Why we should all be teaching Cicero's "Pro Marcello"

In a state of uncertainty, there are difficult ethical decisions to be made. Cicero did not take the most ethically rigorous stance, but I think that makes him more interesting to think with, especially now.

I know what you're thinking. Pro Marcello? What on earth is that?

Cicero's speech "On Behalf of Marcus Claudius Marcellus" is not one of his greatest hits. If "In Defense of Caelius," "In Defense of Milo," or "Against Catiline" were chart-topping singles, the speech for Marcellus is decidedly a deep cut, a B side. (He published almost 60 surviving speeches, and they can't all be famous.) Nonetheless, the times we're living in (o tempora! o mores! Sorry, reflex.) mean that now is the time to read this speech very closely indeed.

Let's set the stage.

It's September of 46 BCE, and Julius Caesar has recently been elected by the Senate to the office of Dictator for the third time. The office of Dictator is a sort of emergency powers situation in the Roman Republic, except that Caesar had been granted the office for a wholly unprecedented period of ten years.

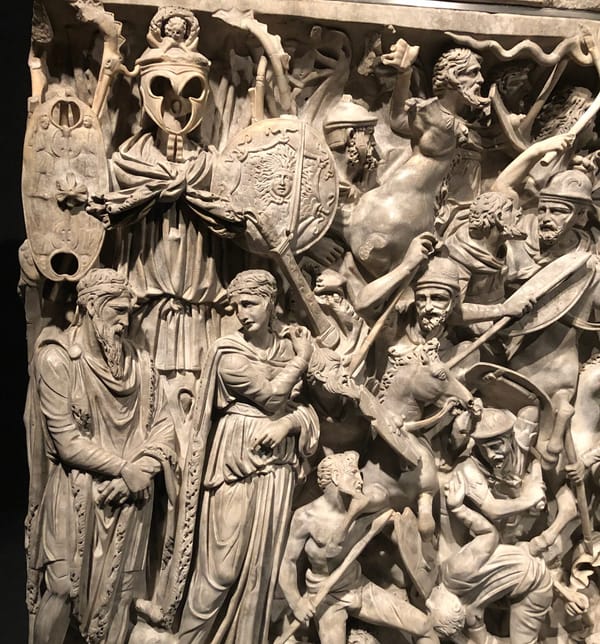

Caesar has crossed the Rubicon, cast the die, beaten Pompey the Great in the Battle of Pharsalus to become the last surviving member of the First Triumvirate, and beaten his opponent Cato the Younger in Africa (both died after the decisive battles and not in them, but that's another story). He has had his affair and a child with Cleopatra. He "came, saw, and conquered" in Pontus, and now he's returned to Rome a conquering hero. He doth bestride the narrow world like a colossus, i.e. stomp around like a giant while the rest of us try not to get smushed under his big feet. He's a little less than two years away from assassination on the Ides of March in 44 BCE (46 was a long year).

Cicero, a preeeminent lawyer/politician/public intellectual, is sixty years old. He is over it.

He had tried to sit out the civil war between Pompey and Caesar entirely. He had written passionately about the Republic as the right system of government for Rome, a government in which (by his account) the Roman people were sovereign over their affairs and their empire, free to elect officials and vote on some legislation, under the (ideally) wise pastoral guidance of the Senate. No extremely powerful individual, Pompey or Caesar or anyone else, was part of that system. As he described in his letters to his friend Atticus (8.7 in particular), Cicero had judged that Caesar would probably win an armed conflict, but Cicero didn't want to do what was practical or expedient – namely, simply declaring his allegiance to Caesar. Unfortunately, Caesar had sent agents to his house (Att 8.9a) and told him he'd better choose one side or the other. Cicero then chose to align with most of the rest of the Senate, who had sided with Pompey. Those senators were no angels (electoral bribery and embezzlement from the provinces were ubiquitous), and they carried a healthy share of the blame for the unrest that had led to civil war, but they seemed to Cicero to represent the lesser of two evils.

After Pompey's forces lost the Battle of Pharsalus, Cicero surrendered to Caesar, along with many other Senators and pro-Republic figures, including Brutus. After all, apparently the gods wanted Caesar to win. Enough was enough. Caesar, showing the clementia or forgive-and-forget policy for which he became famous, pardoned them immediately. Cicero went home and started writing about rhetoric and philosophy in semi-retirement. He wrote letters to friends grieving the loss of the Republic (and of many of their colleagues), nurturing some hope of restoring institutional stability from behind the scenes. Caesar cajoled him into attending Senate meetings, but when he was called upon, he chose not to speak.

