Uses and Abuses of History Education

History education can establish a shared narrative, a common ground that supports dialogue, deliberation for the common good, pluralism, and the dynamics of a healthy democracy.

As I was reading about history education for my last post, I came up against a major challenge in the field: what's the right relationship between history (specifically, what we learn about the past in a classroom) and our lived present? What is history good for? What practical use is it, if any?

Trained historians get really spiky about popular expressions like "history repeats itself," "those who don't study the past are doomed to repeat it," and the like. Studying the past, they'll tell you, is a really bad way to try to predict the future. Trained historians also find it frustrating when facts from within their specialty get cherry-picked in a reductive way and then used to support tenuous claims about the present, even by very knowledgeable and well-meaning people. (It's especially frustrating when our academic colleagues from other specialties do this with material from ancient Greece or Rome, but we're probably just as guilty of it ourselves sometimes when we study classical receptions...)

In 2022, the then-president of the American Historical Association, James Sweet, a historian of African colonization, diasporas, and enslavement, published a newsletter that went viral for all the wrong reasons (it's now preceded by the apology he issued in response). He critiqued the use of history to speak to the present, which he framed as part of a larger trend of "presentism" in the discipline:

This new history often ignores the values and mores of people in their own times, as well as change over time, neutralizing the expertise that separates historians from those in other disciplines. The allure of political relevance, facilitated by social and other media, encourages a predictable sameness of the present in the past. ...Whether or not historians believe that there is anything new in the New York Times project created by Nikole Hannah-Jones, The 1619 Project is a best-selling book that sits at the center of current controversies over how to teach American history. As journalism, the project is powerful and effective, but is it history?

Sweet wrote that he was also distressed by distortions and whitewashing of complexities in the dynamics of enslavement of Africans – where diasporic populations lived, how other Africans participated in enslavement – and by a more general "idea of history as an evidentiary grab bag to articulate ... political positions." He warned: "When we foreshorten or shape history to justify rather than inform contemporary political positions, we not only undermine the discipline but threaten its very integrity."

Valid points, but the 1619 Project was, at the time, under fire from conservative commentators eager to whitewash American history, a move that took shape in Project 1776 and its uber-patriotic curriculum (which the AHA had condemned). In that context, maybe Sweet could have read the room, and anticipated that his own critique of it wouldn't be well-received.

On one hand, historians ought to aim for neutrality, to imagine themselves into the perspectives of historical actors rather than projecting their own ideas into the past – that's the kind of historical thinking I explored in my last post. But on the other hand, if our own perspectives didn't shape the way we do history, then we wouldn't keep writing new histories. And sometimes our modern experiences help us to realize whose history has been ignored or excised – histories of African enslaved people who didn't write their own narratives, or people writing at that time against colonialism and chattel slavery, for example. No history can include every perspective, but bad histories suppress the perspectives of whole populations and communities.

One additional consideration that I came across in my reading: we're not just historians; we're also educators, and that makes a big difference here. Our students are not historians, and few if any will ever become historians. It's not reasonable to expect them to learn about the past only for its own sake.

My short version of my syllabus day spiel – because I do this at the beginning of every semester – is, one, I introduce myself by saying I’m a professional historian who thinks random historical trivia is pretty much worthless for humanity. They love that one at the beginning. I mean random historical trivia, right? If it’s just a thing that I think is cool and you should think is cool, if you don’t think it’s cool, I have no back-up for why we’re doing this. Right? So to me, that’s not what we do, right? For most people, even people who don’t like history, we use history, right? We tell stories of the past to give meaning to the present. And that matters.

Andy Polk, Assistant Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University, on the Teaching History Roundtable for the Road to Now podcast, 10/13/25

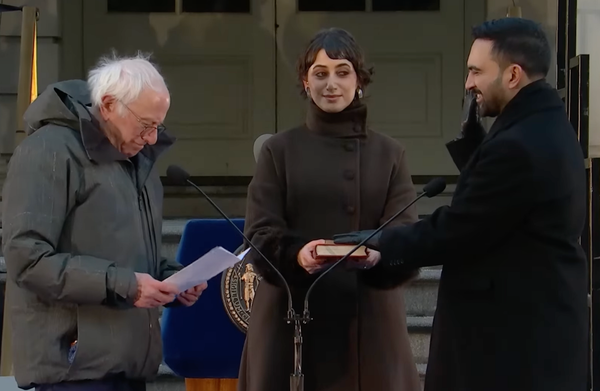

But if what we teach is going to be "useful," exactly what uses is it good for? One answer that's been informing a lot of my work lately is that history education is good for democracy. (I've written here before about the connection between "liberal" education and democratic liberty, and anti-authoritarian education.)

