Graphic content: using mind mapping in class

In my mind, there are three great ways to use mind maps in the classroom: 1) mastering a lot of new information in an intro class; 2) going beyond rote learning; or 3) planning an essay, paper, project, or complex assignment, especially in a group

When we come across new information, the first thing our brains try to do is relate that new piece of information to something we already know. Our brains try to find an existing filing cabinet where the new piece of information will fit, not start a whole new filing cabinet. The more prior knowledge we have in that filing cabinet in our memory already, the more quickly we can process new, related information and file it away. In other words, the best learning depends on the connections learners make between pieces of information.

While I was reading about active learning and pedagogical approaches for better lecturing, I kept encountering suggestions about diagrams, "graphic organizers" and mind maps. I read that mind maps can be a great way to make sure students are not just learning (or trying to learn) a bunch of unrelated facts, but genuinely understanding concepts and the way facts relate to one another.

A Venn diagram or a timeline is an example of a graphic organizer: it's a visual representation of how things are related. Expressing ideas in a new way is a useful exercise for any learner, but can be particularly helpful for neurodivergent learners.

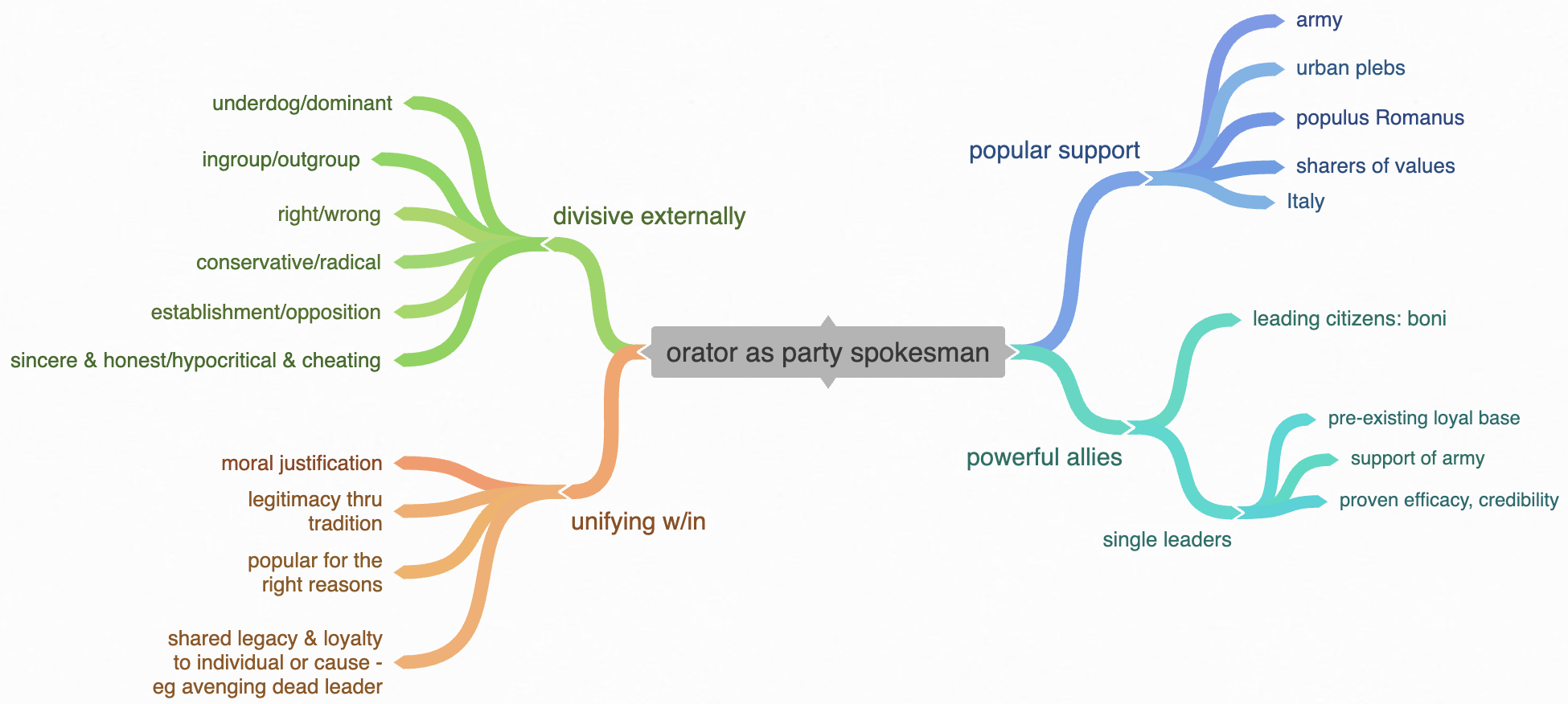

