When Eulogies Turn Political: John McCain and Cato the Younger

Reactions to the death of John McCain over the last week have varied wildly, from adulation to anger. “Don’t speak ill of the dead,” some…

Reactions to the death of John McCain over the last week have varied wildly, from adulation to anger. “Don’t speak ill of the dead,” some say, criticizing McCain’s detractors for disrespecting the deceased man and his family. Now is not the time to bring up the things you didn’t like about him, or the things he did (or failed to do) that you think were politically problematic or harmful. On the other hand, we’ve also seen some eulogies for McCain that border on fiction.

But a lot of these reactions aren’t really about McCain. McCain stands in here as a metonym for an imagined bygone age of pre-Trump GOP politics. His passing feels symbolic of the passing of a political era. McCain served in the military with distinction, he didn’t demonize his political opponents, he wasn’t overtly racist or misogynist. He expressed his disagreements with the Trump administration publicly, and became a target for their derision and abuse. Praising McCain for these things is a way to criticize the current president.

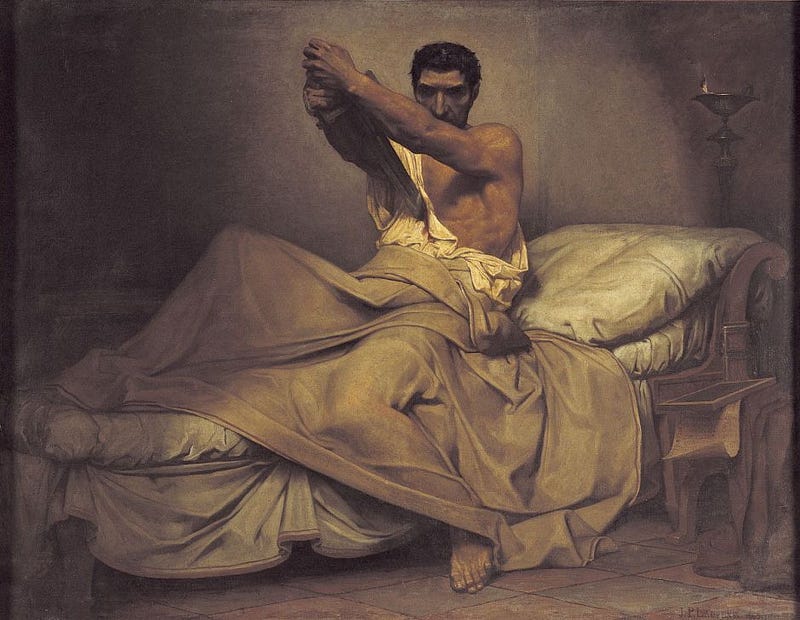

This dynamic, eulogy-turned-political-critique, reminds me of the ancient Roman Cato the Younger’s death in 46 BCE. Cato did not die of an illness; he committed suicide rather than live under the dictatorship of Julius Caesar. He supported Caesar’s rival Pompey in the civil war, and after Pompey was killed, he continued to lead a rebellious faction in North Africa until that faction was decisively defeated. Caesar would have pardoned him and allowed him to return to Rome and even to continue his political career, as he pardoned other enemies who surrendered to him, but Cato didn’t want to give him the satisfaction.

Cato is celebrated by ancient authors like Sallust, Plutarch, Valerius Maximus, Lucan, and even Vergil as a heroic defender of freedom who always spoke his mind, and who died rather than betray his principles. Later politicians followed Cato’s example and committed suicide when they could no longer live ethically under the reign of tyrannical emperors like Nero and Domitian. He had died along with popular government at Rome, and so his death served as a poetic symbol of the death of the republic.

The first eulogy of Cato was written by Cicero, Cato’s contemporary. The two were not exactly friends. When they had argued opposing sides of a legal case almost twenty years earlier, Cicero had poked fun at Cato’s rigid intransigence and obsession with esoteric Greek philosophical ideas. Cato resented the jokes, and disapproved of Cicero’s self-promoting tendencies. Cicero thought it was better to appease Caesar, to avoid provoking him, before the civil war; Cato publicly denounced Caesar and Pompey many times. After Cato’s suicide, Cicero wanted to write a fitting tribute to his colleague, but he also didn’t want to provoke Caesar’s wrath. “It’s a problem worthy of Archimedes,” he complained to his friend Atticus. “Even if I avoid talking about his public speeches or any proposal or advice he had about politics, if I praise his integrity and perseverance the way I want to, in a friendly way, they’ll hate hearing it. But he can’t be praised truly without elaborating on those things — he saw what was happening, and what would happen, and he tried to stop it, and he gave his life so that he wouldn’t have to see it happen” (Letters to Atticus 12.4.2). Cicero saw many friends lose their lives in the civil war, and he sometimes thought that they were the lucky ones, because they hadn’t had to live through the death of the republic.

