Metamorphoses 10: Orpheus the Misogynist

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

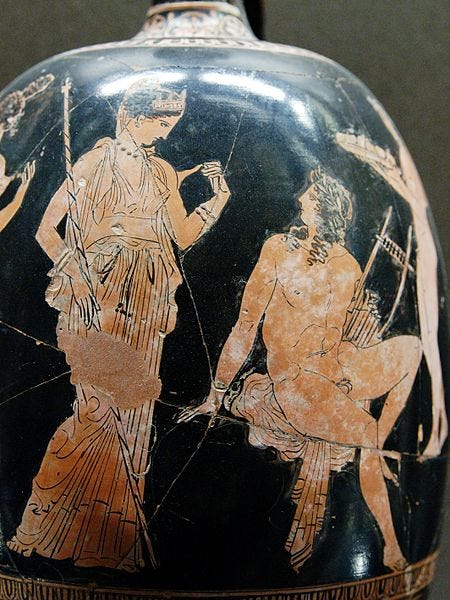

In Book 10, Ovid gives way to another poet, Orpheus. Orpheus’ story starts with a tragedy: the death of his beloved Eurydice, bitten by a poisonous snake at their fateful wedding. Orpheus handles his trauma by singing, and the theme of his complicated, nested series of songs is love of men, men loved and lost, and the rejection of women. He grieves and repudiates Eurydice all at once — surprising, since he loved her so much that he went all the way to the Underworld to get her back.

Through the phantom dwellers,

The buried ghosts, he passed, came to the king

Of that sad realm, and to Persephone,

His consort, and swept the strings, and chanted:

‘Gods of the world below the world, to whom

All of us mortals come, if I may speak

Without deceit, the simple truth is this:

…I came

For my wife’s sake, whose growing years were taken

By a snake’s venom. I wanted to be able

To bear this; I have tried to. Love has conquered;

This god is famous in the world above,

But here, I do not know. I think he may be,

Or is it all a lie, that ancient story

Of an old ravishment, and how he brought

The two of you together? By these places

All full of fear, by this immense confusion,

By this vast kingdom’s silences, I beg you,

Weave over Eurydice’s life, run through too soon.

To you we all, people and things, belong,

Sooner or later, to this single dwelling

All of us come, to our last home; you hold

Longest dominion over humankind.

She will come back again to be your subject,

After the ripeness of her years; I am asking

A loan and not a gift. If fate denies us

This privilege for my wife, one thing is certain:

I do not want to go back either; triumph

In the death of two.’ (10.13–43, Humphries translation)

The silver-tongued Orpheus appeals to Pluto and Proserpina as a couple united by Love (a euphemistic description of the events of Book 5), the same god who brought Eurydice to Orpheus, and as the powerful rulers of all humankind. He even offers to die himself. His song is so beautiful and moving that even the pitiless Furies start to cry, and the Underworld gods relent and bring Eurydice back to him. They warn him not to look back at her, but he can’t resist: “he, afraid that she might falter, eager to see her, / Looked back in love, and she was gone, in a moment” (56–7), and Eurydice dies a “double death.”

For seven days Orpheus sits by the river Styx, begging to go back to the Underworld, refusing to eat or bathe. Then he begins to wander around Thrace, and lives “without a woman / Either because marriage had meant misfortune / Or because he had made a promise” (78–80), choosing boys instead as romantic partners, and arguing that “That was the better way” for everyone else too (84). His songs are so beautiful that animals, both predators and prey, come to listen, and even the trees — including laurel and lotus, which originated with metamorphoses in the poem. The cypress comes too, and Ovid tells us how a boy named Cyparissus was turned into this tree by his lover, Apollo, in his wild grief for shooting his beloved pet stag.

Orpheus starts to sing about Jove’s love of the Trojan boy Gaynmede, and about another boy beloved by Apollo, Hyacinthus, accidentally killed by Apollo himself. As with Coronis and Leucothoe earlier in the poem, Apollo’s efforts as a healer are useless to help .

So, in a garden,

If one breaks off a violet or poppy

Or lilies, bristling with their yellow stamens,

And they droop over, and cannot raise their heds,

But look on earth, so sank the dying features,

The neck, its strength all gone, lolled on the shoulder.