I actually came to love mind maps while I was writing my dissertation. In the revision process, when everything was muddled and I couldn't remember what the point of a chapter was anymore, I used mind maps to re-orient myself, re-organize my thoughts, and decide what were the main points I needed to get across. I used a free tool online (there are many) called Coggle for this:

I'm sure this mind map looks like gibberish – even I don't remember what I was thinking at the time, if I'm honest (it's been more than 10 years!). But the process of mind mapping really helped me to work out the concepts in my head, to articulate and add more specificity to the way I was thinking about certain ideas.

There are a lot of good uses for mind maps in the classroom, and I still think it's fun to make them myself, so get ready for some weird examples.

The psychology of mind maps

Cornell's Joseph Novak wrote a book called Learning How to Learn in 1984, describing how he had struggled to test children's prior knowledge:

During the early 1970s our research program struggled with the problem of making records of what children know about a domain of knowledge before and after instruction. We tried every conceivable form of paper-and-pencil test and found that these poorly represented the children’s knowledge. Interviewing children on how or why they selected their answers showed that many chose the right answer for the wrong reasons and most knew either more or less about the subject than the test question answers indicated.

Novak's solution was to make mind maps with the children instead, where they talked through what they knew and the relationships they perceived between ideas or facts. This turned out to be a much better way for the children to communicate what they knew, and a much more reliable indicator for Novak's research team.

