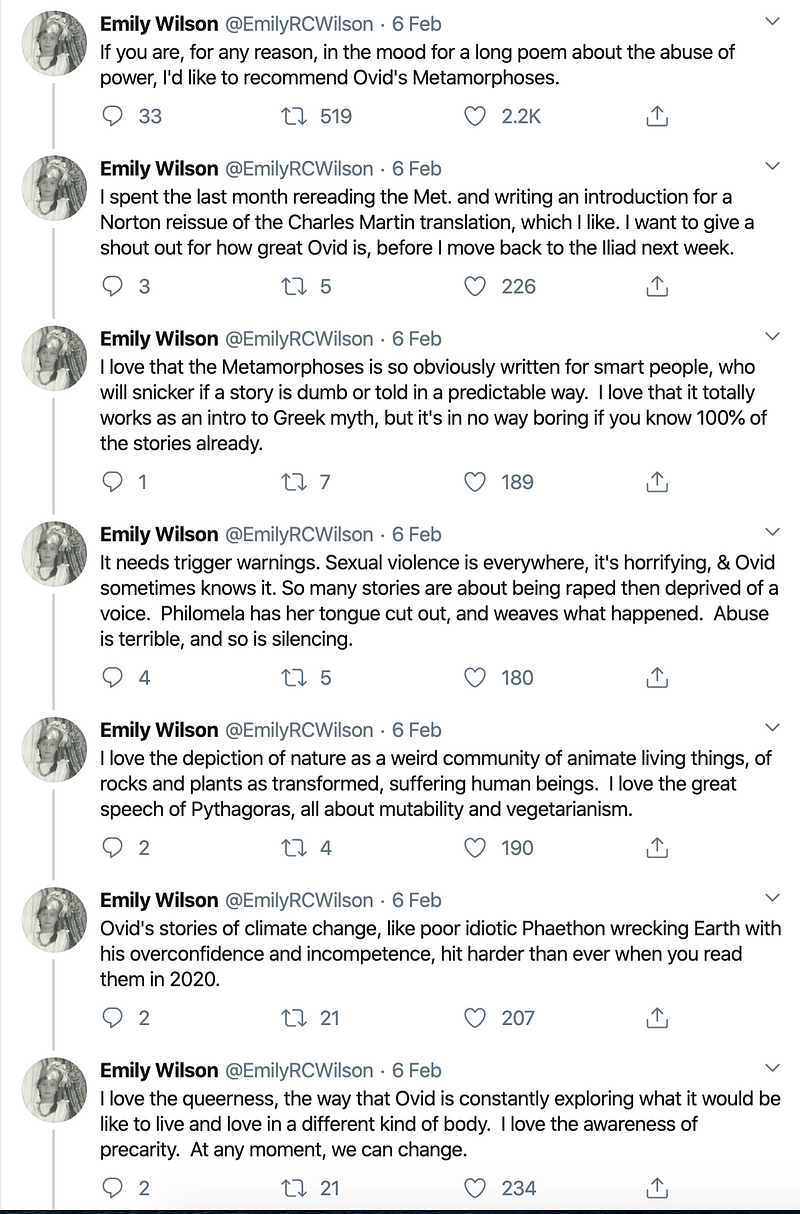

And just in time, a thread from Emily Wilson recommending the poem, if you needed more encouragement!

I did have some reservations about it, for a reason Emily highlights. The Metamorphoses has an awful lot of stories of rape. When translators or commentators try to dress it up as romance, that really just makes it worse. Columbia students organized a protest in 2015 to demand trigger warnings for rape and sexual violence in the Met. in their Great Books course. Many classicists and writers (Madeline Kahn, Kelly McArdle, Daniel Libatique, Carole Newlands, Stephanie McCarter & Jia Tolentino, and Katy Waldman, to name only a few) have written recently about how to engage with the pervasiveness of sexual violence in Ovid’s text.

As a teacher, how am I going to handle this? Should I wait for students to bring it up? Will I be ruining Ovid for them if I bring it up? There will be students who will be really uncomfortable if I do, who might not want to speak up in class anymore. On the other hand, if I don’t bring it up, students may think that I don’t think sexual violence is a big deal, or that I don’t think it’s traumatic — and statistically speaking, my class may well include someone who has been assaulted, and I could make their trauma worse through negligence. Also, it’s not like the sexual violence is hidden or implicit, the result of polemical reading between the lines. It’s right there on the page. I can either teach students to notice it and think about it, or teach them to ignore it and look past it.

I brought it up.

