Reviving academic integrity: Part II - What even is cheating, and why shouldn't we do it?

In Part I of this post, which began as a review of the new book The Opposite of Cheating: Teaching for Integrity in the Age of AI, I summarized some strategies for designing away the conditions that lead some students to cheat. Just as drivers might bend the rules of the road when they're running late or having a bad day or rushing to a hospital bedside, we all make bad decisions in the heat of the moment sometimes. That's a good way to think about many academic dishonesty incidents, say authors Tricia Bertram Gallant and David Rettinger – an ethical slip, not a deadly sin. (Even though I do appreciate my colleague in grad school – Jake Morton, was it you? – telling Roman history students not to cheat off each other in exams: "it's just a stupid exam, don't sacrifice your soul for a stupid exam! Your soul is worth more than a grade!")

That's not to say that cheating shouldn't be called out and penalized, but the penalty need not be expulsion or banishment. Rettinger and Bertram Gallant have a chapter on assessment security with a lot of good tools and strategies for detecting cheating. At the end of the day, they proclaim:

How faculty react to cheating matters. If, as in the first story, you react in the moment in anger and as judge, jury, and executioner, you risk teaching the student that retribution rather than justice is the way to respond to someone who errs in judgment. If, as in the second story, you act like the victim, the wounded, the injured party, you risk teaching the student that cheating or plagiarism is only wrong if the professor cares or it caused an immediate and demonstrated injury or harm. If, as in the third story, you bypass university policy because the student states that they will never cheat again, you risk teaching the student that the remedy for one integrity violation is another integrity violation (that two wrongs make a right) and that if the student says just the right thing, they can escape the justice that might befall others. This last scenario is particularly concerning given that students are differently gifted when it comes to communicating, and communicating in the same language as the instructor, so such an approach would likely primarily continue to advantage the already advantaged. (The Opposite of Cheating)

It's important to write and share a policy you can stick to. I didn't get the sense, as a lecturer, that the dean wanted me making a stink about plagiarism. I put the boilerplate language about plagiarism in my syllabus but didn't do much to enforce it, even when one of my students got caught with study materials in the bathroom during an exam. My colleagues had caught him before and hadn't punished him then, so I didn't feel encouraged to make a stand, and I just let it go. A better course of action would have been to sit the student down and at least have an awkward and unpleasant conversation, which itself discourages future cheating. That might have opened the door to a strategy session to redo work or demonstrate mastery for partial credit (better late than never), and to prepare differently and better for future assessments. But my student and I would have benefited from a lot more institutional support.

A clear, realistic policy must also define what constitutes cheating in your discipline and your course, because many students have no idea.

What even is cheating?

Hiding study materials in the bathroom is a pretty open-and-shut case of cheating, but defining plagiarism and academic dishonesty gets murky pretty fast, even for experienced scholars. If a colleague or grad student recommends a book or line of inquiry that I end up publishing, should I cite or credit them in a published paper? What if my mom or my dentist is the one who makes the recommendation? Scholars don't need to provide citations for "common knowledge," but how common does it have to be, and how would a student know? I didn't usually cite the date of Cicero's letters, but then research for one paper led me to question its conventional dating, so maybe those dates weren't common knowledge after all.

How many words do I have to change in order to paraphrase a quotation honestly? Different disciplines have substantially different norms for citation and direct quotation. And classicists have what may be a unique citation habit in the academy: for primary sources, we use in-line citations of the work (with standardized abbreviations) with a book, section, or line number, so that it doesn't matter what edition you check. We think it's silly to cite a Cicero work as if it was written in 1990, but our colleagues in other fields do it all the time, because they're citing the year of the edition they used. But if we're going to invent our own systems of citation, that doesn't give us much standing to criticize other arbitrary disciplinary practices.