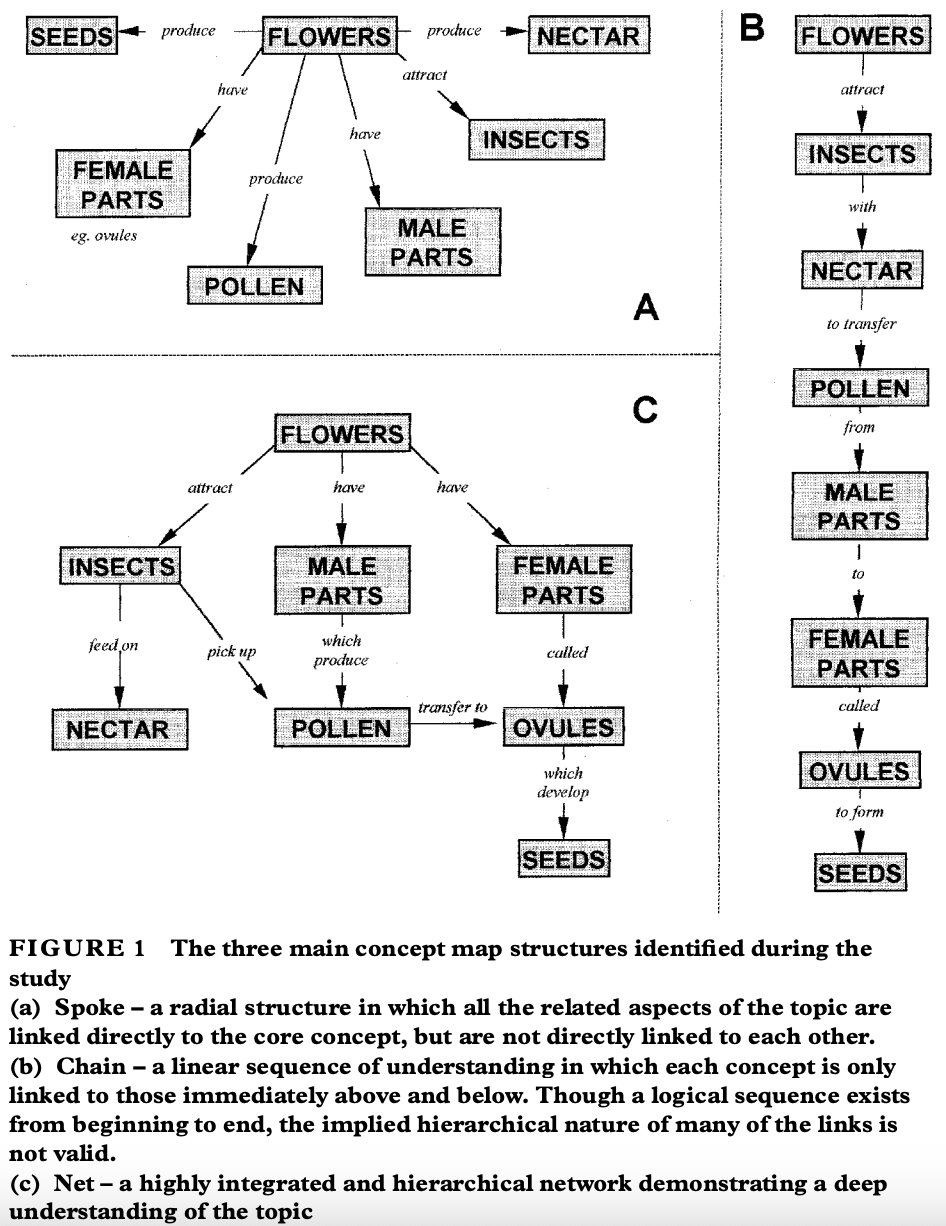

Novak refined a particular type of mind map called a concept map, where the most important ideas came at the top of the map, and the lines connecting ideas had "propositions" or words explaining the relationship. The method was so useful that the pages of Learning How to Learn are full of concept maps – some of them about concept mapping! Mind maps, as opposed to concept maps, usually have central nodes with subordinate terms fanning out, like the one I made for my dissertation.

"Concept mapping" now has a devoted scholarly community all its own (as I discovered to my surprise), including many scholars working with the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition in Florida where Novak served as Senior Research Scientist, which offers a digital "CMap" tool. Concept mapping turned out to be a wonderful assessment tool in STEM (although time-consuming to grade), because students could go beyond regurgitating facts and actually document meaningful learning that had taken place. It also turned out to be a great collaborative tool: groups could map out the work they planned to do together or important concepts, and the process of mapping drew out participation and contributions from all the group members, in a way that helped everyone to get on the same page. Anita Hall and Robyn Havens championed the use of concept mapping in nursing as well, for understanding disease processes and clinical data as well as planning out presentations.

Not all concept maps are created equal. That's what makes them a good assessment tool: you can see how complex (or not) the mapper's conceptual understanding is. In a 2000 article, a team from Kings College London illustrated the difference. The "A" map, a spoke pattern, only shows simple associations. The "B" map, a chain pattern, shows an oversimplified or misleading linear sequence. The "C" map is the best and most complex.

Mind maps in the classroom

In my mind, there are three great ways to use mind maps in the classroom:

- mastering a lot of new information in an intro class

- going beyond rote learning

- planning an essay, paper, project, or complex assignment, especially in a group