History as civics

When I was working with the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap on civic education projects, one of the recommendations in the roadmap was to combine American history and civics education rather than teaching them as two separate classes. Over a century earlier, in 1899, the newly formed American Historical Association's Committee of Seven made a similar recommendation:

The pupil should see the growth of the institutions which surround him; he should see the work of men; he should study the living concrete facts of the past; he should know of nations that have risen and fallen; he should see tyranny, vulgarity, greed, benevolence, patriotism, self-sacrifice, brought out in the lives and works of men. So strongly has this very thought taken hold of writers of civil government, that they no longer content themselves with a description of the government as it is, but describe at considerable length the origin and development of the institutions of which they speak.

Studying the past can support young people in building the capacity to understand human behavior and form ethical judgments. Learning about the history of civic affairs and institutions in particular will help them to participate effectively in managing the political machinery that is supposed to organize our society.

Keith Barton and Linda Levstik write in Teaching History for the Common Good that an analytical stance (i.e. weighing evidence and interpretations to produce a rational historical account) is the frame usually adopted by academic historians, but is only one of several historical approaches that we should be cultivating in students. Another is the identification stance, learning to connect one's personal, family, or national identity to the past. Sometimes this produces nationalism and chauvinism, but it can also take root in stories of people who are like our students in various ways, or in narratives of inclusion and progress toward justice (more on that below). A third is the moral stance: did people in the past do the right thing or the wrong thing, when it comes to promoting the common good? This is an important question for democratic citizens to be able to answer. Professional historians shun the identification or moral stance, but history teachers in a democracy shouldn't.

Barton and Levstik also dedicate a chapter to the subject of empathy – not in the common sense, but in a specific historical sense of recognizing that people in the past had perspectives different from our own. To understand their actions and decisions, we need to think about those actions from their perspective as much as possible, rather than dismissing them as primitive or judging them by our own culture's values. This kind of empathy serves us well as democratic citizens, too, because it follows a pluralistic principle.

Although most schools talk about democratic citizenship in their mission statements, however, Barton and Levstik found that almost none were actually cultivating these kinds of historical thinking in classrooms. They put this down to teachers' sense of purpose. If your purpose is to get along with colleagues, get through your lesson plan, and go home, lecturing about the past is a great way to do that. It can be a super engaging storytelling session, or not. If, on the other hand, you decide to use your history classroom to develop critical thinking skills or civic dispositions and values, you're more likely to take on the extra work and risk of creating more impactful active learning experiences. But you have to make a choice and find your purpose first.