All this is to say, academic integrity is not common sense. We have to define it for ourselves and for our students, and the more explicit and transparent we can be about those rules, the better. The most frustrating cases of cheating and plagiarism are the ones where the student didn't even know they were doing anything wrong, and those cases are very common. Contract cheating sites that offer pre-written papers capitalize on this ambiguity by framing their services as "homework help" or "tutoring."

Collaborating or cheating?

Collaboration is probably the biggest gray area when it comes to "original" work. Students may talk with TAs, other students in the class, frat brothers, parents, mentors, campus tutoring services, or LLMs about their academic work, and they may get helpful recommendations. Is that cheating, or is it allowed? It depends on the nature of the recommendation, and on the nature of the assignment. For each assignment, it would be best to figure out what kind of collaboration will be acceptable from the start, either on your own or as a conversation with your students, so you'll all be on the same page and primed to work honestly. It's best to err on the side of allowing as much collaboration as possible.

That goes for collaborating with AI tools, too. AI tutors and LLMs really can and will offer helpful, individualized support to learners in a broadly accessible way. I don't think they're safe enough (the way Gen AI can escalate mental health crises represents a potentially life-threatening harm to grad students as well as undergrads) or reliable enough, but students are using them anyway – so the situation now calls for harm reduction, as UCLA's Miriam Posner suggests. It's worth discussing with them what kind of uses they plan, and what's appropriate, fair, or "honest." Michelle Kassorla, a great coach on teaching effectively with AI, suggests that it's the use of AI to "reduce friction" and offload cognitive heavy lifting that we should focus on curbing. Her Inverted Bloom's Taxonomy for learning with AI and her repository of AI syllabus policies are useful discussion starters.

Daniel Forrester, author of The AI Fluency Playbook, posted something interesting on LinkedIn last week about thinking of AI not as replacing stairs with an escalator for students, but as helping them walk up an escalator instead of stairs – a support, not a substitute:

Here are 6 AI prompts we're using to help the kids walk up the escalator. Try one out and let me know what you think. I would love to hear some feedback.

1. THE STRUCTURE SKELETON

"Create a fill-in-the-blank paragraph structure for arguing [topic]. Use brackets for where I add my content"

2. THE QUESTION LADDER

"I'm researching [topic]. Generate a ladder of questions from basic to complex that I should be able to answer. Start with 'What is...' and end with 'What would happen if...'"

3. THE "SO WHAT?" GENERATOR"

My main point is [your argument]. Generate 5 different ways to explain why this matters, each starting with a different phrase: 'This matters because...', 'Without this...', 'This changes...', 'This means...', 'This reveals...'"

4. THE CLARITY METER

"Rate each sentence in my paragraph from 1-10 for clarity. For any under 7, tell me what's unclear but don't rewrite it"

5. THE PERSPECTIVE PROMPTER

"I'm writing about [event/topic]. Give me 5 different stakeholder perspectives I should consider, phrased as 'From the perspective of [X], the main concern would be...'"

6. THE WEAKNESS DETECTOR

"Here's my paragraph: [paste]. What's the weakest sentence and what 3 questions should I ask myself to strengthen it?"

Guidelines like these will help students to use AI tools thoughtfully and ethically – but it's worth discussing with them what ethical use means, and what the criteria should be.