- Mastering a lot of new information in an intro class

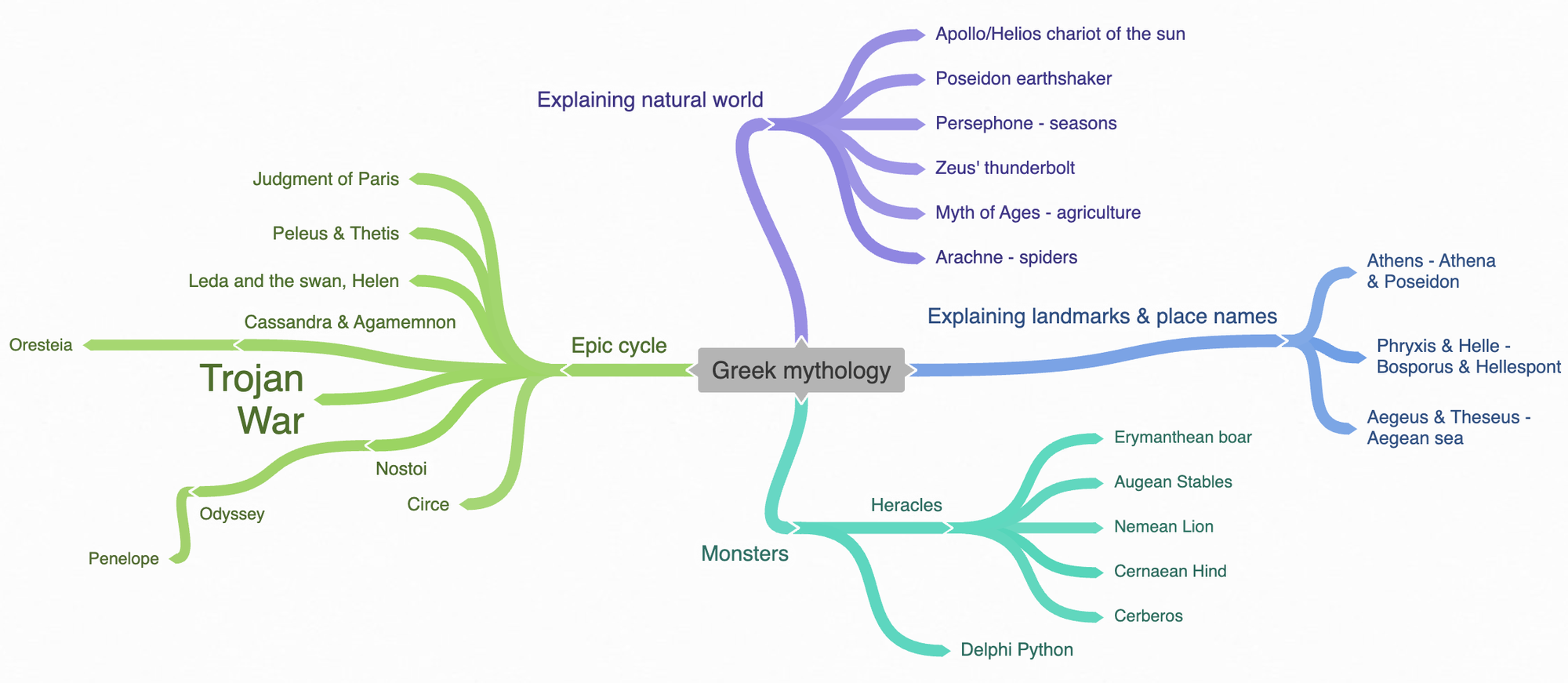

I always used to hear Greek Mythology students complain: "no one can possibly remember all these weird names and who they are!" One way to help assimilate a lot of new information is to sort it into categories in a mind map.

There are many right ways to do this, but the point is that you have to think about each myth and what makes it similar to others, and that kind of thinking makes you more likely to remember the myth.

One option here is to provide students with a partial mind map, where you've already added some labels – often called a graphic organizer. You can even provide this at the start of a lecture, so that they're filling it out as they go. You might provide a list of terms that should end up in the mind map. This kind of support makes students less likely to get it wrong, but also significantly reduces the complexity of their task and requires less mental effort on their part, which means they won't learn as much.

