Metamorphoses 9: Love hurts

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

A blog about teaching Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a classical mythology course

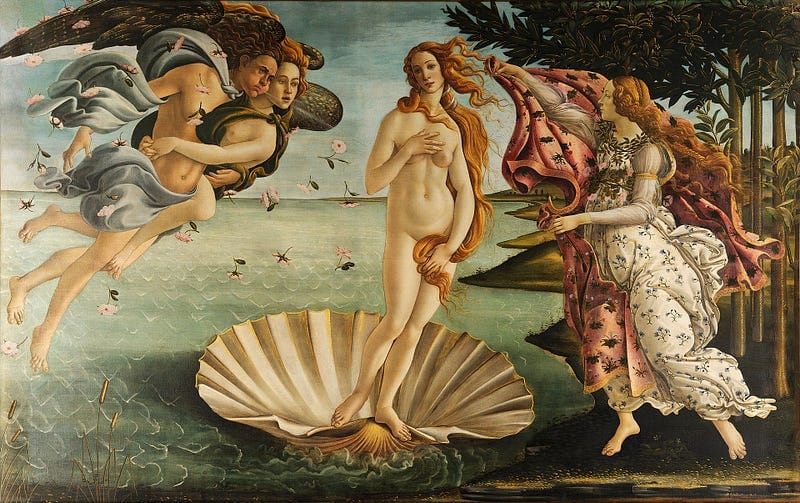

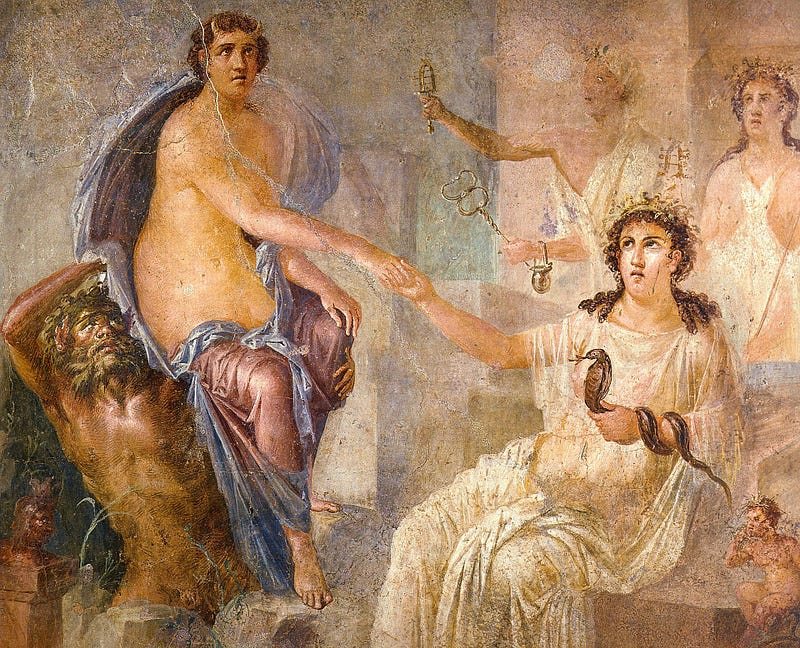

This week, in lieu of a field trip we had planned, I asked my students to do a virtual scavenger hunt, finding and comparing images of the god or hero of their choice. I was a little surprised at how many of them chose Aphrodite/Venus — several used photos they’d taken on trips to Florence of Botticelli’s painting. I once visited a second-grade classroom where one of my students was teaching a lesson on classical mythology, and they liked drawing symbols related to Aphrodite too, maybe because it was just like making Valentines. In our culture, a goddess of love might seem sweet and cute, but in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Venus causes immense suffering. She and her mischievous son Cupid prove their power over gods and humans alike by afflicting them with painfully powerful desires that burn like fire. People fall in love with people they can’t have, gods fall in love with mortals who don’t want them, lovers kill or torment their rivals. Even Botticelli’s painting of the “Birth of Venus” only tells the pretty part of the story, leaving out Aphrodite’s genesis from the blood and foam left over from the castration of Ouranos (Heaven), according to Hesiod’s Theogony.