Patriotism and history education

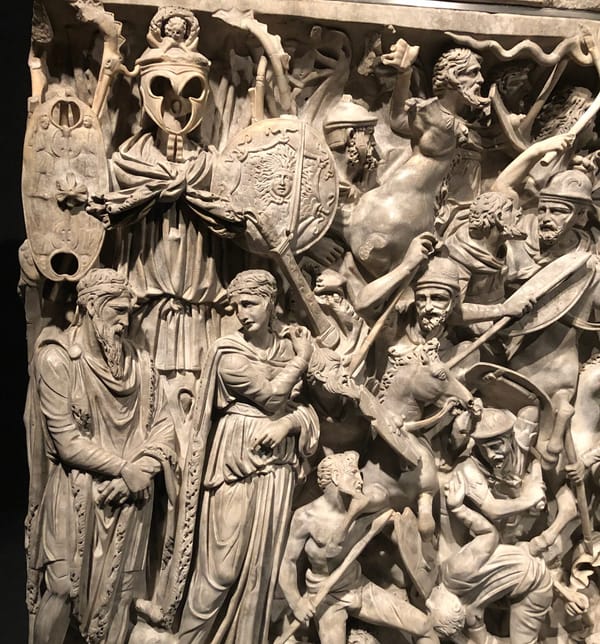

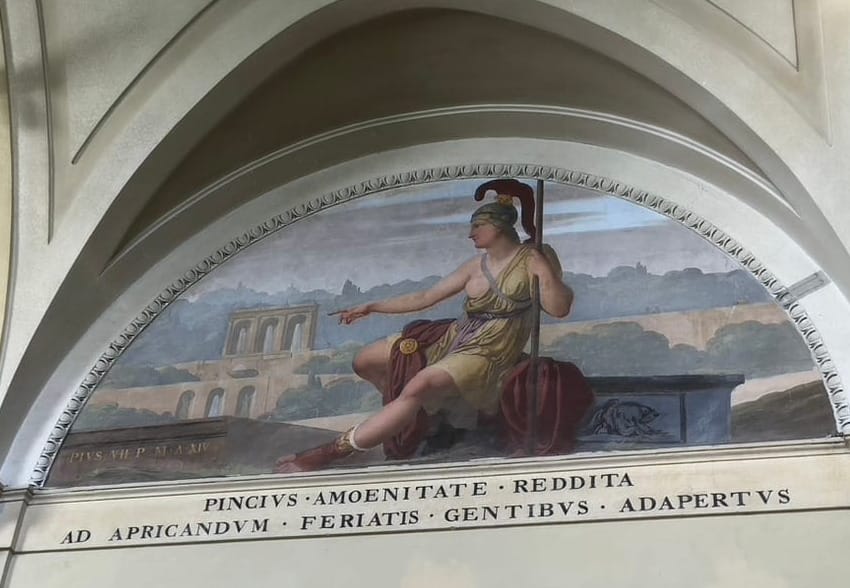

The Educating for American Democracy Roadmap also identifies 5 fundamental design challenges or tensions that teachers and students should grapple with. One is to strive to maintain a constant balance between "civic honesty" and "reflective patriotism." History education shouldn't be about good guys or bad guys. Many history textbooks explicitly or implicitly paint the United States, or Western Civilization or Athens or Rome, as the good guys, sometimes by leaving out hard histories, and that's obviously not good practice. But a history course that ignores or only vilifies them isn't ideal either.

Another design challenge posed in the Roadmap is to tell a "plural yet shared story" about American history, one that's inclusive but also integrated into a coherent whole. A major workforce on history education, the 1991 Bradley Commission composed of scholars and classroom teachers, declared in a similar spirit that:

Unlike many other peoples, Americans are not bound together by a common religion or a common ethnicity. Instead, our binding heritage is a democratic vision of liberty, equality, and justice. If Americans are to preserve that vision and bring it to daily practice, it is imperative that all citizens understand how it was shaped in the past, what events and forces either helped or obstructed it, and how it has evolved down to the circumstances and political discourse of our time.

History education can establish a common ground that supports dialogue, deliberation for the common good, pluralism, and the dynamics of a healthy democracy.

In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning (2018), I read the foreword by Peter Seixas (Philadelphia-educated, taught at UBC), and was sort of flabbergasted. Ever since the 1960s, prominent voices in (and outside) the academy have been working to counter, complicate, and deconstruct dominant cultural narratives, to challenge the (continuing) reign of old white men, to recognize value in every standpoint and perspective, no matter how humble. But in a political climate defined by misinformation and "alternative facts," Seixas writes, maybe our mission has changed. Kids these days know all too well that you can't believe everything you read and that your reality depends on your algorithm, even though they're not always good at applying that insight critically.

I was ready to hate everything Seixas said next:

In the current climate, we cannot afford to toy with separate islands of identity‐based theory, research methods, “epistemologies,” or even “ontologies.” Notions such as women’s ways of knowing and multicultural epistemologies—to the extent that they close down dialogue and debate or, conversely, open up “anything goes” as long as it is deeply held or strongly believed—pose new dangers.

The problem of teaching about historical interpretations, similarly, needs to be examined through a different lens in this political environment. ...Our central challenge will have to focus on helping students to understand the limits of interpretation, the constraints that bind what we say to the evidence that we have, and the importance of defending interpretations that are supported by the weight of evidence, not as just one among many possible ways of seeing things.