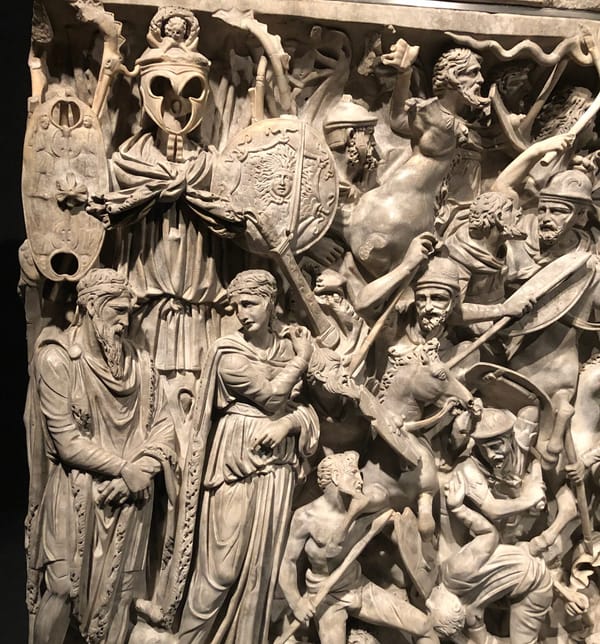

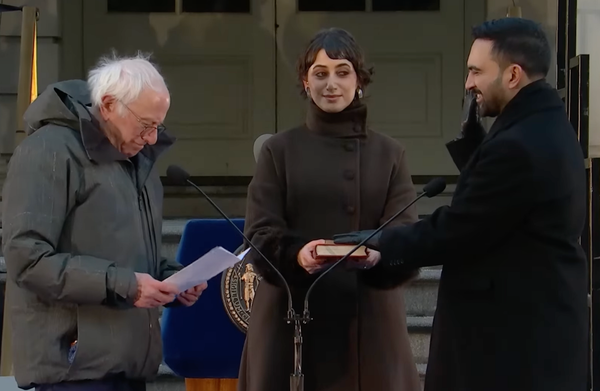

Teaching integrity

We are surrounded these days by stories of the basest, most egregious corruption: Tom Homan's Cava bag, $Trumpcoin, Bob Menendez' gold bars, Eric Adams' personnel decisions, and more, enough to put Verres to shame. Trump is out here saying that integrity is for suckers. Despite all that, and despite researching academic dishonesty for her entire decades-long career, Tricia Bertram Gallant remains adamant that most people want to be honest most of the time, and with a little forethought and prompting, they will.

My favorite part of Bertram Gallant and Rettinger's book was the chapter on teaching integrity itself. Teaching integrity should be the whole institution's responsibility, they write. Every staff member, every administrator, and every professor is responsible for helping students to grasp what it means to be honest, to earn credit for original work, and to give credit to others who helped. In a world of sophists, be a Socrates. In a world of electoral bribery, be Cato the Younger. (Maybe don't go that far – people really hated both of those guys at the time.) They suggest, for example, giving students ethics guidelines from a journal or association in your field and asking them how those guidelines would apply to their own coursework. Academics, as I mentioned in my last post, aren't immune to academic dishonesty by any means, and it's also an opportunity to learn language and strategies for articulating policies that will work.

If a professor wanted to model this behavior, it would probably be insufficient to just use citations and hope students learn the lesson implicitly. Instead, the professor would need to first draw the students' attention to the citation by, for example, explicitly narrating what they were doing and why: ”You'll notice that my data on this slide comes from X, Y, and Z. I tell you this because it is important for you to know that what I am conveying are not my own ideas but the ideas of others. This helps you verify what I am sharing and gives you sources to which you could go for more information. Citation is important in this way — it is a way for the writer (or presenter in this case) to implicitly converse with the reader (or listener). It's like saying, "These are the readings I found helpful for enhancing my knowledge, and you might find them helpful, too." Then, to help students retain the lesson and see themselves as capable of the behavior, the professor may have to give them a risk-free opportunity to practice citing their sources. Finally, to help students develop an intrinsic motivation to continue the behavior, the professor may want to talk about the values that undergird citation, such as honesty (being clear when I am using others' words or ideas) and respect (paying homage to those who came before us)." (The Opposite of Cheating)

Students would probably be happy to come up with examples of artists, influencers, or performers stealing each others' ideas too, to kickstart a discussion about academic integrity.