‘Fallen before your time, O Hyacinthus,’

Apollo cried, ‘I see your wound, my crime:

You are my sorrow, my reproach; my hand

Has been your murderer. But how am I

To blame? Where is my guilt, except in playing

With you, in loving you? I cannot die

For you, or with you either; the law of Fate

Keeps us apart: it shall not! You will be

With me forever, and my songs and music

Will tell of you, and you will be reborn

As a new flower.’ (10.190–206)

Pederastic relationships between a man (or god) and a teenage boy were celebrated by some Greek writers, and were the subject of poems in Greek and Latin. But Ovid frames Orpheus’ homoerotic stories as a sort of escape from his grief for Eurydice. The accidental deaths of Cyparissus and Hyacinthus and the self-recriminations of Apollo echo Orpheus’ own loss of Eurydice, and perhaps his guilt over giving into the impulse to look back at her.

Then Orpheus’ songs take a turn away from boys, toward woman-hating. He mentions the women of Amathus, some of whom were turned by Venus into bulls for murdering guests, and the rest into stone:

The foul Propoetides would not acknowledge

Venus and her divinity, and her anger

Made whores of them, the first such women ever

To sell their bodies, and in shamelessness

They hardened, even their blood was hard, they could not

Blush any more; it was no transition, really,

From what they were to actual rock and stone. (10.236-42)

For the record, “whores” is Humphries’ editorializing (pro quo sua numinis ira / corpora cum fama primae vulgasse feruntur). In Orpheus’ song, the spectacle of these nasty women leads the sculptor Pygmalion to swear off women too.

One man, Pygmalion, who had seen these women

Leading their shameful lives, shocked at the vices

Nature has given the female disposition

Only too often, chose to live alone,

To have no woman in his bed. But meanwhile

He made, with marvelous art, an ivory statue,

As white as snow, and gave it greater beauty

Than any girl could have, and fell in love

With his own workmanship. The image seemed

That of a virgin, truly, almost living,

And willing, save that modesty prevented,

To take on movement. The best art, they say,

Is that which conceals art, and so Pygmalion

Marvels, and loves the body he has fashioned.

He would often move his hands to test and touch it,

Could this be flesh, or was it ivory only?

No, it could not be ivory. His kisses,

He fancies, she returns; he speaks to her,

Holds her, believes his fingers almost leave

An imprint on her limbs, and fears to bruise her. …

He decks her limbs with dresses, and her fingers

Wear rings which he puts on, and he brings a necklace,

And earrings, and a ribbon for her bosom,

And all of these things become her, but she seems

Even more lovely naked, and he spreads

A crimson coverlet for her to lie on,

Takes her to bed, puts a soft pillow under

Her head, as if she felt it, calls her Darling,

My darling love! (10.243–69)

I found this incredibly creepy, reminiscent of more recent tales of men in love with imaginary women, like Lars and the Real Girl and Her. There have been lots of adaptations of Pygmalion in later literature, perhaps most famously My Fair Lady, a movie I’ve loved since I was a kid. But now my reading of the Pygmalion myth is mediated by Madeline Miller’s chilling story “Galatea and Pygmalion” in the XO Orpheus collection of reimagined fairy tales. There is something very sinister about Pygmalion — and Orpheus — rejecting real women and then turning to a “perfect” fantasy woman with no voice and no autonomy. When Pygmalion goes to a festival of Venus and prays to meet a woman just like his ivory girl, Venus brings the statue itself to life, and Pygmalion gets to marry his ideal woman.