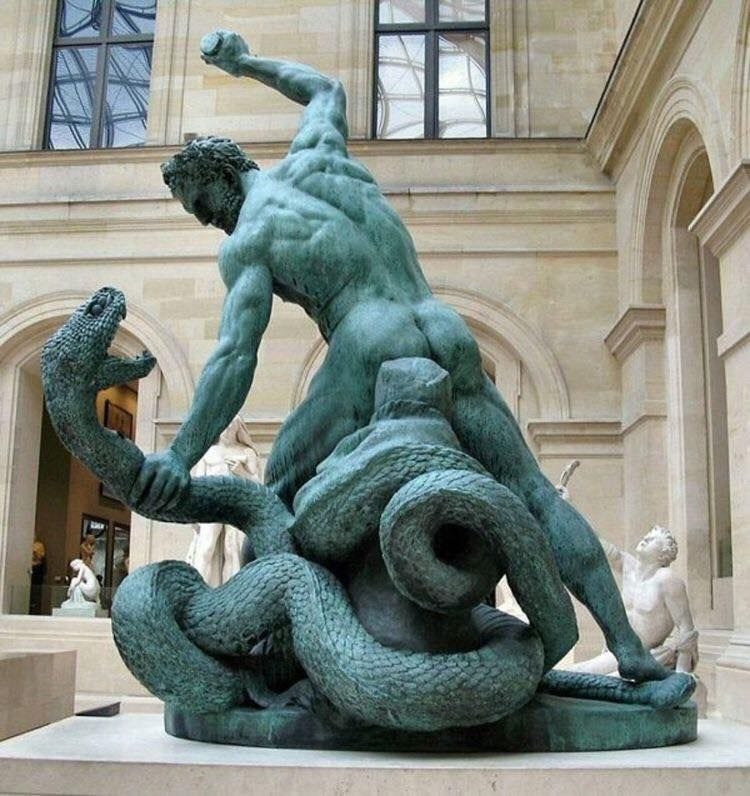

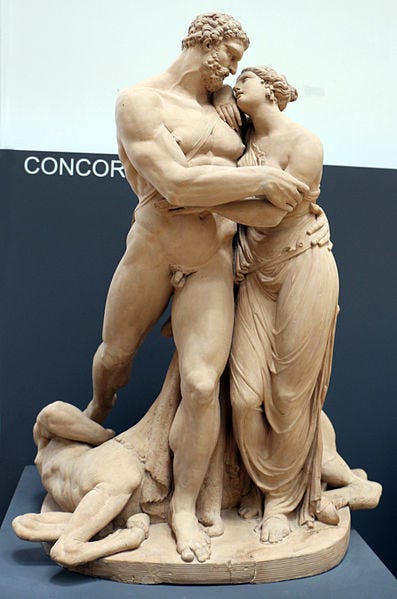

Book 9 reaches new heights of anguish and even torture, all caused by love, many centering around Hercules. Ovid has been tracing “history” from the creation of the world down to his own day, but he’s been pretty coy about how Hercules fits into that chronology. Ovid has skipped over his birth, his madness and murder of his wife and children (left out of the Disney movie too), and the famous Twelve Labors he did in penance. To be fair, the mythology of Hercules is so vast that it could have taken up many epics by itself. Now, we hear from the river god Achelous how Hercules married his second wife, Deianira. He and Achelous had a wrestling contest, with Deianira as the prize, and although Achelous transformed into a serpent and then a bull, Hercules wrestled him to the ground and even broke off one of his horns.

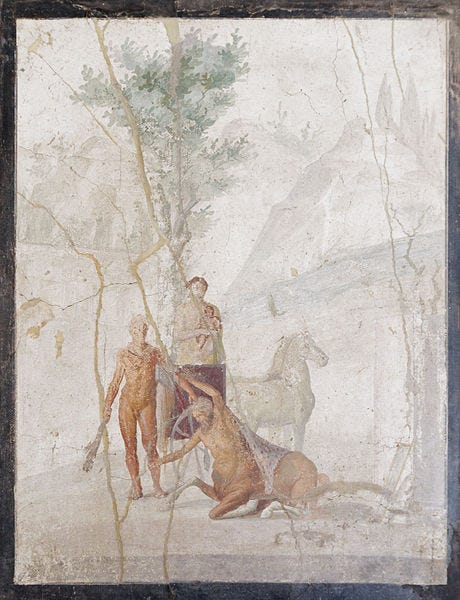

Hercules carries off his bride, but comes to a river too wide for him to cross with her. The centaur Nessus helpfully offers to carry Deianira for him (what did she think of that arrangement?), but then tries to run off with her. Hercules shoots him with an arrow, poisoned with the venom of the Hydra, and reclaims his bride.

As he dies, though, Nessus gives his robe, soaked in poison and blood, to Deianira; in Sophocles’ tragedy Trachiniae, he tells her that it will keep Hercules from ever loving another woman besides her. Ovid’s Nessus calls the robe an “inritamen amoris,” which Deianira takes to mean “love charm,” as in something that will rekindle feelings of love. It turns out to mean something different: Deianira literally sets her beloved on fire.

Wicked Rumor comes to Deianira while Hercules is off sacking the city of Oechalia: he has fallen in love with someone else, she hears, a woman named Iole. Just like Procne, Medea, or Scylla, Deianira has a conversation with herself about what to do next.

