Teaching about history: not just names, dates, or "one f-ing thing after another"*

When or if we do teach history, we'll be doing a lot more good if we're giving students opportunities to practice historical thinking, to develop historical literacy.

Everyone knows what history is until he begins to think about it. After that, nobody knows.

—Alan Griffin

Note:

Alan Griffin, “History,” in World Book Encyclopedia, 1962 ed. (Chicago: Field Edu- cational Enterprises Corporation, 1962). Griffin begins his entry on history with this observation, attributing it to “a great authority,” presumably himself.

From Keith C. Barton, and Linda S. Levstik. 2004. Teaching History for the Common Good. Routledge.

Apparently, most children (and probably a lot of adults) think that to get the most accurate history of an event, you just need to talk to someone who was there, but who isn't biased. If that were true, ancient history would be doomed from the start! But more to the point, this is also a misconception that profoundly undermines people's ability to understand the world around them at all, even in the present.

Take the Covid pandemic. Imagine, a few years or decades from now, that a fresh-faced school kid down the block asks to interview you about it for a history class. Where would you start? Where would you end? What would you include? What would you leave out because it's "not important"? What sources of information or pieces of evidence would you rely on, if any?

What do you think would be relevant for a history project? Do you think your response would match what's in the kid's history textbook?

What might you include that you did not personally experience, and why? Would you tell them to talk to or read something else to complement your narrative?

What if they asked you what caused the Covid pandemic? What would you say? How many causes would you list? Would the student think you were "biased" or untrustworthy based on your answer?

And if this happened decades from now, what do you think you might know then that you didn't know in 2020, or now? Would your history of the pandemic extend to 2026? What would that chapter be called?

There are plenty of wrong answers in history, but there are also infinite right answers. The same story can be told – i.e. information about the same people and events can be incorporated into narrative – very differently from different perspectives, for different audiences and purposes, and at different scales. (I went crazy for Hayden White's Metahistory and Quentin Skinner's articles about this in grad school.) And that information can be winnowed from a wide variety of objects and texts, no matter how biased – which is good news for historians, because while some sources are more biased than others, there's no such thing as an unbiased source. London education scholar Peter J. Lee writes: "It is only when students understand that historians can ask questions about historical sources that those sources were not designed to answer, and that much of the evidence used by historians was not intended to report anything, that they are freed from dependence on truthful testimony."

Learning history in an academic setting (as opposed to the many other settings in which people ordinarily learn about the past) isn't just about learning what happened in the past; it's about learning how to find out and understand what happened, and how to describe what happened. In other words, it's about developing historical literacy, a.k.a. historical thinking.

While I was reading about approaches to teaching history, I found myself adding over and over to a running list of thought experiments like the one above that I could have incorporated into my Roman civ lectures. I've written before about how I didn't incorporate as much active learning or retrieval practice into my lectures as I now realize I should have, simply because I didn't know any better at the time. But I loved posing questions like these in seminars, and I imagine now posing a "thought experiment of the week" or something in lectures too, a Socratic moment to challenge preconceptions and get students thinking about how they know what they know.

One of the benefits of learning about the past is that you come to realize that things haven't always been the way they are now. Humans haven't always lived under the regimes of patriarchy, capitalism, or white supremacy. "Western civilization," insofar as it exists, hasn't always been a thing. People haven't always gathered in cities or large nation-states, or used agriculture to sustain themselves. Monotheism hasn't always been so popular. Technological progress and economic growth have not been constant, and in fact have sometimes regressed dramatically. Not all societies have extracted natural resources in a destructive or unsustainable way. "Developed countries" doesn't always mean the same places, nor does "developing world." Not all maps look the same. Our status quo is the result of human decisions, fashions, accidents, power dynamics, and incentive structures. And once you realize that, it opens doors to think about how things could be different. That's true of the discipline of history or classics itself, too; scholars haven't always used the same methods or tools, or produced knowledge the same way, or followed the same conventions. That, itself, is worth talking about in a history class.

In fact, humans haven't always paid tax or tuition dollars to institutions to educate children, and those institutions haven't always taught history.