In my last post, I summarized some writing on historiography thus: "There are plenty of wrong answers in history, but there are also infinite right answers." Seixas wants us to focus on teaching students to identify and refute wrong answers, with less emphasis on recognizing and holding all the right answers together. But he's also interested in using history education to pull people together, not in the scary nationalist or militaristic way, but in a positive way. As anti-immigrant populist political figures around the world are blaming people of color for the world's ills, he says, perhaps history educators should foreground evidence-based narratives of "progressive opportunity and open democracy" in the past. As communities across the country argue about whose history is "significant" enough to make it into textbooks, "history educators may logically shift their focus to look more forcefully toward fostering the larger narratives that will pull these memories into focus with each other and build toward common understandings." I wouldn't want to say that he's advocating for a new "master" or "dominant" narrative, but maybe a "major" or "public" one:

History educators will thus have to amend our potential contributions to the new political culture. This does not mean shuffling systemic racism, colonialism, homophobia, and gender inequality back into obscurity much less silence, but it does bring with it a call to remember the promises and obligations of democratic rule, the achievements of a peaceful post‐WWII European system, the importance of institutional norms, and, not least, the moral virtues and qualities of character that enable both good leadership and active participation in a democratic state. Most of us have not foregrounded these issues, which were prominent in my own “citizenship education” in the 1950s and 1960s: Now we must.

Seixas is only talking about modern history curricula here, but the same principles might apply to ancient history education as well. Embracing stories of progress, contributions to the common good, elaboration of or struggles to realize idealistic principles, cross-cultural connections, and experiments in self-government or popular sovereignty are available as topics to feature in ancient history too as positive moral and cultural exemplars.

History education for civic healing

Alan McCully, a scholar and history educator from Northern Ireland, conducted research on history pedagogy in his country in the wake of The Troubles. While international education agencies were promoting the teaching of multiple perspectives, particularly in countries emerging from totalitarian rule in the 20th century, he wondered if it was possible to do that in a hyper-polarized country like Northern Ireland, where multiple perspectives on recent history might provoke students to violence or trigger trauma responses. In other countries like Rwanda, Yugoslavia, and Israel, teaching the recent past or even a claimed national past had been done with great caution and sensitivity, if at all.

McCully found that students had acquired quite a lot of knowledge and ideas about the past from their families and communities, but those narratives didn't necessarily match what they learned in classrooms. They benefited from history education that emphasized a shared narrative and a search for truth:

The ‘truth recovery’ process is often conducted through the individual testimonies of those who lived through the time, be they classified as victims, perpetrators, bystanders or survivors. Such biography is very powerful in allowing voices to be heard, and to facilitate redress. …In the post-conflict context, the complementary function of history education should continue to be one of bringing synthesis, criticality, perspective and overview to ‘psychological’ truth recovery, thus preparing young people for the possibility of societal change. It can use the power of individual stories to engage ‘caring’, but also help place the accounts in their broader context and assimilate them into an overview. The synthesis developed is multi-dimensional in that it should accommodate the complexity of bringing together alternative, and often conflicting, perspectives and it should recognize that individual experience is, sometimes, at variance with wider societal trends.

School history formed a sort of stable framework within which students could contextualize and understand individual stories, learned inside or outside the classroom, and to think about them at a critical distance. It also helped them to imagine ways to resolve social conflict in the present and the future. McCully also took an inquiry-based approach in his classroom, encouraging students to research and reflect on sites of remembrance, pamphlets, and different representations of the past to explore their own beliefs and gain critical consciousness.

McCully concluded that “Through its critical skills, the adoption of discursive and participatory teaching methods by teachers and the inclusion of a range of viewpoints for investigation, effective history teaching and learning models democratic practice and, therefore, fosters democratic dispositions in students.” Academic historians may not have any business fostering democratic dispositions or putting history to use to serve a national culture in their scholarship, but history educators in a democracy certainly do. And in this particular moment of polarization and disinformation, that mission may be more vital than ever.

Further reading

Keith C. Barton, and Linda S. Levstik. 2004. Teaching History for the Common Good. Routledge.

Peter Seixas. 2018. Foreword to Metzger, Scott Alan, and Harris, Lauren McArthur, eds. The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.