Nina McLaughlin’s take on Pygmalion’s wife puts a delightfully wry ending on the story:

“Time separated her from her statue life. “Smell this,” she’d say and lift her arm. We laughed! You got it, Ivory Girl! You stink! She sweat and seeped like the rest of us, less perfect every day. “There’s nothing duller than perfection.” She’d learned. “Really, it’s a myth.”’ (Wake, Siren)

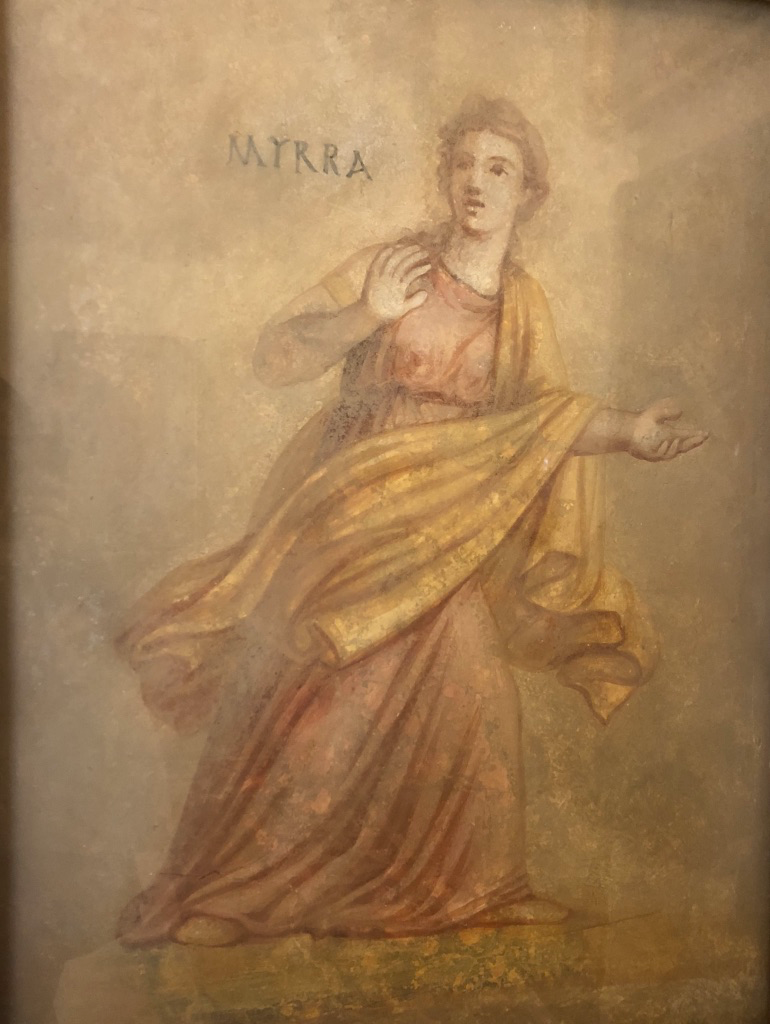

Pygmalion’s great-granddaughter Myrrha is up next in Orpheus’ song, and seems to confirm his generally bleak take on women. He warns us from the start that Myrrha is going to make her father Cinyras wish he had been childless, and that we might want to skip this part of the poem. Even Cupid disavowed any role in this accursed love story. Myrrha falls in love with her own father, and true to Ovidian precursors, gives herself a long talk about what to do. (I’m surprised Freud didn’t name a complex for her.) Tortured by incestuous dreams, she attempts to hang herself but is stopped by her nurse. The nurse, looking for a way to keep Myrrha alive, arranges to get the girl into her father’s bed without the father knowing who it is. When the time comes, Myrrha doesn’t want to go through with it, but the nurse persists — despite the ill-omened cry of the owl, who we know was once Ascalaphus, the sole witness of Persephone eating the pomegranate in the Underworld (Met. 5.539–50). Orpheus doesn’t shy away from describing any of this — there are lots of clever turns of phrase, Myrrha lamenting that her mother is “happy in her husband” and Cinyras having sex with a girl “young enough to be his daughter.”