Abolish history courses?

In 1967, Edgar Bruce Wesley, a prominent thinker in education and particularly in the development of social studies as an educational discipline, wrote for the Phi Delta Kappan: "Let's Abolish History Courses." "For most students," he wrote, "courses in history close rather than open doors to the past. The content seems to bring answers to unasked questions, to supply materials that one does not need, to explain that which has not yet troubled the reader, and to satisfy where there is no curiosity." Instead, he proposed, we should just work history into every other subject whenever it's relevant. "No teacher at any grade level, however, should teach a course in history as content. To do so is as confusing, unnecessary, frustrating, futile, pointless, and as illogical as to teach a course in the World Almanac, the dictionary, or the encyclopedia. The content of history is to be utilized and exploited—not studied, learned, or memorized."

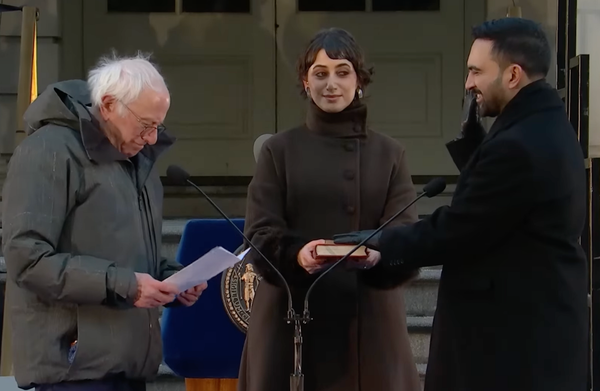

Wesley wasn't that extreme an outlier, broadly speaking. History isn't actually as old an academic discipline as you might think. It dates back to the 1880s. In the Middle Ages, history wasn't named as one of the "liberal arts" or subjects of a well-rounded education. Instead, students learned history as they studied literature and rhetoric. Histories were literary works to be studied. In classical Greek and Roman schools, rhetoric students made up speeches delivered to or by historical figures (an interesting and possibly entertaining pedagogy to try today!), by imagining what calculations and motivations led up to momentous decisions, and historians did the same to add color and vividness to their narratives.