Not everyone was willing to beg Caesar's mercy in order to return to their lives in Rome. Marcus Claudius Marcellus, for example, decided he'd rather live in exile than under Caesar's thumb (on the island of Lesbos between Greece and Turkey, which must have made living in exile a lot more attractive). In his view, there was no way for him to live an ethical life under Caesar's regime. He would not beg forgiveness or apologize for fighting against a tyrant. He would not put himself in a position of being indebted to Caesar's mercy, obliged to help him in the future. He would not participate in a political arena in which Caesar was the most influential participant, because simply participating would show acceptance of that unacceptable circumstance. For him, resistance was the only ethical way, even though he'd be leaving his family and friends and clients without his protection in Rome and removing his voice from the political arena. The same logic had led Cato the Younger to keep fighting against Caesar to the bitter end.

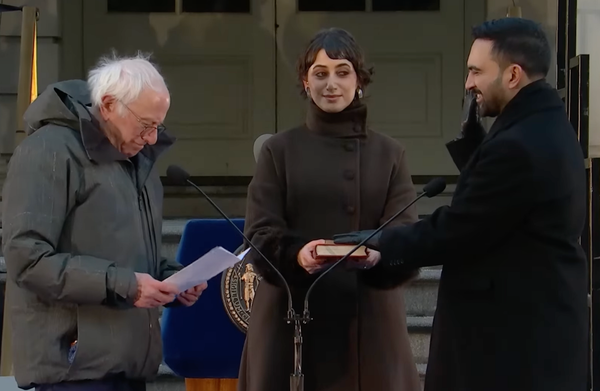

I hope it's starting to become apparent why I think this speech is a good one to think with in the Trump era. Heads of law firms, universities, DOJ units, public health agencies, foreign aid organizations, and other institutions are facing questions of when pragmatic cooperation is ethical. Actually, so are political factions on the left and right and in the middle. Some stay at their posts and cooperate, hoping to be a moderating or normalizing force; some resign and write long, outraged public letters to prove a point, to draw a red line they will not cross. Some want incremental change from the inside; some, believing that change from the inside is impossible or that incremental change is worse than none at all, want a radical overhaul. And at the root of it all is the failure of institutions and leaders to secure the Republic.

So how does this all set up the speech? In 46 BCE, in a meeting of the Senate, Marcus Marcellus' cousin Gaius got down on his hands and knees and begged Caesar to pardon Marcus, to let him come home. Caesar replied to the effect that it was Marcus, not him, who was the obstacle, and that he wouldn't stand in Marcus' way. And in that moment, Cicero decided to break his long silence to deliver what we now know as his speech "On Behalf of Marcus Marcellus." (He wrote down his speeches after giving them, so it's some kind of approximation of what he said from memory. But his memory was very good.)

The speech itself is...unsettling. It can be hard to follow Cicero's speeches without knowing a whole lot about the ins and outs and daily spats and minor characters of Roman politics, but this one (partially but not entirely because Caesar is well-known) is more accessible, and just feels wrong. Most of it is dedicated to an effusive, totally over-the-top praise of Caesar – what ancient rhetoricians would call a panegyric. A classical panegyric is almost always delivered to a king and offers the orator a chance to show off their artistry and originality in inventing new and fanciful ways to praise him. Panegyrics almost never have a place in a Republic. And yet:

No one has a vein of talent so great, no one has such force or capacity in speech or in writing as to be able to recount your accomplishments, Caesar, much less to embellish them. But if you permit me, I will assert this much, that your previous actions can receive no praise higher than what you have earned this day. I frequently imagine, and frequently say so with pleasure, that no comparison can be made between all the deeds of our generals, all the deeds of foreign tribes and powerful peoples, all the deeds of famous kings, and your deeds—not in the size of the conflicts nor the number of the battles nor the geographical range nor the speed of action nor the diversity of the wars. Nor could anyone's feet traverse lands so far apart more swiftly than they have been covered not by your travels but by your victories.

...

There is nothing random about wisdom, no chance in the exercise of judgment. You have conquered tribes of barbarian savagery and countless numbers in uncounted places with overflowing resources; but what you conquered was by nature and condition capable of being conquered. There is no force so great that it cannot be weakened and broken by the strength of arms. But to conquer one's spirit, to check one's anger, to be moderate to the conquered, to raise up an adversary outstanding in nobility, talent, and courage, and not only to raise him up when he is fallen but even to enhance his previous standing--the person who does this I do not compare to the greatest humans but judge him to be like a god.