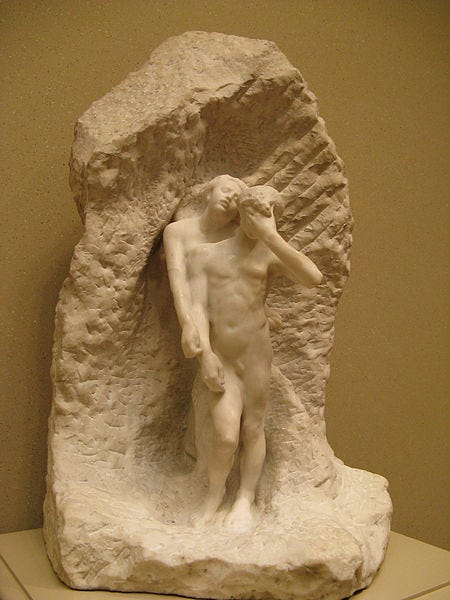

Myrrha gets pregnant and flees across the Arabian peninsula, and prays to the gods to punish her, allowing her neither life nor death. They turn her into the myrrh tree (I’ll never think of the gifts of the Magi the same way again) but her son is born from that tree, Adonis, the most beautiful of boys.

That little boy, whose sister

Became his mother, his grandfather’s son,

Is now a youth, and now a man, more handsome

Than he had ever been, exciting even

The goddess Venus, and thereby avenging

His mother’s passion. Cupid, it seems, was playing,

Quiver on shoulder, when he kissed his mother,

And one barb grazed her breast; she pushed him away,

But the would was deeper than she knew. Deceived,

Charmed by Adonis’ beauty, she cared no more

For Cythera’s shores nor Paphos’ sea-ringed island,

Nor Cnidos, where fish teem, nor high Amathus,

Rich in its precious ores. She stays away

Even from Heaven, Adonis is better than Heaven.

She is beside him always; she has always,

Before this time, preferred the shadowy places,

Preferred her ease, preferred to improve her beauty

By careful tending, but now, across the ridges,

Through woods, through rocky places thick with brambles,

She goes, more like Diana than Venus,

Bare-kneed and robes tucked up. (10.521–39)

If this is Myrrha’s revenge on Venus, was it Venus who made Myrrha pine for her father after all? (No tree pun intended.) It is poetic justice of a sort, because Venus’ transformation is reminiscent of Pygmalion’s sculpting of his ideal woman: Venus becomes someone else to appeal to her lover, letting her usual activities go and abandoning her usual favorite places. Instead of being passively adorned by her lover, she gives up her usual adornments, but she is still taking on the appearance her beloved desires. I have yet to find a painting or sculpture of Venus in huntress garb.