She loves him, she believes it, she is frightened,

Gives way, at first, to tears, pities herself,

Makes her grief grow by weeping, and recovers

A little, thinking: ‘What’s the good of weeping?

Tears would delight my rival, and she is coming,

Is on her way: what I had better do

Is hurry, figure out something, while I can,

Before she is in my bed. Shall I complain,

Shall I keep silent? Shall I go again

To Calydon, or linger here? Shall I

Forsake this house, or keep her out? I might

Remember Meleager was my brother,

Might plan some desperate deed, murder my rival

To show her what a woman in grief and outrage

Can do by way of vengeance.’ So her mind

Wavers in all directions, but at last

She thinks it best to send the robe of Nessus,

Dyed with his blood, to help to make her love him. (9.143–54, Humphries translation)

I think Humphries mistranslates this last part: Deianira gives the robe to Hercules “to give forsaken love its strength back” or “to give power back to a defeated love,” i.e. Nessus (quae vires defecto reddat amori). To be fair, it’s very hard to come up with a single English phrase with the ambiguity of the Latin one. Nessus’ words are like an oracle in a classic tragedy, holding a double meaning that isn’t clear until the prophecy has come to pass. In Ovid’s version, it’s Deianira’s fear, her misguided love for Hercules and jealousy of a rival who is only imagined, that leads to a tragic outcome. In deciding not to kill Iole, she ends up choosing a course of action that will kill the man she loves. Deianira is, after all, the sister of Meleager, the hero burned alive by their grieving mother Althaea in the previous book.

When Hercules puts the robe on, the hydra’s poison burns his skin like some kind of horrific acid, boiling his blood and eating into his marrow. He assumes he has been attacked not by his wife but by an enemy and goes running and stumbling through the countryside to Oeta, calling out:

‘Gloat on my suffering, gloat, O cruel Juno,

Sate that relentless heart, watching me burn!

Or if an enemy — and I am yours,

That much is certain — could find some reason

For pity, take away this life of mine,

Sick from its torture, hateful, born for anguish. …

Centaurs could not resist me, nor the boar

That ravaged Arcady. I slew the Hydra

That gained by its own loss, and little good

That did the monster! And the Thracian horses,

Fed fat on human blood, the mangers filled

With human bodies, I found, and when I found them

Tore them to pieces. These were the hands that choked

The lion of Nemea, these the shoulders

That held the weight of the world, one time, for Atlas.

Juno grew tired of giving orders; I

Was never tired obeying them. But now

A new doom comes upon me, one I cannot

Fight off by arms or courage, and the fire

Devours my lungs, and feeds on all my members.

But still Eurystheus keeps his health: who is there

To think that gods exist?’ (9.174–204)

Hercules builds himself a funeral pyre and chooses death, and his mortal side burns away, leaving only his semidivine spirit to transform fully into a god — like a serpent shedding its old skin, Ovid says. The hero who doubted the existence of any gods turns into one. All of his trials and labors and suffering on earth have earned him immortality. He becomes a sort of hero to Stoic philosophers as a representation of virtuous endurance, and a forerunner to the Roman heroes who will undergo apotheosis later in the poem — maybe even to Ovid himself, whose suffering in exile will result in an immortal work of literature.

Hercules’ extended family hasn’t been any luckier in love. His mother Alcmena grieves for him with Iole, who has married his son Hyllus by this point and is pregnant. Alcmena recalls that Juno, jealous of her for bearing Jove’s child (unwillingly), prevented her from giving birth to Hercules so that she was in labor for seven days. The maid who eventually tricked the goddess of childbirth into relenting, Galanthis, was turned into a weasel herself for helping Alcmena. Iole then tells the story of her sister, Dryope, who was turned into a tree for picking the berries of the lotus, which itself used to be a nymph until she was pursued by Priapus and transformed to escape him. Dryope, like Hercules, calls out the injustice of her fate, and she worries for her infant son:

‘If the unhappy

Can ever be believed, I swear by the gods,

I have not earned this evil; I am punished

Without a crime; my life is innocent,

Has always been: if I am lying, let me

Lose all my leaves, be lopped with axes, burned

In fire forever. Take my boy away

From the branches of his mother, find a nurse

And let him drink his milk under my tree,

Play here, and when he learns to talk, then teach him

To say in sorrow: Here my mother hides.

But let him fear the ponds, and pick no flowers,

And let him think that all the bushes are

Bodies of goddesses.’ (9.369-82)

With the end of Iole’s story, we return briefly to King Minos in Crete, now an old man, and a new challenger, Miletus. Miletus’ daughter Byblis is a sort of literary double for Scylla, who had fallen in love with Minos at the start of Book 8. Like Scylla, Byblis suffers from forbidden love, not for an enemy but for her own brother, Caunus. Like Scylla, she talks herself into thinking that maybe this love isn’t so bad after all, that she should pursue her beloved. Byblis is conscious that she is arguing like a sophist with herself, a clever rhetorician who can make a bad idea sound good with arguments from precedent.