- Going beyond rote learning

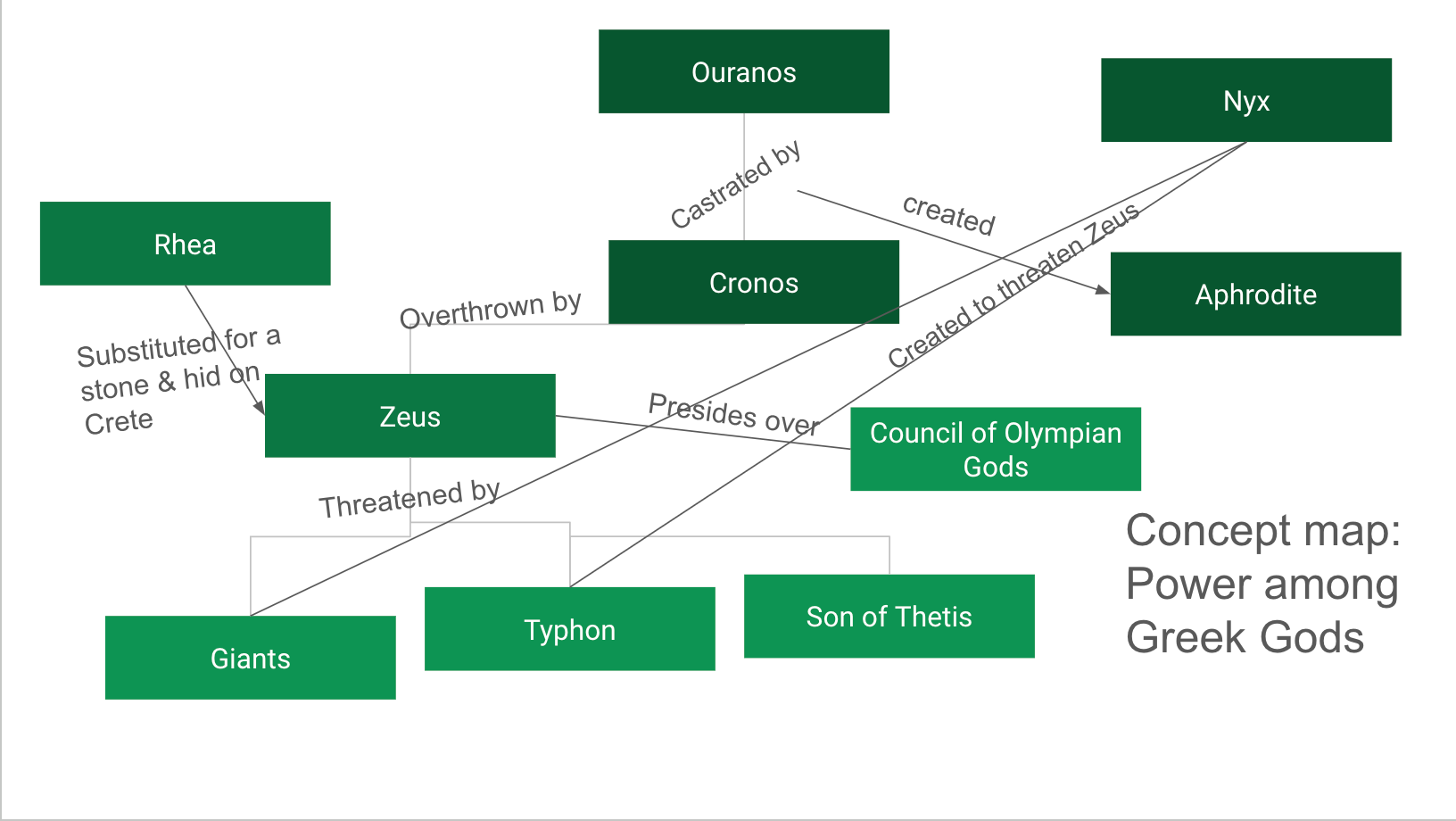

Deep learning isn't just mastering a large number of facts, but understanding relationships, processes, and hierarchies. If I were to ask Greek mythology students who the king of the gods is, that's pretty simple. But if I were to ask how kingly power was transferred or won among the Greek gods, that's a more complicated question. Having students create a concept map to answer this prompt might show you how well they've really understood:

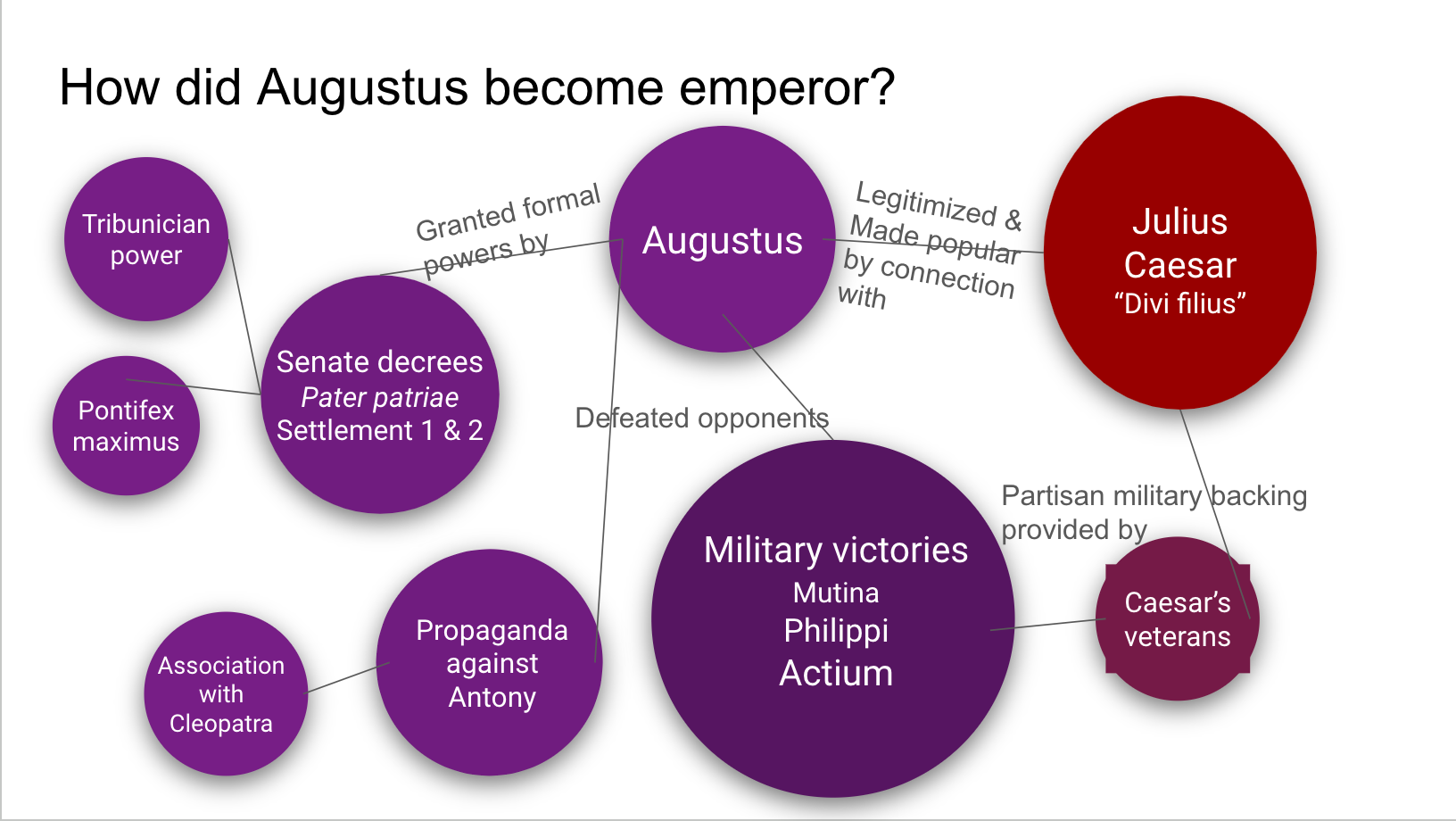

Historical questions or problems can also be expressed in concept maps:

There are so many bad, reductive ways to answer a question like "What caused the fall of the Roman Republic?" Asking students to answer in the form of a concept maps primes them to think about a complex answer with lots of factors at play.

These are exercises that students can do in class, but they could also submit mind maps as an assignment. Some students might find it easier to express their ideas graphically (or orally) than in written form, so you may get better work from all your students by allowing a range of submission formats.