(Marc. 4-8, from James Zetzel's excellent translation of Ten Speeches by Cicero from Hackett. There's also a translation of it in Dominic Berry's volume of Political Speeches from Oxford.)

How do most readers interpret this? Cicero sold out. He flip-flopped. He bent the knee. He looked which way the wind was blowing, and trimmed his sails accordingly. He is lying about his opinion of Caesar (judging by his letters and other writings about the Republic). He is praising Caesar as a manipulation tactic, to get Caesar to let Marcus Marcellus and other exiles come home, and/or to get Caesar to like Cicero and elevate his position in the new regime. Cicero might also be motivated to extreme flattery by fear that Caesar will eventually punish him for his previous opposition and ongoing lack of enthusiasm. Maybe Caesar's cronies even drafted the speech and told him he had to deliver it. In short, the dynamics that one might speculate about when watching coverage of many public Trump cabinet meetings.

But a few hundred years later, a scholar in a monastery compiling commentaries on some of Cicero's speeches wrote about a different interpretation. Most people, he wrote without explaining any further, think that the speech is "figured," an example of a technique called oratio figurata. In some rhetorical theory treatises, oratio figurata is described as praise that goes so far beyond the boundaries of propriety that it starts to make the audience feel resentment or violence toward the person being praised, instead of admiration. It is supposed to be particularly useful in situations where a tyrant is likely to respond to outright criticism or opposition with violence, perhaps calling it "sedition." After all, the orator hasn't actually said anything offensive; in fact, the tyrant and his supporters are likely to enjoy the speech because they take a straightforward, literal interpretation and miss the subtext. It's the tyrant's detractors who get it and hear a totally different message. (I'm boiling this down quite a lot. I did a whole year-long postdoc fellowship on figured speech in the Netherlands, believe it or not.)

So if you're Brutus, sitting in the Senate and listening to Cicero's speech "On Behalf of Marcus Marcellus," do you come away plotting Caesar's assassination? And do you think that's what Cicero was trying to convince you to do?

That's what I asked my students when we read this speech in a seminar on "Individual and Society in the Ancient World." We'd read examples of civil disobedience (Antigone and Lysistrata), and of heroism and exceptionalism (The Iliad), before turning to a really thorny topic: compromise and concessions. When is the right time to compromise, to yield to majority rule or experts or authority figures or institutions, and when should you stand your ground? How do you weigh doing the right thing against protecting your family from upheaval, or continuing to fulfill your social responsibilities and your responsibilities to your country? Marcellus and Cicero came up with radically different answers to that question.

Cicero's speech was so florid and excessive in its praise that my students cringed. They had grown up as citizens of a constitutional democracy, so they hadn't often heard people talk like that about political figures (I probably prompted them to notice and reflect on this reaction and how they perceived Cicero as a leader in a pre-class written assignment). Then in class, I assigned one group the role of Brutus, another the role of Caesar, and another the role of senators who owed their careers to Caesar. How would each of these audiences interpret the speech? Would Brutus think it was oratio figurata meant to incite hatred of Caesar, maybe even an assassination attempt?

Take a look at how Cicero actually addresses the danger that Caesar will be assassinated, apparently a suspicion Caesar had expressed before:

I come now to your most serious complaint and most horrible suspicion, which you must provide against, but no more you than all citizens, and particularly those of us who have been preserved by you. Even though I expect it is false, I will never make light of it: to look out for you is to look out for ourselves. If one must err in one direction or the other, I would prefer to seem excessively timid than not sufficiently prudent.

But who could be so insane? Someone close to you? But who is closer to you than people who received from you the safety for which they had no hope? Or one of your followers? I can't believe anyone could be so crazy that he wouldn't put before his own life the life of the man who led him to the summit of his wishes.

Or if your supporters have no thought of this crime, are precautions necessary against the plans of your enemies? But who? All your former enemies either lost their lives through their own stubbornness or kept them through your mercy; either your enemies have perished or the survivors are your most devoted friends.