I recently learned that our colleagues who get Institutional Review Board approval for human subject research must go through a module on academic integrity to get certified, among other topics – I was able to register for it with my institutional sign-on, so you might be able to access this too. We should be doing a training on this in graduate proseminars. The one I took referred to the U.S. department of Health and Human Services' Office of Research Integrity Policy on Plagiarism (you might want to download that and save it, as they dispense with research integrity). Jim Lang also refers readers to the International Center for Academic Integrity for training resources and definitions. Bertram Gallant and Rettinger point to Mary Gentile's trainings on Giving Voice to Values.

Even in civ courses, you can look for opportunities to consider ethical questions with students, to build that muscle. At UNH, I taught in the Responsible Governance and Sustainable Citizenship Program, and we tried to foreground questions of ethics and citizenship in seminars. In "Individual and Society in the Ancient World," we talked about whether Agamemnon should have given Achilles everything he wanted, whether Antigone was a good role model for civil disobedience, and why people treated Philoctetes so hideously. (I think often of an embittered business student saying Antigone was acting crazy and no one in Greek tragedies made any sense.) I asked students: what different kinds of good leadership have you experienced? Would you rather be popular or intimidating? This is the kind of discussion I enjoy most in the classroom anyway. Any topic or text offers opportunities to discuss integrity and honesty, if you're looking for them. What could be more appropriate for a liberal arts education than helping students to grow a stronger conscience?

Recommended Reading

Ellen Delisio, Education World interview with Jason Stephens at UConn: "Enlisting Students to Create a Culture of Academic Integrity"

Ted Frick (University of Indiana Bloomington)'s online course for students: How to Recognize Plagiarism: Tutorials and Tests

Mary Gentile's trainings and curriculum on Giving Voice to Values -- there's also a Coursera course.

Miguel Roig (St. John's University)'s online course for the federal Office of Research Integrity, "Avoiding Plagiarism, Self-plagiarism, and Other Questionable Writing Practices: A Guide to Ethical Writing"

Gu, J., & Yan, Z. (2025). "Effects of GenAI Interventions on Student Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis." Journal of Educational Computing Research, 63(6), 1460-1492.

Tricia Bertram Gallant and David A Rettinger. 2025. The Opposite of Cheating : Teaching for Integrity in the Age of AI. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- from Bertram Gallant on the POD Listserv for educational developers:

- "if you'd like some easy-to-access concrete ideas, you can check out this site - https://sites.google.com/ucsd.edu/crafting-a-genai-and-ai-policy. Specifically in this section - https://sites.google.com/ucsd.edu/crafting-a-genai-and-ai-policy/documentation - there are worksheets/instructions you can use/adapt."

- "I wanted to make sure you were all aware of the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI) - https://academicintegrity.org - and in particular, its annual conference. This year it is in the fabulous city of Denver! Please check it out - https://academicintegrity.org/aws/ICAI/pt/sp/annual - and if you can, register to join us. It is an informative conference with kind people dedicated to teaching, learning and assessing with integrity. Fresh ideas, perennial advice, and amazing colleagues.If you have any questions about ICAI (I'm President Emeritus) or the conference, please don't hesitate to ask."

- "I wanted to make sure you all know about the amazing people we are featuring through our (informal) Podcast of the same name. People like Flower Darby, Tina Austin, Lew Ludwig, Laura Dumin, Christopher Ostro, Jeanne Beatrix Law, Joshua Eyler, Danny Liu, Jason Gulya, Mike Perkins, Leon Furze, Anna Mills, Phillip Dawson and more! The point of the podcast is to bring to life the ideas we present in the book to give educators, instructional designers, and other supporters of teaching/learning concrete examples of what can be done. You can view Season 1 and Season 2 episodes (aired weekly) here - https://www.theoppositeofcheating.com/blog/ - or listen on Spotify (https://open.spotify.com/show/5fhrnwUIWgFqZYBJWGIYml) or Apple (https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-opposite-of-cheating/id1829724960)."

Susan D. Blum, 2009. My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture. 1st ed. Cornell University Press.

James M. Lang, 2013. Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.