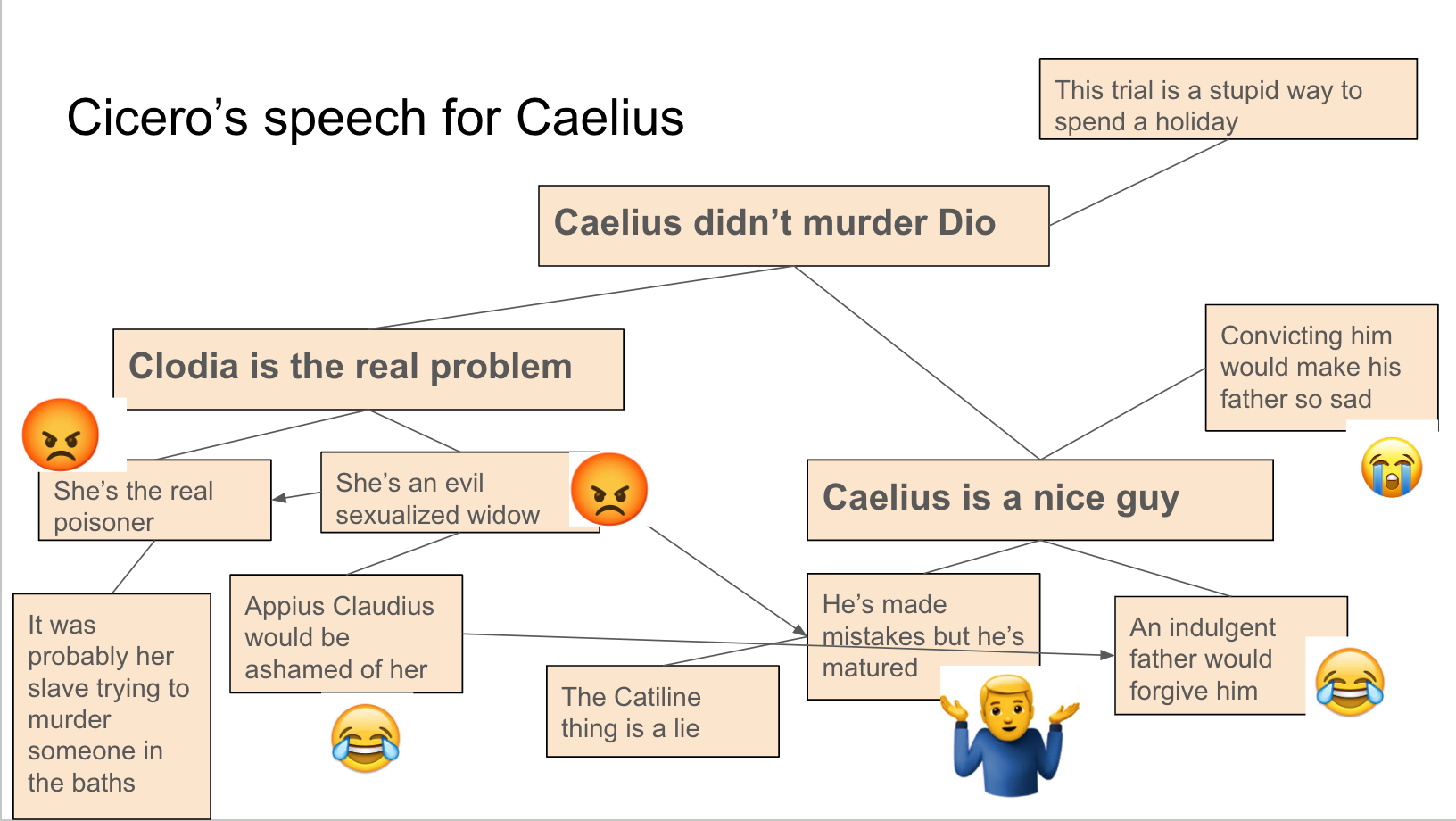

(Incidentally, I made these concept maps in Google Slides. In the "Power among Greek Gods" and Pro Caelio maps, I made text boxes, added an outline and fill color, and connected them with lines. In the Augustus map, I inserted a pre-made diagram and edited it. Here's a tutorial for another way to do it.)

- Planning an assignment

There's no reason to use mind mapping only for course content; it's also a great planning tool for coursework. Novak's team taught corporations to use it to scope out group projects and roles, and to support collaboration by helping a group of people to articulate their assumptions, broaden their thinking, and get on the same page.

A political science professor and I developed a mind mapping activity for students to help them choose project topics: they all come in with overly broad topics, and a mind map can help them to break down that broad topic into manageable parts. One of those subtopics usually makes a workable assignment topic. A mind map about Cicero's speech for Caelius (mapped above) could yield plenty of paper topics: the representation of fathers, the representation of widows, the invocation of a Roman festival, using Clodia to distract everyone from Caelius' guilt, etc.