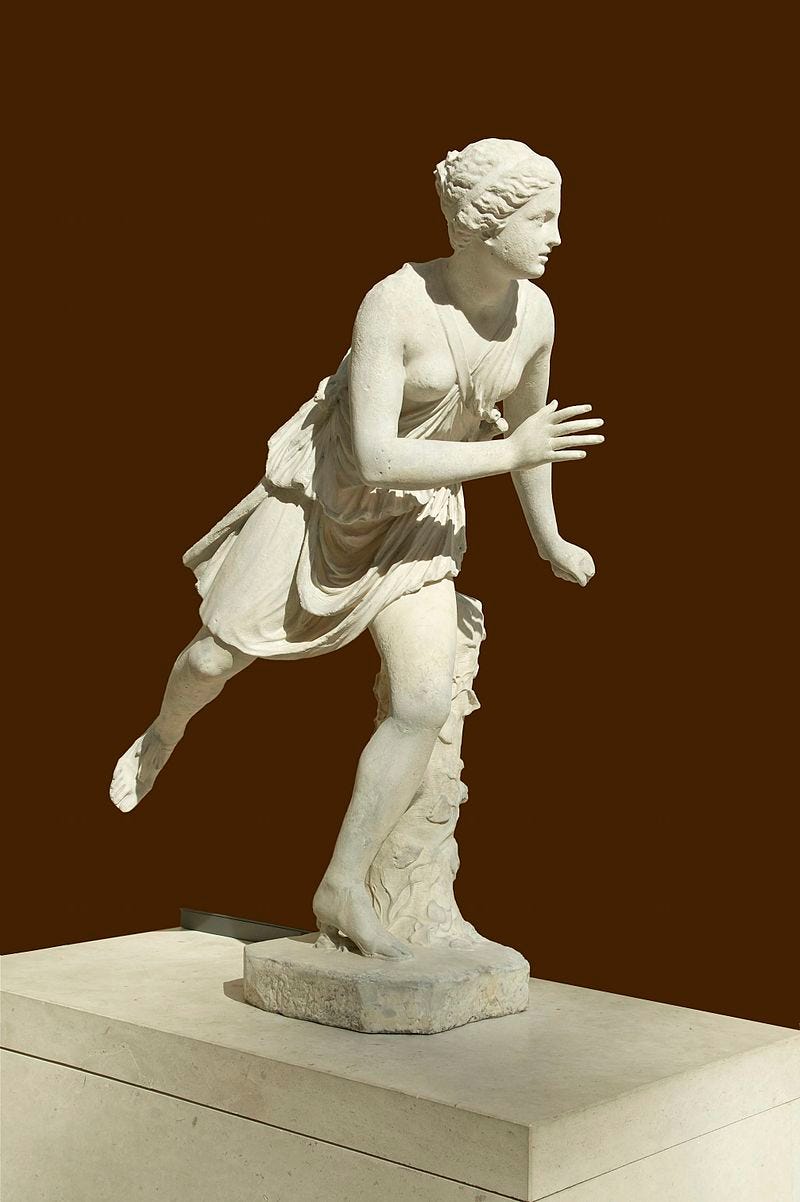

Venus is worried for Adonis’ safety in the woods, and urges him not to hunt anything as dangerous as lions, which she “hates and fears.” She explains why by telling Adonis the story of Atalanta, promising: “you will wonder at the way old crime / leads to monstrosities” (10.555–6).

‘She asked the oracle, one day, to give her

Advice on marriage. “You don’t need a husband,”

The god replied, “Avoid that habit! Still,

I know you will not: you will keep your life,

And lose yourself.” So Atalanta, frightened,

Lived in the shadowy woods, a single woman,

Harshly rejecting urgent throngs of suitors.

“No one gets me who cannot beat me running,

Race me!” she told them. “Wife and marriage-chamber

Go to the winner, but the slow ones get

The booby-prize of death. Those are my terms.”

The terms were harsh, but beauty has such power

That those harsh terms were met by many suitors,

Foolhardy fellows. Watching the cruel race,

Hippomenes had some remarks to make:

“Is any woman worth it? These young men

Strike me as very silly.” But when he saw her,

Her face, her body naked, with such beauty

As mine is, or as yours would be, Adonis,

If you were woman, he was struck with wonder,

Threw up his hands and cried: “I beg your pardon,

Young men, I judged you wrongly; I did not know

The value of the prize!”’ (10.562–84)

Atalanta is made to choose between killing men and losing herself. For her part, Atalanta doesn’t really want to kill anyone, or to race Hippomenes: “‘What god’ / She thought, ‘So hates the young and handsome / he wants to ruin this one, tempting him / To risk his precious life to marry me? / I do not think that I am worth it’” (10.611–15). Venus gives Hippomenes golden apples, to distract Atalanta long enough that Hippomenes can win the race and his bride. Hippomenes doesn’t thank Venus for her help, however, and so she turns the couple into a pair of lions, who she now fears will kill Adonis.

Venus’ protectiveness fails; Adonis ignores her advice and goes boar-hunting (following in Atalanta’s own footsteps from Book 8), and is killed, transformed into a flower by Venus as a monument to her love. With Adonis, Orpheus comes back to the theme of beloved boys with which he began, a boy who cannot be saved even by a god’s love. How else does this story connect to Orpheus’ song, aside from following Pygmalion’s family tree to its end? Maybe Venus’ love for Adonis is seen as forbidden or polluting, like Myrrha’s love for her father: Venus abandons her role as a goddess, enthralled by a mortal boy and a child of incest. Her comparison of Adonis to Atalanta feminizes her beloved, which Orpheus might have meant as pejorative.

Orpheus’ pederastic songs follow a well-established Greek tradition, but the framing of those songs as a rejection of women, a misogynistic turn after the loss of his wife, is bizarre. Many of Orpheus’ stories do describe accidental deaths that gods are powerless to stop, so they’re more relevant to Eurydice than he might mean them to be. He centers his stories on Pygmalion, whose (unnatural) wish is granted by Venus but whose descendants torment and are tormented by Venus; not a positive take on romantic love. It seems like Orpheus, like most people, finds a strange way of processing his grief.