But since men's minds hold such dark hiding places, we should increase your suspicions; at the same time we will increase your watchfulness. Who in the world is so ignorant of the circumstances, so inexperienced in public life, so empty of thoughts about both his own and our common safety as not to understand that his own safety is a part of yours, and that the lives of all depend on your life alone? Night and day you are in my thoughts, as you ought to be; I fear the mischances that affect all humans, the uncertain outcome of health, and the fragility of our common nature. It gives me pain, when the commonwealth ought to be immortal, that it rests on the soul of one mortal man.

(Marc. 21-22)

Is Cicero trying to sound genuine in his fear for Caesar's life, or ironic? Or both at once? If his priority is averting further conflict, maybe he's decided that Caesar's survival is the best chance at stabilizing a peaceful state. But having the safety of the commonwealth rest on the soul of one mortal man is precarious and decidedly anti-Republican – and Cicero has spoken and written an awful lot in defense of the Republic before. What is he up to? The detective work here is a great exercise in reading between the lines – it's a political speech, not a work of fiction, so the orator is certainly working toward a definite goal or strategy of some kind.

There is a third possibility, in between straight bootlicking and ironic figured speech. The ostensible point of this speech is that Caesar pardoning Marcellus is actually a much bigger deal than the residential status of one man. Pardoning Marcellus, Cicero posits at the beginning of the speech, is a symbol of Caesar's intention to restore the autonomy of the Senate and thus the normal functioning of the Republic, the first step on the road back from autocracy to freedom:

I believe, my fellow senators, that the return of Marcus Marcellus to you and to the commonwealth preserves and restores not just his voice and influence but mine, for you and for the commonwealth. ...My old way of life had been closed off; you, Gaius Caesar, opened it for me, and for all of us you have raised up a signal of hope for the commonwealth. In granting Marcellus to the senate and the commonwealth, particularly after recalling his injuries to you, you showed everyone what I had already learned in connection with many people (not least myself, that you place the authority of the senatorial order and the dignity of the commonwealth ahead of injuries to you or to suspicions you feel. (Marc. 2-3)

And he returns to that idea at the end:

This, then, is the part that is unfinished. This is the action that remains; in this you must toil to reconstitute the commonwealth, and you must then take delight in its great calm and order. (27)

To recap, Caesar, with Gaius Marcellus on his knees in a meeting of the Senate begging him to allow Marcus Marcellus to come home, answers with some irritation: "Sure, I guess – he's the one who chose to be in exile anyway." And here comes Cicero, who has not spoken before the Senate for five years, practically putting on an impromptu parade to celebrate that lukewarm comment, as the dawning of a new restoration of the Republic. Maybe he thinks that if he makes a big enough deal out of this, maybe if he lays the praise on thickly enough, he can actually push Caesar into making the restoration of the Republic his new political priority. Maybe this is how he thinks he can make change from the inside.

Ultimately, Caesar does not restore the Republic, and Marcellus never comes home – a Caesarian partisan assassinates him on his way to Rome. But Cicero couldn't have known what was going to happen. He couldn't have known if Caesar was going to move further toward clementia and republicanism, or toward autocracy and proscriptions and more civil or foreign wars. It's not clear if Caesar knew himself. And no one could have known Caesar would be assassinated.

Dictators don't live forever. But neither do Republics. I've always been fascinated by this period because in retrospect we think of it as "the end of the Republic" and the beginning of the period when Rome was ruled instead by emperors, but they couldn't have known that's what was happening at the time. In that state of uncertainty, there are difficult ethical decisions to be made. Cicero did not take the most ethically rigorous stance, but I think that makes him more interesting to think with, especially now.

Related thoughts

I took the quotations from Marc. in this post from Cicero: Ten Speeches, translated by James Zetzel. Hackett, 2009. Also available in a low quality scan on Archive.org.

If you were to read the first chapter of my book, you would find more about Marc. there too.

Incidentally, in HBO's Rome, Brutus actually gives a speech to the Senate that seems to me to borrow extensively from Cicero's "On Behalf of Marcus Marcellus," which I find very annoying.

If you wanted to read some key letters leading up to the civil war, try Letters to Atticus 7.9-15, 7.21-22, 8.2-3 (8.3 lays out a lot of his deliberations), and 8.9a-11, including some enclosed letters to Pompey.

For Cicero's letters to friends (Ad Familiares) after Pharsalus, try 7.28 to Manius Curius, 9.16 to the Epicurean (and epicure) Papirius Paetus, or 4.3 and 4.4 to Servius Sulpicius Rufus, which also describe the speech for M. Marcellus.