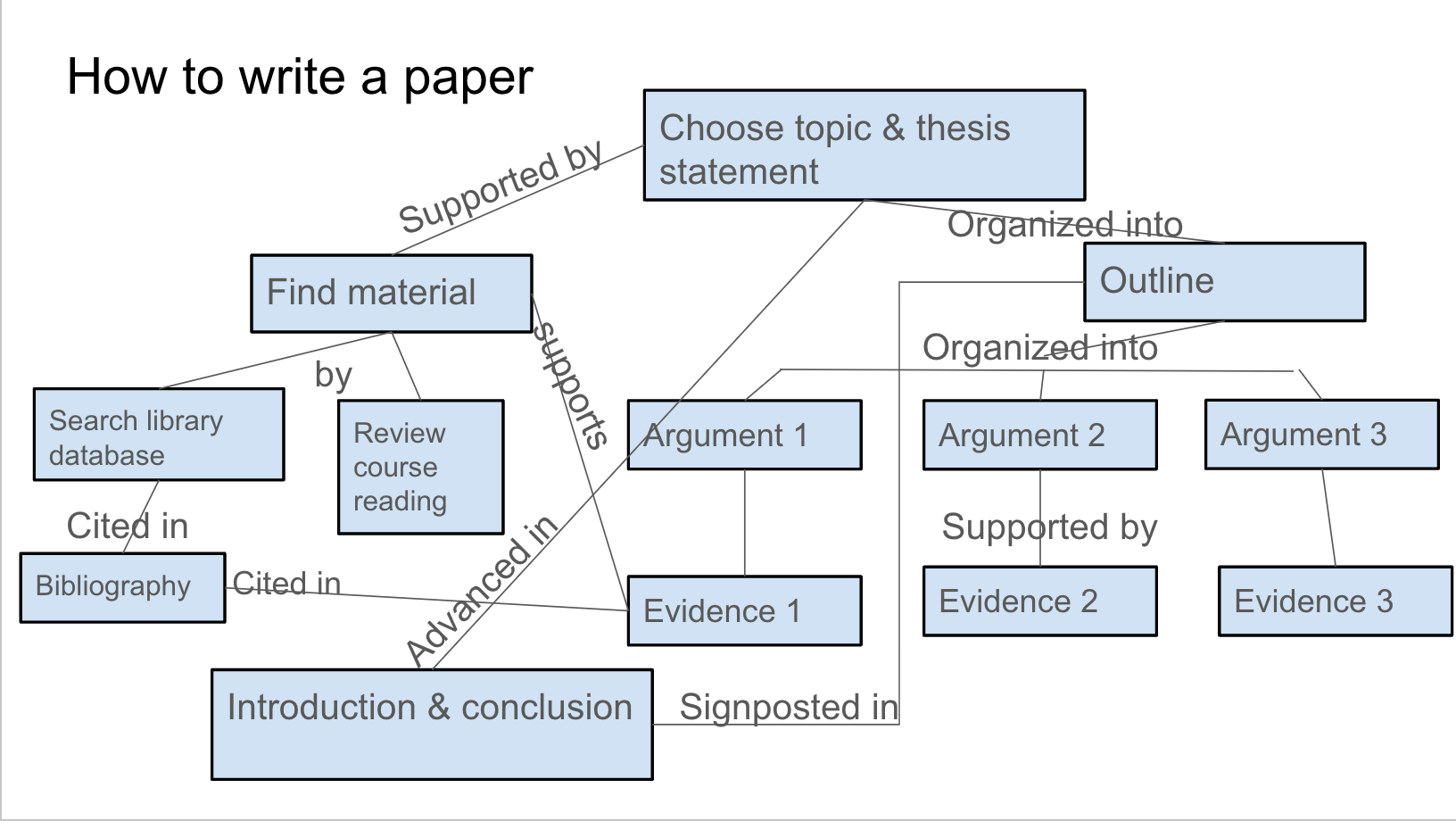

I can also imagine students mapping out the process of writing a paper – which is a lot more than just writing! – so that they can plan their work accordingly:

The takeaway

Frankly, when I read Novak's concept maps, they didn't make much sense to me until I studied them carefully; reading someone else's concept map is hard. It's making a concept map that really facilitates learning and clarifies thinking.

In any case, making mind maps or concept maps is a great activity to bring to the classroom for several reasons. It's a nice change of pace, but it also helps learners to review what they know, to think about it in a new way, and to put it to use in creative and new ways. That makes them much more likely to remember what we're teaching them, but it also makes them likely to go beyond basic facts to reach new conceptual understanding.

A couple of caveats:

- an effective concept mapping exercise begins with a clear, thought-provoking prompt

- don't assume your students know how to use the technological tool you've chosen for concept mapping - provide instructions, even a screen recording of how to make one

Further reading

For a deep dive on really colorful mind maps: Buzan, Tony, and Barry Buzan. (1996.) The Mind Map Book: How to Use Radiant Thinking to Maximize Your Brain's Untapped Potential. Penguin.

Jennifer Gonzalez, "The Great and Powerful Graphic Organizer." Cult of Pedagogy blog, 2017.