‘All we have

By way of common bond is common barrier.

What do my visions mean then? And what weight

Have dreams? Do they have any? It is better

For the gods, it seems; the gods had their sisters,

Saturn had Ops, and Ocean Tethys, Jove

Took Juno; gods are laws unto themselves,

And who am I, to strain poor human customs

To superhuman license? I must either

Drive this forbidden flame out of my heart

Or, if I cannot, die, and as I lie there,

Dead on my bed, my brother will come and kiss me.

What I would like needs two for consummation:

Suppose it pleases me, but seems a crime

To Caunus? But the sons of Aeolus

Were not afraid to enter their sisters’ chambers.

Where did I learn of them? Why have I given

Myself such precedents? What am I doing?

Be gone, disgusting flames, and let him never

Love me, except as brother should love sister!’ (9.495–510)

Byblis, like Hercules, is on fire, and is ready to die if it will extinguish the flames. Like Deianira, she decides to take a less drastic course and appeals to her beloved, invoking Venus and Cupid as her instigators. Caunus is (justifiably) horrified, and in her grief over this rejection, Byblis curses herself for being so rash, and for not appealing to Caunus in person: “his mother was no tigress,” she recognizes, recalling Scylla’s accusation of Minos. Like Scylla, Byblis is condemned to wander by herself until she is transformed, not into a bird but into a fountain, still weeping.

But after all these stories of unrequited and transgressive and tragic love, at the end of Book 9, we get a surprising story with a happy ending. Ligdus and Telethusa, a poor couple in Crete, are about to have a baby, but Ligdus doesn’t want to let the baby live if it’s a daughter — he doesn’t want the expense of a bride’s dowry. Telethusa prays to Isis, described here as a new guise of Io, whose suffering and transformation we saw in Book 1. Isis tells Telethusa to have faith and to raise the baby as male, which she does, when her daughter Iphis (an androgynous name) is born. Iphis grows up disguised as a man and is betrothed to a woman, Ianthe, and falls in love with her, but worries about what will happen when they get married. Iphis feels that there is something wrong with her, because she loves Ianthe. Born on Crete, Iphis looks to Pasiphae for a comparison in forbidden love, and wonders if Daedalus himself could contrive a solution to their problem.

The mother took the fillets off, her own,

Her daughter’s, and, with flowing locks, was praying

Before the altar: ‘O Egyptian Isis,

Dweller by the seven-horned Nile, bring help, I beg you,

Heal our anxieties! I can remember

Your symbols in my dreams, the clashing sounds,

The holy rattles, the votaries, the torches,

And I was careful to obey those orders.

That Iphis still beholds the light, that I

Was never punished, that is all your doing,

Your wisdom and your gift. Pity us, help us,

The two of us, in our need.’ And as she wept,

The goddess seemed to move, the altar trembled,

The doors of the temple shook, the moon-shaped horns

Were darting light, and the noisy rattle sounded.

The mother left the temple, cheered a little,

If not entirely reassured, and Iphis

Was walking, in her usual way, beside her

But taking, somehow, longer steps than usual,

With face not quite as shining, and she looked stronger,

The features not as soft, and the hair shorter,

The vigor less becoming to a woman.

She was no woman now, but a bridegroom!

Bring offerings to the temples, bring them quickly,

Rejoice, be unafraid! (9.771–92)

Everyone in this story, remarkably, gets what they want: Telethusa gets a child, Ligdus gets a son, Iphis gets to marry Ianthe, Ianthe gets to marry Iphis. This metamorphosis is what Iphis wishes for, not in a moment of panic or to get away from a violent threat, but to live the life they choose. Although it is Venus whom Iphis blames for their problem, it is Isis who solves the problem. Io has become a benevolent goddess who watches carefully over her favorites. It’s a real contrast to most of the love stories in the poem, especially in Book 9. I don’t want to romanticize this too much or make Ovid out to be LGBTQ-friendly when he isn’t particularly, but I found this myth to be a refreshingly joyful interlude.

Another image that stuck with me this week was Dryope’s warning for her son: “But let him fear the ponds, and pick no flowers, / And let him think that all the bushes are / Bodies of goddesses.” Minos, Pasiphae, Daedalus, and Ixion’s children recur from Book 8 to Book 9, and Io returns from Book 1. Ovid has populated his whole mythological world. Now, when a bird flies overhead or a tree is mentioned in passing, we often know an Ovidian story behind it. Family patterns (genealogical and thematic) and local histories start to become clearer, but the poem is still a fantasy world where the natural landscape is alive with its own history too.