We started this week with Book 1, in which Ovid tells the stories of the creation of the universe (a metamorphosis from chaos into order), races of humanity declining in morality until Jove creates a great flood (very Biblical) to purge the earth of wicked humans (including the savage Lycaon, whom he turns into an equally savage wolf). In the flood, Ovid has some fun describing sea cows and Nereids swimming down city streets and through temples — it reminded me of of this Photoshopped image which circulated after Hurricane Harvey:

Two good humans, Deucalion and Pyrrha, survive by taking shelter on Mount Parnassus to become the ancestors of a new, restored humanity. Apollo founds his temple at Delphi. Then things take a turn from cosmic to erotic. Apollo brags about his archery to Cupid, who proves himself superior by shooting Apollo with a love arrow — and shooting the object of his affections, the nymph Daphne, with a lead arrow to make sex repugnant to her altogether. Apollo chases her, and in her terror she prays to be saved and is transformed into a laurel tree, which Apollo promptly claims for himself and his rites.

Daphne’s father, the river Peneus, withdraws in grief:

Here dwells

The mighty god himself, his holy of holies

Is under a hanging rock; it is here he gives

Laws to the nymphs, laws to the very water.

And here came first the streams of his own country

Not knowing what to offer, consolation

Or something like rejoicing…

(nescia, gratentur consolenturne parentem)

(Humphries translation, 1.572-578)

River gods come to speak to Peneus, but should they congratulate him for the honor bestowed on his daughter by Apollo, or express their condolences for the daughter he has lost? (He used to complain to Daphne about not having any grandchildren, and he certainly won’t now, so maybe they would console him for that.)

There is doubt here, in the poem itself, over what the Apollo and Daphne story means, how to interpret it. Is this a good outcome? Is this a happy ending to a marriage plot, a nice bedtime story for children, or a brutal illustration of divine cruelty? Daphne is actually made to consent to the final settlement, nodding her branches as if in agreement, but that doesn’t exactly undo the terror of her exhausting flight from Apollo.

On the Apollo and Daphne episode, Jay Reed notes: “this episode is the first of a long series of myths in the poem that showcase possibly or most definitely nonconsensual activity… This component of the poem can perturb and unsettle readers, particularly when the Metamorphoses is read with a narrow view to its aesthetics and wit. As so often in the poem, the tone seems too suave and humorous …for the violent content. The historicist answer that Ovid, being a man in a resolutely male-centered and regrettably unenlightened place and time, intended these narratives simply to amuse fails to satisfy.” It’s not that Ovid wrote a poem that hasn’t aged well, but that he wrote a poem that causes more confusion and discomfort than it resolves.

Meanwhile, the one river god missing from the gathering of river gods around Peneus is Inachus, who is mourning the loss of his own daughter, Io. Jove “fell in love” with her, but when his wife Juno shows up, he turns Io into a cow to cover up his infidelity (even though Juno knows full well what’s going on, and punishes Io for it). Poor Io finds her way to her father eventually and scratches out her name in the dust with her little hoof, and her father weeps — for the bovine grandchildren he’s going to have:

“‘Not even death can end my heavy sorrow.

It hurts to be a god; the door of death,

Shut in my face, prolongs my grief forever.”’

And both of them were weeping, but their guardian,

Argus the star-eyed, drove her from her father…” (1.662-666)

Mercury comes along at Jove’s command to free Io from her torment. He tells her guard, the hundred-eyed Argus, the tale of Syrinx to make him fall asleep (Syrinx was a nymph, transformed to reeds to escape the lust of Pan). Mercury kills Argus, and Juno, still angry with Io, preserves her servant Argus’ eyes by placing them on the peacock’s tail. Io eventually becomes human again, bearing a son who befriends Phaethon, the offspring of Apollo and a nymph, Clymene.

These stories are all folded into one another, repetitive and horrifying in different degrees. The physical descriptions of transformations, of hair becoming branches, of reeds whispering, of Io’s mooing, are poetic and clever, described vividly and lovingly (?). It’s tragic, in the sense of being beautifully sad. Is it OK to think this is beautiful and to luxuriate in the language?

I hope that my students enjoy it enough to find that this is a problem.

We get to go to the Galleria Borghese in a few weeks to see Bernini’s famous statues of Apollo and Daphne (pictured above) and of Hades and Persephone. One of the things I’d like them to think about is who Bernini imagined as the audience for these statues, and what he wanted them to feel when they saw them. Are they “beautiful,” and to whom? We’ll also be thinking about the use of Greek myths as prestige objects in the home of a prominent papal family, the Borghese.