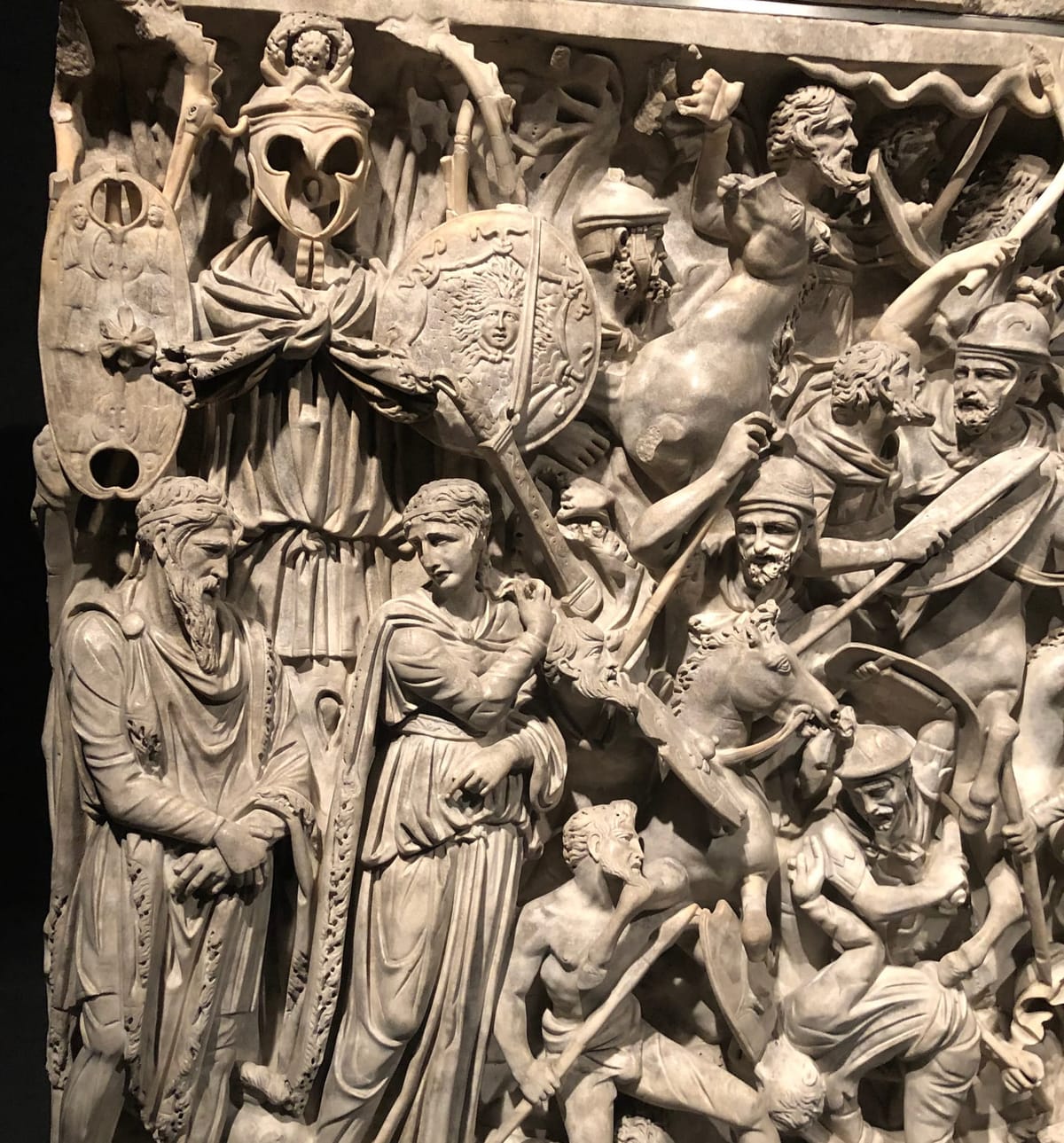

Even though history was not a subject of education per se, we can certainly still see deep historical thinking (as we might call it today) at work in antiquity. Historians back then argued bitterly and endlessly about the proper techniques and methods of discovering what happened in the past, weighing conflicting accounts against each other, identifying causes and turning points, and characterizing human nature to help explain why people did what they did (or, often, why they hated another person, culture, or nation so much). In programmatic statements, ancient historians described their idiosyncratic methods and priorities, identified and defended their criteria for where to begin and end their narratives and what to include or exclude, and berated their colleagues' lack of rigor or discernment. Those are usually the passages you'll read in grad seminars or translate on exams, because they're the most influential passages, the best exemplars of classical learning and reasoning, not to mention a lot more exciting than endless bridge-building (looking at you, Caesar), geographic exegeses, or family trees.

That's the kind of historical thinking that students need opportunities to grapple with in history or civ lectures. Sam Wineburg (founder of Stanford's Stanford History Education Group, now rechristened the Digital Inquiry Group), in his landmark essay-turned-book, “Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts," points out that metadiscourse, i.e. this kind of explicit historical thinking or programmatic statement, is also the first thing to get stripped out of accounts of the past in history textbooks.

So we don't need to teach history. I mean, I love history, but there's a lot of history I don't know, and that's fine. No one can learn all of history (looking at you, Yuval Harari). But when and if we teach history, we should be clear on why we're doing it and what we're trying to teach.

The positive case for history education

When we do teach history, we'll be doing a lot more good if we're giving students opportunities to practice historical thinking, to develop historical literacy. That doesn't mean describing or teaching about controversies or problems in history; it means asking students big questions, and discussing, reflecting on, and probing their responses. I've seen Roman history lectures where the instructor presented conflicting evidence, differing schools of thought, and controversies in the field, and the students totally glazed over, unable to form any concrete idea of what they were supposed to be taking away. Lectures are a good way to deliver basic information; once you've done that, then students will have background knowledge to put to use in more inquiry-based activities.

