The Tyranny of Learning Objectives

Inside:

1. A story

2. What is backward design?

3. How did we get here? Some history

4. The takeaway

PS: some other taxonomies

One day during my teaching years at the University of New Hampshire, I found myself in a department faculty meeting - I think it was a curriculum committee, one of my rare service assignments as a non-tenure track lecturer. My colleague leading the meeting announced that we'd been ordered by the dean to identify learning objectives for every one of our courses in the department. His tone, and the response from the room, suggested that this was a cruel and unusual punishment.

A few years later, in the early months of the pandemic, I briefly worked as an instructional design consultant for an ed tech company. Each of us was assigned a group of professors. In my onboarding with the company, I learned that our procedure began with identifying learning objectives for each course overall. Then, in our meetings with the professor over several weeks, we would go through each week or "unit" in the course and identify the learning objectives for that week, and align them with the learning objectives for the course overall. Then we'd map out assignments and tests, a.k.a. "deliverables," aligned to the unit learning objectives.

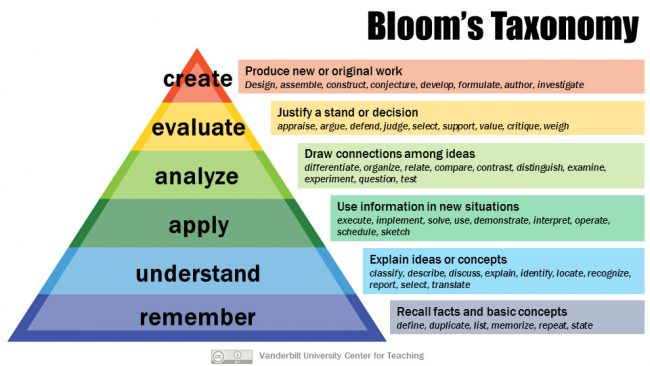

And then my supervisor showed me an infographic that blew my mind:

When I sat in that curriculum meeting at UNH, I had been teaching in higher ed for about 6 years, including my years as a graduate student instructor (at which time I earned a Certificate from the Center for Teaching and Learning for attending pedagogy workshops). At no point had I ever been introduced to Bloom's Taxonomy, which dates to 1956 and was updated in 2001 and represents a larger movement, backed by cognitive psychology, away from rote memorization in schooling. I seriously doubt that I was alone in this, at my institution or in my field, although maybe things have changed since then.

In fairness, Bloom's Taxonomy made immediate sense to me: lower-level courses are more about mastering basic information, but as you get more advanced in a subject, you should be able to do more than regurgitate facts. In Latin, you have to remember vocabulary and noun declensions and verb conjugations at the intro level, but eventually you're also going to have to apply that knowledge in reading. And if you go to grad school, you'd better be ready to analyze texts with complex thinking. So on that level, I didn't really need Bloom's Taxonomy after all.

But in that curriculum committee meeting, it sure would have expedited the process of designating learning objectives for our whole catalog of courses if the dean had simply attached Bloom's Taxonomy to her email about the new mandate. Funnily enough, our administration had failed to align their deliverables with our learning.

In my consulting gig, thanks to my committee experience, I knew that asking professors to identify learning objectives might be taken as an act of war, so I talked around it: what are the top three ideas that you want students to take away from your course? When they show up later in an upper-level course, what should they already know if they've taken this one? As they talked through this, I took notes and used Bloom's Taxonomy to translate what they were saying into the action verbs we needed for our instructional design templates. "It won't be that bad," I promised them.

What is backward design?

The curriculum design method of beginning with your end objectives and working backward to design a course is known (naturally) as "backward design", or constructive alignment, or in a more formal iteration as the Understanding by Design© framework (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). As soon as I learned about it, I wished I had been trained to use it as a graduate instructor, expert in Latin and clueless in pedagogy.

One major player in the world of backward design is Quality Matters, a nonprofit that grew out of MarylandOnline, a consortium of online programs at higher ed institutions in Maryland. From 2003-2006, they used a government grant to develop a rubric for evaluating the quality of courses in higher ed. This rubric was adopted quickly and broadly, and obviously met a major need in the world of online learning. It also satisfies a corporate impulse to systematize, quantify, and standardize (at odds with the messy, human, widely variable world of college student learning) which suited online learning professionals in the business of workforce development.

However, online learning programs are almost completely separated from professors in classrooms into different silos in higher ed, so it doesn't surprise me that this major innovation in online learning did not seem to make it into professors' hands (or those of their grad students).

Until the pandemic, that is.