Eventually, Cicero did publish a eulogy for Cato, and even Caesar said it was an impressive piece of work, although some readers think he was being sarcastic. Perhaps emboldened by Cicero’s success, Brutus — yes, the same Brutus who assassinated Caesar almost two years later, who was also Cato’s son-in-law and nephew — wrote an even more enthusiastic eulogy of Cato. A little too enthusiastic, Cicero thought. Brutus wanted to praise Cato’s career, his principled stand against Caesar, and his martyrdom, but in making Cato the hero of every story, he erased the contributions of Cato’s colleagues, including Cicero.

Brutus wrote admiringly about one of Cato’s first famous speeches: his speech arguing that the co-conspirators of Catiline, who had plotted to murder Cicero and overthrow the government in 63 BCE, should be executed without trial. Cicero was not only the target of the conspiracy but the consul who uncovered it and presided over the proceedings, and he felt that Brutus was taking credit away from him (and other senators who’d made the same proposal) in order to make Cato seem like the hero of this episode. “He is shamefully ignorant on this point: he thinks Cato gave the first speech about the sentence! In fact, everyone before him except Caesar had said the same thing. …Why, then, was there a vote on Cato’s proposal? Because he’d said the same thing, but with more impressive and numerous words. Brutus does praise me and the question I put to the senate, but not the evidence I discovered, the arguments I made, or what I’d determined myself before I consulted the senate. It was because Cato praised all that to the skies and thought it should be recorded that there even was a vote on his proposal” (Att. 12.21.1).

The temptation to lionize the recently deceased Cato, and to read into the symbolism of his past confrontations with Caesar, leads Brutus to stretch the truth. Brutus is telling a story from twenty years earlier, but it’s a story in which Caesar loses a political argument to Cato, and so it’s a story with new, increased significance under Caesar’s regime. The historian Sallust later wrote an account of the same episode, emphasizing the difference in personality and political outlook between them, which (unlike the eulogies by Cicero and Brutus) still survives today. Unfortunately, in his eagerness to praise Cato, Brutus ends up offending others. In his eagerness to praise Cato, he has gone so far that he’s actually rewriting history, and (incidentally) writing Cicero and other men still living out of the story. Cicero’s objection here is not to the idea that Cato gave a great speech, or to the idea that Cato was an admirable statesman. He’d written a eulogy himself to the same effect. But Cato hadn’t saved the day single-handedly, and had never even served as consul.

Caesar’s reaction to all this went a lot further than refusing to fly the flag half mast or attend a funeral. He wrote a rebuttal to the eulogies, an “Anti-Cato,” listing Cato’s personal flaws (alcoholism, a quick temper, a cold attitude toward friends and family, etc.) as well as criticizing his political career. Caesar also got one of his trusted lieutenants, Hirtius, to write another pamphlet criticizing Cato, which Cicero thought was hilariously amateurish and actually made Cato look better in the long run (Att. 12.40.3, 12.41.4). Worst of all, when Caesar had celebrated his unprecedented quadruple triumph in the months after Cato’s death, he had not only tastelessly celebrated his victory over fellow citizens in a civil war, but actually displayed paintings showing the deaths of Cato and other prominent leaders of the resistance. The historian Appian writes that the Roman citizens were too afraid of Caesar to complain, but could not help weeping at this tragic sight. It was not a good PR move for the dictator.

Cato’s death thus became the object of a rhetorical battle between Caesar’s regime and its critics, like McCain’s death. While it may be rude in general to politicize deaths (as the NRA often argues), these two deaths were political from the start, and politicized already by the dying. Cato probably wanted something like this to happen; his suicide was meant to send a powerful message, as a sort of political martyrdom for liberty. McCain, too, seems to have been very aware of the political import surrounding his death and funeral, and put a lot of thought into the symbolism of having Obama and W. deliver eulogies, while Trump was not even invited to attend. McCain also issued a “farewell statement” modeled (I think) on George Washington’s farewell address, in which he issued an exhortation to come together and have faith in traditional American values to get us through “challenging times.”

However, it’s one thing to commemorate leaders’ lives, or to be inspired to take political action in their memory; it’s another to revise history. Brutus wanted to celebrate his fallen comrade and father-in-law, but ended up offending the living. Likewise, Democrats praising McCain too effusively run a risk: in exalting McCain, they seem to be erasing the labor and values of their own allies and constituents. McCain criticized Trump, but so have others, and others have done more to translate their criticisms into action. McCain was not as overtly racist or misogynist as the president, but that does not make him a paragon of progressivism. Decency is admirable and may be disturbingly rare, but it is not the same as heroism. Praising the dead is understandable, especially when doing so makes a strong political statement, but it is easy to get carried away.