The American Historical Association put out new guidance in 2016 about the learning goals of history education (if you need a list of learning outcomes for your program, they've got you covered!). But I found more food for thought in an older report. The 1991 Bradley Commission, a group of education scholars and classroom teachers, came out with a strong defense of history education that has informed curricula ever since. Good history education, they argued, could help students to:

• understand the significance of the past to their own lives, both private and public, and to their society.

• distinguish between the important and the inconsequential, to develop the "discriminatory memory" needed for a discerning judgment in public and personal life.

• perceive past events and issues as they were experienced by people at the time, to develop historical empathy as opposed to present-mindedness.

• acquire at one and the same time a comprehension of diverse cultures and of shared humanity.

• understand how things happen and how things change, how human intentions matter, but also how their consequences are shaped by the means of carrying them out, in a tangle of purpose and process.

• comprehend the interplay of change and continuity, and avoid assuming that either is somehow more natural, or more to be expected, than the other.

• prepare to live with uncertainties and exasperating, even perilous, unfinished business, realizing that not all problems have solutions.

• grasp the complexity of historical causation, respect particularity, and avoid excessively abstract generalizations.

• appreciate the often tentative nature of judgments about the past, and thereby avoid the temptation to seize upon particular "lessons" of history as cures for present ills.

• recognize the importance of individuals who have made a difference in history, and the significance of personal character for both good and ill.

• appreciate the force of the nonrational, the irrational, the accidental in history and human affairs.

• understand the relationship between geography and history as a matrix of time and place, and as context for events.

• read widely and critically in order to recognize the difference between fact and conjecture, between evidence and assertion, and thereby to frame useful questions.

If these skills were more widespread in our society, what a wonderful world that would be! However, learning history doesn't help students to do any of that, on its own; educators need to give students prompts and space and support to do it. Instead of (or perhaps before) offering a range of different perspectives on the Augustan Golden Age (peaceful or oppressive?), the fall of the Roman Republic or Empire (when? why?), or some other major moment in Roman civ, look for ways to get students to start generating their own questions and ideas first.

Thought Experiments of the Week

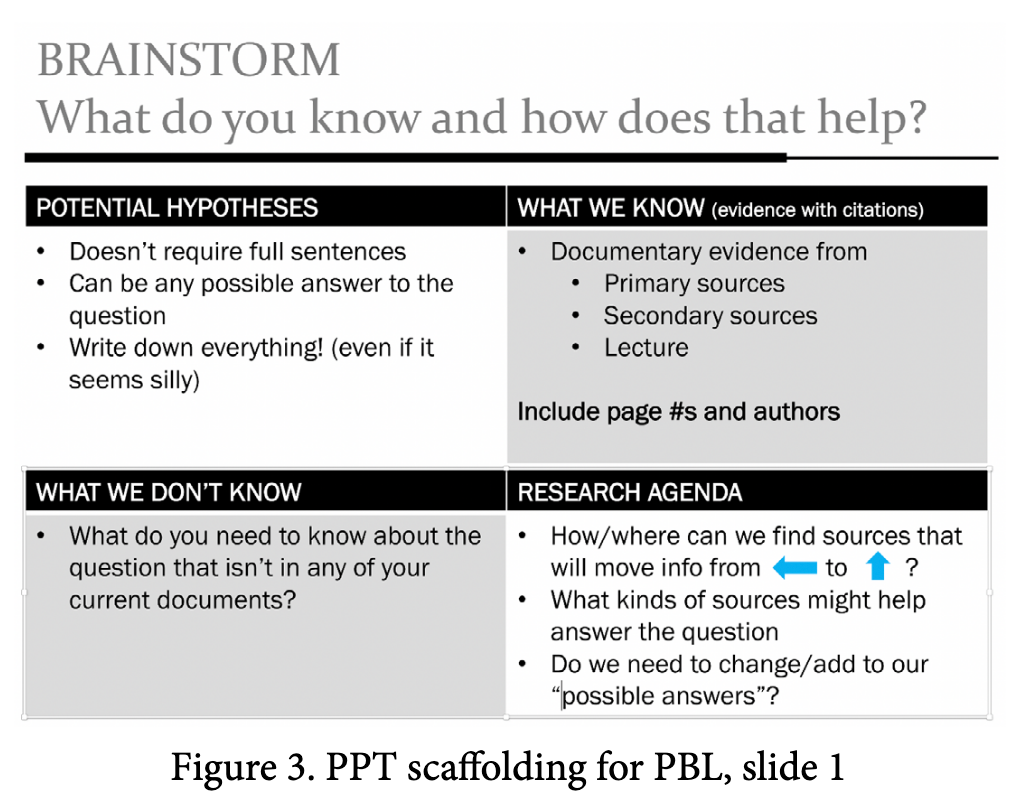

Active learning breaks in history lectures are a great and fairly easy way to incorporate more historical literacy skill-building into a course. A team of medical school educators experimented with a series of activities to develop historical thinking in lectures based around problem-based learning (learning by thinking through complex, discipline-specific real-world scenarios), and it's a framework that you could use to get students to think through any new topic:

But here are some more historical thought experiments I might also throw at students, along the lines of the questions I posed at the start of this post:

More general:

- What history books could yesterday appear in? What stories could it be a part of? (include sports biographies, art periods, food or wellness trends, economic trends, people born today, etc)

- What period of history are we living in? When did it start? How do you know?

- 50 years from now a high school student down the street comes to you and says I’m doing a social studies presentation about the US invasion of Venezuela in 2026. You were alive then, what happened? What do you know? What don’t you know that would be helpful? What would you tell the student to read or watch or search for? What background do you think you would share, to help them understand the moment? If they didn’t believe you, what evidence would you offer them? What objects (no limit on size) would help them to understand what happened?

Specific to Roman history:

Less knowledge required:

- Find a picture of something you associate with Roman history, and paste it in a slide labeled with your name. Each student will explain what they're thinking as we scroll through the slides together (a way to gauge existing knowledge and perceptions).

- How do you think the average person on the street got to know about the event or person we're studying? Generate a list of possibilities. What do you think they thought about it? (How are you imagining the "average person on the street"?)

- If you were writing a history of this event and you could get camera footage from one person at one time to help you, who/when/where would you choose? Reflect on what information you would gain about the event, and what information you wouldn't get – broader understanding, hindsight, alternative perspectives, etc.

- What did people in this time period know that we don't, in this room?

- In a group, draw 5 facts about a person or event at random, then generate a brief historical narrative based on those facts. Then the groups will compare their narratives to see how the same facts can produce very different narratives depending on selection or the survival of evidence, and to see if some missing facts disprove or complicate the picture as they narrated it.

- Give students an overtly biased source (the Second Philippic, the Apocolocyntosis, something like that) and ask them to make a list of all the things they can learn from it about Roman civ, or all the evidence they can get out of it, despite its bias.

More knowledge required:

- Write a speech by a historical figure at a pivotal moment, as a Roman or Greek historian would; reflect on how you thought about the person's motivations and reasoning, and whether/in what ways you might have projected your modern perspective onto the person, or what modern experience you've used to understand the ancient context.

- Generate counter-examples that complicate or disprove an over-generalization about Roman history (perhaps generated by an LLM).

- Brainstorm a list of causes for an event or decision, from the plausible to the fantastical. Then vote on each one to see if there are at least a few people in the room who think that a reasonable person might believe it, eliminating those that no one finds plausible, and discuss what you think makes an explanation plausible. Then discuss which causes had the greatest impact, and how you can decide. (If this involves an out-of-class assignment or component, you can ask them to offer evidence for each.)

- What did I leave out of this lecture that a different historian would have included? Why do you think I excluded it?

Further reading

Wesley, Edgar Bruce. “Let’s Abolish History Courses.” The Phi Delta Kappan 49, no. 1 (1967): 3–8.

Wineburg, Sam. 2010. “Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts.” Phi Delta Kappan 92 (4): 81–94.

*Note: if you're wondering where I got the "one f-ing thing after another" quote, it's from the movie History Boys. I tried to find the clip on Youtube, but no luck. It's how a beleaguered rugby player answers a practice oral exam question, to the consternation of his teachers.